The criminalization of men and women prisoners is linked to these individuals’ socially constructed gender roles.[1] Gender is deeply internalized by both males and females starting at a young age. For example, girls’ behaviors are highly supervised and strictly controlled, while boys are taught to be independent, tough and aggressive.[2] Gendered behaviors play a fundamental part in constructing prisoners’ identities—both in the circumstances that led to their incarceration and in their management and response to the control exercised over them in corrections facilities. The woman prisoner’s identity is constructed as denial of femininity; in a broadly received view of the character of female criminality, all women prisoners are frustrated by an oppressive, patriarchal culture and thus are alike. When a woman commits a crime, she challenges her socially mandated passivity and therefore must be penalized. In contrast to the woman prisoner who resists her societal role, however—in this same paradigm of gendered criminality—the male prisoner utterly embodies the image of hyper-masculinity. According to the Bureau of Justice, the majority of crimes men commit are violent.[3] “Doing gender,” a concept introduced by sociologists Candace West and Don Zimmerman in 1987, identifies the way in which expressing masculinity is directly linked to criminal behavior, especially the use of violence.[4] The violent nature of crimes understood as characteristically male frames how the male convict enacts his learned role. Thus, the male prisoner’s identity is constructed by compulsive masculinity. Moreover, the prison environment reinforces the gender binary by emphasizing the virtues of traditional femininity and masculinity. Therefore, the ways which men and women are socialized and the gendered order of the prison system co-create prisoners’ identities from the gender studies perspective.

The notion that women are biologically inferior to men is deeply embedded in the American social practice and ideology. Society functions according to this underlying binary, and as a result, women are positioned at the margins of longstanding patriarchy. Since women do not exercise the same level of agency as their male counterparts, they are continually limited to roles a gender-obsessed society expects them to perform. In the late nineteenth century, for instance, the cult of domesticity reigned over American culture.[5] A married woman was effectively her husband’s property, a large majority of women were not educated, and women’s participation in the public workforce was limited. The primary roles of the woman were to be homemakers and caretakers for their husbands and children. And although the domestic lifestyle was extremely restrictive and frustrating for many women, most of them chose to remain submissive. However, some women rebelled. Those who did not conform to the traditional notions of femininity were sometimes locked up behind prison bars. Many women prisoners were convicted of killing their husbands or other men when they finally proved unwilling to tolerate abusive relationships any longer. A good example of this is the case of Hattie La Pierre, who met an alcoholic gambler, Harry Black in Denver in 1905.[6] The two moved to Wyoming where their relationship became one of consistent physical abuse. Hattie refused to file charges even when her abuse became public knowledge, often fearing for her life. Finally, when Black dragged Hattie into the street about to beat her, she opened fire, killing Black. Hattie spent three years in the Wyoming State Penitentiary for manslaughter. The judge who sentenced her neglected to consider her violence as committed in self-defense.[7]

Gender and social deviance

The gender-grounded belief structure according to which women have been incarcerated has not changed since the nineteenth century. When a woman entered the historical legal system, she was transformed from “respectable female into a social deviant” in earlier periods.[8] Some things have remained unchanged. Although the crimes that lawmakers consider worthy of punishment by the state are different in the early twenty-first century, the criminalization of women remains constructed along nineteenth-century lines. For example, in the nineteenth century when abortion was still illegal, women who solicited or performed illegal abortions were incarcerated. In 1873, Canon City’s first woman inmate, Mary Solander, was convicted of manslaughter, a death supposedly caused by an abortion gone awry.[9] Prior to her arrest, Mary lived in Boulder, Colorado with her husband and four children. She was well-respected by other Boulder residents as the first woman doctor in the area, and regularly advertised her practice in the Boulder County News. However, despite Solander’s professional success, male doctors performed most abortions at this time, rendering a woman’s medical practice transgressive within the context of cultural norms.

Solander’s case began when Mr. Clement Knau approached her seeking an abortion for his mistress, Mrs. Fredericka Baunn. She died during the procedure. Authorities concluded that the powders Solander used to sedate Baunn were the cause of her death, and that Solander had attempted to dispose of the evidence by discarding the fetus in a river. Solander was then sentenced to three years in the Cañon City Prison even though Knau was pardoned. Solander’s conviction, for which she was harshly punished, and Knau’s role in the tragedy, contrastingly dismissed, are telling instances of how gender defined criminality in the period. Solander embodied the non-feminine and savage role of the woman criminal. As a woman doctor, Solander defied traditional femininity, so the prosecution for murder served as a punishment for challenging social norms. Thus, women’s lesser status served as the basis on which society viewed and treated women prisoners.

Recent cases emphasize how women are still prosecuted and sentenced for gendered crimes today. American society does not allow women to express feelings of frustration and rage against gendered oppression, and relegates those who do as mentally insane. The case of Casey Anthony highlights this practice. In 2008, Anthony was charged with aggravated manslaughter of her two-year-old daughter, Caylee.[10] When Anthony testified against these allegations, expressing her anger and frustration, media reports depicted her as crazy, stating that she lived in a “completely narcissistic world” and that her daughter’s disappearance “was all a big game to her.”[11] Murder charges against Anthony were eventually dropped in 2011, but even after she was found not guilty, the general public continued to criminalize her, claiming that she was mentally unstable.

Judith Scheffler’s Wall Tappings provides a lens that explains how Casey Anthony’s case demonstrates how women prisoners defy social norms. According to Scheffler, the woman prisoner today has a history of physical or sexual abuse and is usually a mother. This identity is consistent with Anthony’s case, as “allegations of incestuous sexual abuse by both her brother and her father would become the centerpiece of her criminal defense.”[12] Further, the way the media and judicial officials treated Anthony demonstrates how “that is how they deal with a woman; she is accused of doing something so stupid that they defy belief. Then, if a woman is courageous or if she grasps some bit of knowledge easily, men claim that she is only a ‘pathological’ case.”[13] Since prosecutors often rule that expressions of rage are not inside the realm of the normal woman’s experience, women who show these emotions must—according to the logic of a rigidly gendered system—be crazy. Therefore, both Solander and Anthony’s cases, although decades apart, describe a continuity of women’s gendered limitation as both the trigger and account for their criminality.

Under normal circumstances, a woman is already deprived by her gendered status as secondary, but the woman prisoner’s criminal status positions her at an even greater disadvantage within society. The female offender’s identity is located at the intersection of woman and criminal. These two subordinate categories work together to undercut women prisoners’ safety and rehabilitation. Women prisoners’ identity is highly stigmatized, while offenders’ subjectivity diminished in an attempt to dehumanize and justify mistreatment. The woman prisoner’s identity is oppressed twofold; she completely loses her subject status. Women prisoners of color are positioned even lower in society than white counterparts because their racial identity acts as further oppression.

Abortion remains a touchstone for explaining the social response to the intersection of gender and criminalization. Mary Solander’s conviction for performing an illegal abortion provokes exploration of the valence of history in the current abortion debate and its effects on women. Abortion rights serve as a tool of agency for women, yet historically men have exercised enormous power over women’s bodies through controlling their sexuality and reproduction. Not until 1973, in the Supreme Court Case Roe v. Wade, were women granted the right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. Although abortion is now legalized, it is still an issue at the forefront of political debate and continues to divide parties. Pro-life politicians sustain control over a woman’s ability to exercise social agency by advocating for fetal rights. Pro-choice politicians counter these arguments by advocating for women’s natural rights. The abortion debate is part of a larger issue, a movement that addresses all of the conditions of women’s liberation. Women earn less than men, they are subjected to sexual violence, they have little or no access to publicly provided day care, and they have less familial or political decision-making power than men, but in the nineteenth century, women’s ability to employ agency was still more limited than it is today. Consequently, the punishment for abortion was more extreme in the pre-Roe period, when women who got abortions were sent to prison. Although a woman cannot be incarcerated for getting an abortion today, however, public discourse still stigmatizes her. In a sense, women continue to be criminalized for getting abortions.

Female experience in prison

Just as patriarchal forces still constrain women in receiving abortions, they also follow women inmates inside of prisons. Before the emergence of separate women’s correctional institutions, the gender disadvantages already faced by women within society sometimes erupted into intense physical and mental violence when they become prisoners. Hence, the woman prisoner’s experience in custody is rooted in violence. During the early years of the Cañon City prison, the abuse women suffered in the outside world continued within the correctional facility. Women endured overcrowded conditions, a lack of sanitation, and rape. They were not provided with rehabilitation programs, health care, or pregnancy care.[14] In a 1909 report to a Texas penitentiary investigating committee, inmates Rosa Brewing and Hannah Steele testified to the lack of care given their fellow inmate, whom they referred to as Elvira.[15] Elvira, who went into labor in the morning, was told to resume her job on the farm. The inmate delivered her child under a tree and did not receive medical attention until the late evening, when the infant had already died of pneumonia.[16] Although pregnancy care varies by state and institution, this did not appear to be extraordinary for the time. Today in Colorado, there remains inadequate prenatal care or preexisting arrangement for delivery for incarcerated pregnant women.[17]

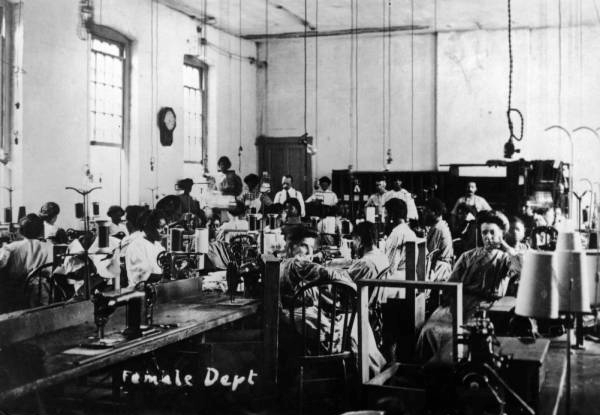

The penal system reestablishes the social order of gender roles for prisoners as its broad historical development demonstrates. The emergence of separate women’s prisons serves as a powerful example. Authorities first began to house woman inmates separate from men in the late nineteenth century. The first women’s prison, the Indiana Reformatory Institute for Women and Girls, was established in 1873 by Quakers Rhoda Coffin and Sarah Smith.[18] This pioneering institution’s goal was to reintegrate prisoners into Victorian gender roles. Reformists aimed to rehabilitate women prisoners by training them to be good mothers, wives, and educators. Prisoners were given work along the lines of standard “woman’s work.” Women prisoners assumed the duties and responsibilities they had at home such as cooking, cleaning, sewing, typing, laundry, and working in the beauty salon. The public’s response to the institution was extremely positive. Coffin and Smith were greatly celebrated, as their new institution was perceived to have had “rescued women from sexual abuse in an institution full of predatory guards and prisoners.”[19] However, it would later be discovered that Smith humiliated, assaulted, and dunked prisoners who didn’t follow the rules. The treatment of women prisoners in separate institutions, even in this reformist experiment, thus demonstrates how the prison system reinforced the nineteenth-century gender binary.

While the woman prisoner defies gender roles, the man prisoner typically capitulates to them. Expressions of masculinity are the link to criminal behavior in men. From early childhood and throughout adolescence, society teaches boys to have no mercy, and to strive to behave like “real men.” This socialization, starting from birth, contributes to the disproportionate number of men committing violent crimes and entering the criminal justice system. These individuals’ physical aggression often continues in penal institutions. Compelling examples emerge from the records of Colorado correctional facilities. In 1990, Cañon City inmate Murphy Miles Jr. assaulted four prison guards.[20] In 1999, inmate Johnny Estrada was found guilty of second-degree assault of inmate Michael A. Garcia.[21] These instances are only a few of the many instances of the gendered violence endemic in correctional facilities for male offenders.

While women inmates are forced to regain their femininity in prison, their male counterparts typically attempt to maintain their masculinity. Internalized notions of masculinity dominate the prison culture. The difference between men’s and women’s gendered behaviors and the social response it is accorded are shaped by the belief that a man’s identity changes when he enters prison. In The Society of Captives, sociologist Gresham Sykes analyzed prison culture of the 1950s in order to provide explanation for the character of gendered prison relationships. The world outside prison walls—the world of women, as Sykes interpreted it—gives the male world meaning in its inherent contrast of male-male interactions.[22] Men construct their identities as distinct and opposite to women. The classification of sex and gender as disconnected forms of masculine and feminine define a man’s experience within free society. However, in prison, the gender binary no longer maintains. In this new, all-male environment, men are forced to adopt new methods of constructing their gendered identities. Consequently, prison culture pressures men to prove their true manhood. Common masculine traits such as toughness and dominance, prerequisities to a strong masculine reputation, are achieved by exerting physical and moral strength over other inmates and guards. Sykes notes that, “the real man is prisoner who ‘pulls his own time. . ., [can maintain] his integrity. . ., [can] stop himself from sriking back at the custodians. . . .”[23]

Gender roles integral to both wider society and prison culture have continued to construct prisoners’ identities from the late nineteenth century until now. In order to preserve the “natural” order of things, women must be passive, maintain strong interpersonal relationships, and never express feelings of rage both in prison and outside. Those empowered by society feel threatened when a woman exercises her agency. Women who commit crimes as the result of their frustration due to the limits of traditional femininity find themselves locked up behind bars. Thus, women achieve criminal status by deviating from societal standards. Further, the prison system reestablishes order by institutionalizing gender norms. Women inmates must learn how to properly behave like socially acceptable women so that once they are released from prison they will not disrupt the status quo.

On the other hand, men are incarcerated for enacting extreme aggression and dominance. These masculine qualities manifest as violent actions, so most crimes committed by men are violent crimes. Like women prisoners, men prisoners cannot escape gender roles once they go behind bars. Prison culture disenables men to develop alternative, non-violent identities, and as a result, men prisoners portray conventional masculinity in order to prove their manhood. As a result, the penal system little changed in regard to gender since the later nineteenth-century origin of the Cañon City complex leaves inmates of both sexes disempowered, confined by a social system as rigid and impenetrable as prison walls.

[1] Originally researched and drafted by Payton Katich.

[2] Anne M. Butler, Gendered Justice in the American West (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 16.

[3] U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, “Special Report: Women Offenders,” ed. Lawrence A. Greenfeld and Tracy L. Snell (1999), 1.

[4] Jessie L. Krienert. “Masculinity and Crime: A Quantitative Exploration of Messerschmidt’s Hypothesis,” Electronic Journal of Sociology (2003). http://www.sociology.org/content/vol7.2/01_krienert.html.

[5] Kathleen Connellan, “Cult of Domesticity,” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies (Hoboken: John M. Wiley, 2016).

[6] Butler, 123.

[7] Ibid., 124.

[8] Ibid., 26.

[9] Elinor Myers McGinn, Female Felons: Colorado’s Nineteenth Century Inmates, (Cañon City: Freemont-Custer Historical Society, 2001), 3-7.

[10] Diane Diamond, “Casey’s Roommate Tells All,” Daily Beast, June 22, 2011, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2011/06/22/casey-s-rommate-tells-all.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Judith A. Scheffler, ed., introduction to Wall Tappings: An International Anthology of Women’s Prison Writings, 200 to the Present (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986), xxvi.

[14] Butler, 149.

[15] Ibid., 167.

[16] Ibid., 168.

[17] National Women’s Law Center, The Rebecca Project for Human Rights, “Mothers Behind Bars,” October 16, 2010, http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/mothersbehindbars2010.pdf.

[18] Rebecca Onion, “Inmates at America’s oldest women’s prison are writing a history of it – and exploding the myth of its benevolent founders,” Slate, March 22, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2015/03/indiana_women_s_prison_a_revisionist_history.html.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Unattributed fragment, undated, Royal Gorge Regional Museum (hereafter RGRM), “Prison inmate” folder.

[21] RGRM, “Prison inmate” folder.

[22] Gresham M. Sykes. The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 71-72.

[23] Sykes, Society of Captives, 102.