The social system within Cañon City’s prisons is framed by unique norms and beliefs at once separating it from and reflecting wider American culture.[1] Humans are social beings and the formation of ties among inmates is inevitable. The character of social bonds is dependent on the conditions in which they are established, as Emile Durkheim, a principal founder of sociological theory, pointed out more than a century ago.[2] At the Cañon City prisons, these conditions have shifted in more than a century of growth and change. Even though many inmates are in conflict with each other now, as they were in the past, they nonetheless maintain social cohesion because of their shared experiences. Since they experience the same day-to-day routine imposed by the guards, an “us” versus “them” mentality arises. In turn, this opposition to “them” creates strong loyalties among inmates requiring unwavering devotion to the group. To an extent, this prisoner vs. turnkey/corrections officer mentality has been consistent for more than a century. New racial dynamics, however, have transformed the prison social system in recent decades. Trends of mass incarceration have resulted in a different, differently racialized inmate population. Shifts in American history thus underlie and account for shifts in the social organization of Colorado State Penitentiary and other American prisons.

Prison gangs originate outside the walls of a correctional facility. Their backstory lies in racialized street gangs to which many offenders belonged before their incarceration. The ways in which this outside-prison connection has unfolded in the history of the Cañon City requires close attention to social events requiring secrecy and loyalty during their planning and execution— particularly prison riots and escapes or breaks. The Cañon City riot of 1929 and a later riot in 1975, seen in mutual contrast, show that the shifts in solidarity among Cañon City Prison inmates reflected social and ideological changes in wider American society. During the Riot of 1929, participating inmates seem to have valued freedom over imprisonment, so they felt compelled to participate. The Riot of 1975 was different. Unlike the insurrections of the past, it transpired not because of participants’ craving to gain immediate freedom, but because of internal tension produced from prison gangs framed by race. The historical changes from 1929 to 1975 in American society had reconstituted social solidarity and social organization among inmates in Cañon City Prison.

Social solidarity

The division of labor in societies, or organic solidarity, is crucial to understanding solidarity among inmates. This key concept is marked by the transition of traditional to complex societies, as Durkheim noted. Traditional, or mechanical, solidarity is a system that is held together by commonalities due to the formation of close kinships, producing a society that is “more or less organized totality of beliefs and sentiments common to all the members of the group.”[3] Such common beliefs have generally, in traditional human communities, been organized and solidified by religion. The Industrial Revolution, however, created new economic circumstances, driving a corresponding social shift from mechanical to organic solidarity. In industrial Europe and other industrialized regions around the globe, each segment of society is dependent on the others. Therefore, great importance is placed on ensuring that each organ or social group in the larger organism is functioning properly. If one social group stops functioning or begins to function abnormally, the entire organism is thrown off balance.

Durkheim’s theories stress the importance of consensus and cohesion in the functionality of the entire modern socio-economic system. This view can be seen in something as simple as one group’s giving disruptive or contradictory instructions to another. Disorganization causes confusion and chaos. Modern society therefore depends on a collective consciousness constructed within shared moral frameworks. For Durkheim, suicide is a primary demonstration of the failure of social connection and an example clarifying the importance of connections within the collectivity. Suicide severs all social bonds expressing collective consciousness, so demonstrating that the social structure is vulnerable. It also reveals that changes in social structure mirror changes—sometimes devastating changes—in individuals’ behavior. Since prison societies are reflections of American society, social functionalism as described by Durkheim, emphasized in his approach to suicide as the ultimate social breach, usefully suggest how social organization within prisons is shaped.[4]

Criminology, the study of crime and the criminal, is itself a longstanding tradition in European and American thought. Criminals, some have argued, are created by their individual biological or psychological defects. Other participants in a historical discourse on criminality have held that criminals’ social environments are responsible for illegal activities. Gresham Sykes’ path-breaking Society of Captives: Study of a Maximum Security Prison (1958), deploys the theory of social functionalism derived from Durkheim’s foundational sociological theory to unpack the social organization of New Jersey State Prison, a maximum security facility. Sykes suggests in his work still essential to academic study of criminology that subordinate social systems within the larger prison social system determine the workings of the whole.

Although, according to Sykes, individuals enter the incarceration experience with values determined in the outside world, they must in order to survive inside adopt a new belief system allowing them to enter into the prison’s social system. The conditions of prison life, established by the carceral state, determine this alternative social reality. Sykes’ chapter “The Pains of Imprisonment” notes several “deprivations,” including deprivation of liberty and deprivation of heterosexual relationships, to account for the distinctive social system inside prison walls. As he again notes, this system is expressed in, as he terms them, argot roles—linguistic tropes labeling functionality within the social group and affirming a social hierarchy.[5] Sykes organizes the sections of this chapter central to his exposition of prison social arrangements by identifying binaries, opposing but similar roles. He terms these rats and center men, gorillas and merchants, ball busters and real men, toughs and hipsters, and wolves, punks, and fags. Even though the pairings of roles are defined in mutual opposition, inmates as a group (except for rats and center men) maintain the collective consciousness of their shared experience. Attention to the formation of social bonds from a sociological perspective such as Sykes offers shows how vital they are to individuals’ survival behind walls—to the literal prevention of suicide in Durkheim’s terms. Creating, enforcing, and reproducing an “us” versus “them” atmosphere inside prisons was the basic means of the creating of essential social bonds in Trenton in the 1950s, and it remains so in Cañon City today.

Examining prison riots

Analysis of prison riots in relation to social solidarity suggests prisoners’ high levels of secrecy and dedication to not only their common cause in shared confinement, but to the group of other incarcerated persons. Once a sentenced offender becomes an inmate, he exits one social system and enters an alternative system. In doing so, he must form new social relationships. Many of the connections he now establishes are formed through shared experiences. Social bonds nurture him not only mentally but physically. During his incarceration, relationships provide protection and support. Therefore, it is important that a new prisoner form bonds with other inmates that will be useful in his future behind the walls. Examination of the history and motives of the inmates involved in the Riot of 1929 here affirms that the inmates in this early twentieth-century prison event in Colorado were bound by the shared desire of freedom.

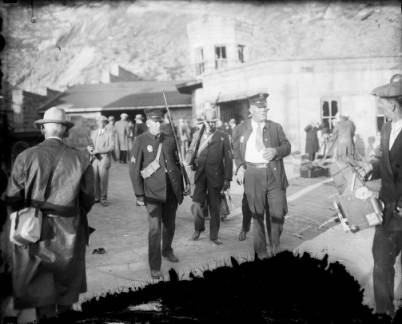

The Riot of 1929 was one of the most gruesome prison riots in United States history. Its brutality can be attributed to the violent backgrounds of the riot’s leaders, James Pardue and Albert A. “Danny” Daniels. Pardue was sentenced to twenty to thirty years for committing armed robberies. Daniels was convicted of two counts of attempted murder and was regarded as “clever and extremely dangerous.”[6] He also was a member of the Oklahoma Terrill gang, notorious for their high-profile robberies and its members’ numerous prison breaks. Indeed, most of the leaders of the 1929 riot had histories of prison escapes. Pardue himself had successfully escaped a Missouri penitentiary and had previously attempted to escape from Cañon City in 1925. His co-conspirator Alfred H. Davis, convicted for conducting a holdup, had escaped a New Mexico penitentiary, then immediately upon his transfer to Cañon City again attempted—this time unsuccessfully—to escape by climbing the prison wall. Davis finally gained freedom briefly on August 28, 1929, but was soon recaptured. Another 1929 co-conspirator, George “Red” Reilley, in CSP for thirty years to life for robbery, had escaped from a California prison. Albert Morgareidge, found guilty of grand larceny, had previously escaped from Cañon City and was recaptured within five days of his break. Leo G. McGenty had committed aggravated robbery and received eighteen to twenty-five years, then attempted to escape on numerous occasions, once by sawing through his prison bars and climbing over the prison wall. Lema “Lemmie” Gross, sentenced to life for murder, was “well versed in escape plots.”[7] He had planned a successful prison break from the Oklahoma State Prison and also attempted an earlier escape from Cañon City, but had been unsuccessful. Only leading 1929 rioter Charles Davis, convicted of assault in the course of a robbery, had no recorded history of escape attempts.

Although the major actors in the 1929 riot had been given sentences of varying severity, they shared the desire for immediate escape from their custodians. Seen from Sykes’ theoretical perspective, unlivable conditions had solidified the connections the men shared. Since inmates such as Charles Davis had been given lengthy sentences, their desire for immediate freedom was still stronger than Morgareidge. They evidently saw it as necessary for their mutual and individual survival to escape the lifelong misery enforced by prison officials. The men involved in the violence that ensued during the Riot of 1929 were therefore socially bonded by their desire for freedom. All but one of the inmates had a history of successful and attempted prison breaks, a powerful shared experience. Their common desire to escape was so strong that each member of the group maintained apparently unbroken secrecy prior to the riot and escape attempt. The shared experience of dismal prison conditions resulted in the inmates’ planning and agreeing to take part in the riot.

By contrast, the inmates involved in the Cañon City riot of 1975 were unified by racialized gang allegiance. Gangs are defined in criminology as “group[s] of two or more individuals who have an ongoing relationship with each other and support one another individually or collectively in the recurring commission of delinquent and/or criminal behavior.”[8] These groups are formed in order to offer social acceptance to society’s rejects, provide a surrogate family to people with disastrous home lives, empower the powerless, support the economically deprived, and protect those who live in fear.[9] Articulation of gangs according to more specific shared experience, such as race, perhaps renders social bonds both outside and inside prison walls more powerful than those seen in the 1929 riot. The creation, enforcement, and perpetuation of “us” versus “them” mentality drives a constant need to prove devotion. Acts of loyalty defining gang membership are usually violent due to these groups’ criminal experiences. Violence in prisons, however, is often directed against rival inmate gangs rather than prison officials because racial divides separate the inmates from other inmates rather than inmates from the guards. Prison riots no longer occur because of the opposition between empowered individuals in blue and the disempowered in orange or green, but instead because of the incarcerated individual’s need to prove his loyalty to his gang and to maintain the integrity and reputation of the gang, his primary social group, among fellow inmates.

Gangs were not defined by race in 1929 as they have increasingly been in the course of the twentieth century. Organized crime gangs, such as mobs, were already in the works by the time of CSP’s 1929 riot. Danny Daniels, one of its principal leaders, had been a member of some of the most notorious crime gangs of the Prohibition era. Unlike later street gangs, however, these earlier gangs were not divided sharply by race. A new typography of gang membership predicated the violence at CSP fifty years later. The Crips street gang led by Black teenagers Raymond Lee Washington and Stanley “Tookie” Williams originated in South Central Los Angeles in 1971.[10] Over the next two decades, smaller street gangs aligned themselves with the Crips, causing membership to increase rapidly. Colorado is still home to twenty-nine known Crip sets. The group is driven by factions but maintains long-term conflict with the rival Bloods gang formed from smaller neighborhood gangs as a method of protection from the Crips in 1972. Fourteen documented Bloods groups now exist in Colorado. One independent group, the 187 Ak Huds, commonly aligns its members with the Bloods when incarcerated. The Latin Kings, a Chicago-based street gang founded in the 1940s, have meanwhile spread throughout the United States, forming chapters in thirteen states, including Colorado. Factions such as the Four Corner Hustlers, Vice Lord Nation, and the Unknown Vice Lords are indigenous to Colorado. California-based Hispanic gangs began forming in 1968. These gangs are divided along members’ allegiance to the Sureños (southerners), and the Norteños (northerners). Historically, the split is a result of cultural differences, and colorism in Mexico that crossed into the United States’ borders.[11] These Hispanic gangs’ influence and chapters have spread to several states in western U.S. including Colorado.[12]

Newly incarcerated members of outside gangs often align themselves with prison gangs in their search for familiarity, protection, and championship. Wider social forces of race, ethnicity, and regional experience shape prison gangs. Although these groups are separate from gangs outside the walls, they have striking commonalities with their outside counterparts. Incarcerated Norteños typically align with the Nuestra Familia, a group originating in the same year apparently by incarcerated Norteños. Sureños are allied with the Mexican Mafia, which was founded in 1957. The Mexican Mafia exerts strong control over Sureños members, even after release from prison, showing how prison and outside social structures influence one another. Bloods and Crips usually join the Black Guerrilla Family or the Moorish Temple gangs inside prison walls.[13]

The Cañon City prison riot of 1975 was a direct result of inside-the-walls gang rivalry between unnamed racialized groups. Even though the gangs were not identified by name, attention to evident alliances and rivalries among involved inmates shows that violence was initially caused by members of the Familia and Mexican Mafia. Disruption began in Cellhouse 1 in the Maximum Security Unit. According to the “Report of the Attorney General on the Events and Causes of the May 18, 1975 Riot at the Colorado State Penitentiary,” an altercation of unknown immediate cause in the cell house bathroom “triggered a simmering feud between two racially identified inmate ‘gangs,’ which was the immediate cause of the violence which followed.”[14] The leaders of the “Chicano” gang, James and Reuben Montoya, along with fellow Chicano inmates, were allegedly intoxicated with inmate-brewed alcohol. In their impaired state, they began insulting other inmates in the mess hall. The Chicano inmates were confronted by a group of Black inmates, four of whom were in possession of inmate-crafted knives. One of the armed inmates, who carried a shank, had been involved in the bathroom incident that happened earlier in the day. Twenty-five inmates participated in the ensuing physical altercation, which was shortly crushed by prison officials. Peace negotiations were begun in an attempt to settle the dispute and the two groups’ respective representatives agreed on a compromise.

Mistakenly, however, the rival groups were both returned to Cellhouse 1 instead of being moved into separate cellblocks. Several hours later, James Montoya was ambushed and stabbed by a Black inmate gang member. While he was being escorted to the hospital, the victim’s brother, Reuben, reportedly said “tell that Nigger that I’m going to get him.”[15] Upon Reuben’s return to Cellhouse 1, the rival gangs began a verbal altercation, then assembled as opposing groups. Glassware thrown and shattered, marking the beginning of a full-blown riot leaving one inmate killed and fifteen wounded. Why did a bathroom insult escalate to a violent riot? Gang mentality, which is influenced by group solidarity, can begin to provide an explanation.[16]

Restoration of equilibrium and social order was beyond the reach of words alone. In the eyes of other inmates and rival gangs, such a resolution would have meant the loss of respectability and tarnishing of reputation. Given the prison’s lack of precursory safety measures, physical violence was almost inevitable. The original bathroom incident only involved four people, but the next stage of the conflict, the quarrel in the mess hall, involved about twenty-five. Group allegiance was so strong among these individuals that twenty-one people injected themselves into a situation that they were not originally involved. They risked their lives because of their loyalty to their respective groups, the social bond along which they aligned their survival and dignity as prisoners.

Prisons as communities

Prison social structure, according to functionalist theory such as Sykes’ interpretation of relations in the Trenton facility in the 1950s, is fragile despite its potential for violence, hence susceptible to change. Cañon City prisons have accordingly changed over time to reflect the social system of greater American society. Social solidarity is vital to the healthy functionality of any human community lest, in the absence of a moral framework, complete chaos ensue. When conflict does arise, society’s members attempt to return opponents to harmonious equilibrium. Analysis of prison social events with their compelling secrecy, trust, and cohesion among groups—here most importantly prison riots and prison breaks—shows how these groups’ organization has evolved over time. In the Cañon City Riot of 1929, social bonding came from a desire for freedom, but forty-six years later, the Riot of 1975 revealed a shift to racially grounded social cohesion. In the 1970s as now, members of street gangs incarcerated for illegal activity on the outside bring gang allegiances with them into prison. The similarity of street and prison gangs mirrors the interaction of outside and inside societies more generally. The evolution of social solidarity as seen through the Cañon City Prison Riots of 1929 and 1975 reveals how wider historical trends play out behind prison walls.

The age of mass incarceration began several years after the 1975 riot. Michelle Alexander’s New Jim Crow (2010), a hugely influential essay on the racialization of American justice, may itself have assumed agency in the future construction of societies of captives. Alexander unveils the invisible operation of systematic oppression that targets people of color by incarcerating them at higher rates than their Caucasian counterparts.[17] This powerful and influential work has already transformed an American consciousness of the nexus of race and criminalization, and it may as well come to shape the consciousness of those in prison as a new unifying ideology. If the more than two million Americans in correctional facilities are able to settle their differences in the community of oppression Alexander attributes to them, prisoners’ solidarity may eventually resume some of its character in the first Cañon City riot examined here, the violence of 1929, in which freedom from prison—not alliance in prison—was the participants’ primary goal.

[1] Originally researched and drafted by Kyana Bell.

[2] Emile Durkheim, On Mechanical and Organic Solidarity, ed. Peter Kivisto (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 41.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Gresham Sykes, The Society of Captives: Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), 63-65.

[6] Wayne Patterson, Slaughter in Cell House 3: The Anatomy of a Riot (Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing), 8.

[7] Ibid., 9.

[8] Michael Carile, “A Personal Journey into the World of Street Gangs: Why Gangs Form,” Missouri State University, 2002, http://people.missouristate.edu/michaelcarlie/what_i_learned_about/gangs/whyform/conclusion_why_gangs_form.htm.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Celeste Fremon, “Behind the Crips Mythos,” Los Angeles Times, November 20, 2007.

[11] Norma Mendoza-Denton, Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice Among Latina Youth Gangs (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell), passim.

[12] Robert P. Turtle, “21st Century Outlaws: An Information Manual on Gangs and Security Threat Groups,” 2001, Museum of Colorado Prisons, “Gangs” exhibit.

[13] Ibid.

[14] State of Colorado, Department of Law, “Report of the Attorney General on the Events and Causes of the May 18, 1975 Riot at the Colorado State Penitentiary,” June 18, 1975, 5.

[15] Ibid., 12.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010), 20.