The focus of my research is on the early decades of the last century, but I am very curious how much has changed in Martinique on the racial front since then, and what insights a comparison between the evolution of racial relations in the United States and the French Antilles might yield.

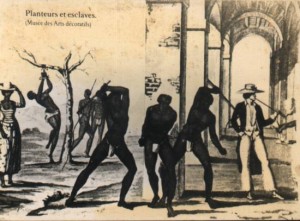

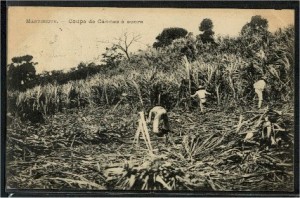

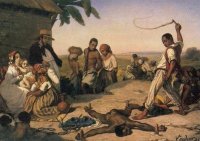

According to the Caribbean historian Christian Filostrat, French Antillean colonial society was divided into several levels, according to caste and class. At the top were the grands blancs, or békés, the white Créoles who had made their fortunes as planters, with their wealth from sugar cane and slavery continuing through generations. Next were the metropolitans, colonial administrators and their families who circulated between the hexagon (mainland France) and its periphery. At the bottom of the scale in white society were the petits blancs, the mostly uneducated descendants of indentured servants who worked first as overseers and other functionaries of the great plantation owners; they later became small farmers and artisans as well. Lacking capital and status, their only asset lay in the color of their skin. (Left, a French West Indian Sugar Plantation, 1762)

According to the Caribbean historian Christian Filostrat, French Antillean colonial society was divided into several levels, according to caste and class. At the top were the grands blancs, or békés, the white Créoles who had made their fortunes as planters, with their wealth from sugar cane and slavery continuing through generations. Next were the metropolitans, colonial administrators and their families who circulated between the hexagon (mainland France) and its periphery. At the bottom of the scale in white society were the petits blancs, the mostly uneducated descendants of indentured servants who worked first as overseers and other functionaries of the great plantation owners; they later became small farmers and artisans as well. Lacking capital and status, their only asset lay in the color of their skin. (Left, a French West Indian Sugar Plantation, 1762)

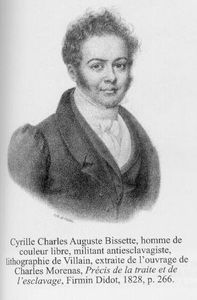

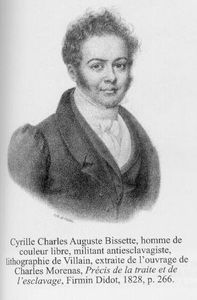

Martinique imported more slaves in total than the United States did, if we don’t count slaves imported to Louisiana before the purchase. Nearly all non-white Martinicans are descended from slaves. However, as early as the 16th century, a class emerged of mixed-race gens de couleur. It was comprised of slaves and a small number of free people who had either bought or been granted their freedom. Artisans, entrepreneurs, small landholders, or low-level bureaucrats, families in this class, after abolition, became the bedrock of the black bourgeoisie. At different points in France’s history, the gens de couleur, with their education and aspirations, either served as a useful buffer to the white French colonialists, or posed the most potent threat to the social order. Left is a picture of Cyrille Charles Auguste Bissette, a free man of color who was elected to represent Martinique in the National Assembly, but was charged with sedition for his support of emancipation and civil rights for African-descended people, convicted, and sentenced to banishment. Other gens de couleur were eager to keep their distance from “les noirs,” whom they considered inferior. The largest and most powerless color/caste group on the island has always been the noirs, the black people who performed unskilled or low-skilled labor. After the abolition of slavery, the békés enticed over 25,000 Asians~ mostly from China and India ~ to work as “coolies” on the plantations alongside the “noirs.”

Martinique imported more slaves in total than the United States did, if we don’t count slaves imported to Louisiana before the purchase. Nearly all non-white Martinicans are descended from slaves. However, as early as the 16th century, a class emerged of mixed-race gens de couleur. It was comprised of slaves and a small number of free people who had either bought or been granted their freedom. Artisans, entrepreneurs, small landholders, or low-level bureaucrats, families in this class, after abolition, became the bedrock of the black bourgeoisie. At different points in France’s history, the gens de couleur, with their education and aspirations, either served as a useful buffer to the white French colonialists, or posed the most potent threat to the social order. Left is a picture of Cyrille Charles Auguste Bissette, a free man of color who was elected to represent Martinique in the National Assembly, but was charged with sedition for his support of emancipation and civil rights for African-descended people, convicted, and sentenced to banishment. Other gens de couleur were eager to keep their distance from “les noirs,” whom they considered inferior. The largest and most powerless color/caste group on the island has always been the noirs, the black people who performed unskilled or low-skilled labor. After the abolition of slavery, the békés enticed over 25,000 Asians~ mostly from China and India ~ to work as “coolies” on the plantations alongside the “noirs.”

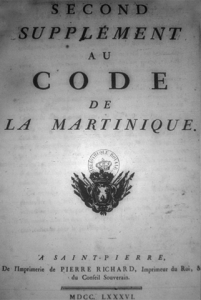

Keeping all this straight was a challenge, especially since whiteness had so many privileges that must be preserved for the economic and social system of the island to function. The purity of white “blood” was an obsession with the minority white population (in 1741, over 80% of the island population was enslaved) as well as mainland France. Things were complicated even further when after the French Revolutionaries, declaring “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité”, abolished slavery in 1794, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802 (with the full approval of his wife Josephine, who was born in the town I’m staying in now). The French economy depended on the vast pool of unpaid labor in its Antillean colonies.  So starting in 1685 and continuing through several revisions until 1848, when slavery was abolished for the second and final time, French relations with African-descended people in its colonies and territories was legally structured by the Code Noir. Covering every aspect of every possible contact between whites and blacks (both slave and free)~ from religious instruction to commercial and sexual relations~ it outlined with French attention to detail that makes American Jim Crow laws look like student council rules, all black-white interracial responsibilities, duties, constraints and privileges.

So starting in 1685 and continuing through several revisions until 1848, when slavery was abolished for the second and final time, French relations with African-descended people in its colonies and territories was legally structured by the Code Noir. Covering every aspect of every possible contact between whites and blacks (both slave and free)~ from religious instruction to commercial and sexual relations~ it outlined with French attention to detail that makes American Jim Crow laws look like student council rules, all black-white interracial responsibilities, duties, constraints and privileges.

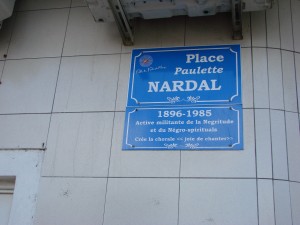

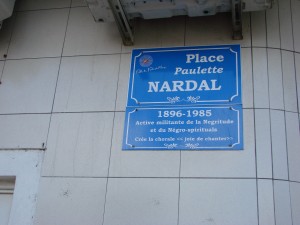

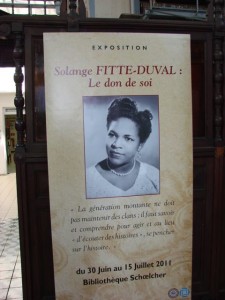

The Martinican gens de couleur produced most of the Négritude writers, the surrealists, the first black writer to win the Prix Goncourt (like the Mann-Booker or Pulitzer for fiction), and the psychiatrist, philosopher and revolutionary, Frantz Fanon. Though historically the gens de couleur were anxious, especially through times of French social upheaval, about being thrown back into the pit of slavery or losing their few privileges and status to be lumped in with the “blacks,” the interwar generation was the first to both interrogate and affirm their connections to Africa and combat colonialism on a global scale.

I started my day at the small but richly curated Musée Régionale de l’Histoire et l’Ethnographie. Situated in a charming and well-preserved Créole mansion set back from the Boulevard Charles de Gaulle, the permanent exhibit is centered on a recreation of daily life in the household of a Créole de couleur family at the end of the 19th century.

As I emerged from the stairwell I was confronted by the meticulous recreation of a family in a drawing room. It’s almost embarrassing to admit, but I had that bougie moment of satisfaction that seeing a historical representation of black people tastefully dressed in a well-appointed environment inspires. Good quality furniture, a few pieces of modest but original art, open books lying about; the mother reclining gracefully in her chair, the father comfortably paternal in his three-piece suit and mustache. For another moment, I tried to imagine what it would have been like to live in that house and its illusions of security. But the next minute I was thinking, they are barely two generations from slavery, and the békés and metropolitans still run everything as if slavery still existed for the majority of African-descended people on the island. You could not possibly be as comfortable as you look.

As I emerged from the stairwell I was confronted by the meticulous recreation of a family in a drawing room. It’s almost embarrassing to admit, but I had that bougie moment of satisfaction that seeing a historical representation of black people tastefully dressed in a well-appointed environment inspires. Good quality furniture, a few pieces of modest but original art, open books lying about; the mother reclining gracefully in her chair, the father comfortably paternal in his three-piece suit and mustache. For another moment, I tried to imagine what it would have been like to live in that house and its illusions of security. But the next minute I was thinking, they are barely two generations from slavery, and the békés and metropolitans still run everything as if slavery still existed for the majority of African-descended people on the island. You could not possibly be as comfortable as you look.

The museum curators presented that tension in a wonderful way, I discovered, as I turned around to examine the opposite wall. There was a small but resonant collection of artifacts from slavery: an oil-on-wood portrait of a prosperous and bright-looking Age of Enlightenment white man~ a ship’s captain who had made his fortune sailing the Atlantic triangle. I examined pages from packing diagrams from his ships: Africans, sugar, rum. Pages from the Code Noir.

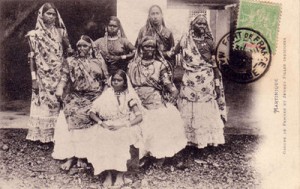

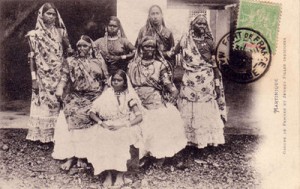

One hallway was devoted to the traditional dress of “mûlatresses” and black women. Several cabinets of dolls in regional and occupational varieties of dress illustrated the various codes and symbols the women employed. The voluminous dresses, which often mix a cacophonous palate of patterns that somehow look just right together, evoke the skirts and blouses seen in many West African cultures.

One hallway was devoted to the traditional dress of “mûlatresses” and black women. Several cabinets of dolls in regional and occupational varieties of dress illustrated the various codes and symbols the women employed. The voluminous dresses, which often mix a cacophonous palate of patterns that somehow look just right together, evoke the skirts and blouses seen in many West African cultures.

One of the methods of keeping the races distinct, even after the abolition of slavery, was to require that African-descended women cover their hair in public. Leave it to black women to take a sign of legal and social subjugation and turn it into art. The turbans are still an expressive and vital part of Martinican women’s dress, especially for special occasions, as several websites attest. Bright materials are intricately woven around the head, employing an entire vocabulary of meanings that convey not only status and occupation, but also romantic availability. For example:

La façon dont était noué le foulard, le nombre de pointes qui dépassait donnait des indications sur l’état du coeur de la belle. Par exemple : une pointe qui dépassait signifiait : “coeur à prendre”; deux pointes : “déjà pris” ; trois pointes : “femme mariée”.”

La façon dont était noué le foulard, le nombre de pointes qui dépassait donnait des indications sur l’état du coeur de la belle. Par exemple : une pointe qui dépassait signifiait : “coeur à prendre”; deux pointes : “déjà pris” ; trois pointes : “femme mariée”.”

(The way in which the headscarves were knotted, the number of points which jutted out, gave indications of the state of heart of the beauty. For example: one point jutting out signifies: “heart for the taking” two points: “already taken” three points: “married woman”)

Unfortunately, photography is forbidden in the museum, but I have tried to find some on-line pictures that convey the sort of thing I saw. The photos here, titled “Type Créole” and “Type Créole (femme de peuple)” are from the collection of the Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, in Aix-en-Provence, where I did research during the summer of 2009.

I was intrigued by a portrait of Jenny Alpha, the Martinican singer and actress who floats in and out of the circles I’m studying,  by the French surrealist Francis Picabia (I use a reproduction of his stationery to write put notes under my students’ doors in Paris.) titled “La mûlatresse.” I later found her just-published autobiography (she passed away just last year at the age of 100) in a bookstore down the street. She was sent to Paris by her bourgeois parents to get a teaching certificate and find a husband among the Martinican young men studying in the professional schools at the universities there, but she decided that she wanted to be a comedienne. A Martiniquaise developing a career as a comedienne in interwar France was impossible, though. I just started reading her book while refreshing myself with a citronnade at an outdoor café, and only reluctantly put it down when my lunch companion arrived.

by the French surrealist Francis Picabia (I use a reproduction of his stationery to write put notes under my students’ doors in Paris.) titled “La mûlatresse.” I later found her just-published autobiography (she passed away just last year at the age of 100) in a bookstore down the street. She was sent to Paris by her bourgeois parents to get a teaching certificate and find a husband among the Martinican young men studying in the professional schools at the universities there, but she decided that she wanted to be a comedienne. A Martiniquaise developing a career as a comedienne in interwar France was impossible, though. I just started reading her book while refreshing myself with a citronnade at an outdoor café, and only reluctantly put it down when my lunch companion arrived.

After 90 minutes examining the historical treasures on the first floor, I went downstairs to the temporary exhibit, an amazing history of the forests and plant-life of the island and their economic and cultural impact. I wish that an exhibition folio had been on offer, but the little museum doesn’t even have a gift shop. It took me almost three hours to go through the museum; I was the only visitor there during the whole time.

I emerged into the brilliant, humid air churning with questions: do the békés still exist? What was it like for them to live, wealthy and powerful, but with the penumbra of the black and deprived presence all around them, and essential to their continued success? What are the current distinctions of color and caste within Martinican society? Is there an independence movement in Martinique? I had just enough time to dip into a bookstore to look for some answers to these questions before the next item on my day’s agenda: lunch with a young woman who was raised in Martinique and is attending graduate school in the United States. I was hoping that she would be able to give me insight into the island’s racial dynamics from the perspective of the next generation of adults. Tomorrow~ my very thought-provoking conversation with a student I will call “Lucie, ” who is uniquely posed to view both the black and white worlds of Martinique.

One of the first questions I had for Lucie was whether “békés” still exist, and if “béké” ~ a word I have usually heard spoken with contempt~ is a word still used to describe the descendents of planters who established their multi-generational wealth through the slave trade, sugar cane, and rum. Oh, yes, she told me. They still exist, are still called “békés,” and still control all of the wealth on the island. There are around 5000 of these families, but they are very insular. They own all of the grocery store chains, car dealerships, rum distilleries (all of them family businesses several hundreds of years old), and major real estate. They all go to Lucie’s school, even if it involves a 4-hour round-trip daily commute. They go to France or Miami for their university degrees, and return to run the family businesses. They only marry each other~ even to marry a French white person would be unthinkable. According to Lucie, they are deeply racist.

One of the first questions I had for Lucie was whether “békés” still exist, and if “béké” ~ a word I have usually heard spoken with contempt~ is a word still used to describe the descendents of planters who established their multi-generational wealth through the slave trade, sugar cane, and rum. Oh, yes, she told me. They still exist, are still called “békés,” and still control all of the wealth on the island. There are around 5000 of these families, but they are very insular. They own all of the grocery store chains, car dealerships, rum distilleries (all of them family businesses several hundreds of years old), and major real estate. They all go to Lucie’s school, even if it involves a 4-hour round-trip daily commute. They go to France or Miami for their university degrees, and return to run the family businesses. They only marry each other~ even to marry a French white person would be unthinkable. According to Lucie, they are deeply racist. I have an unhealthy curiosity about the békés. What would it be like to know that your fortune and status, preserved throughout centuries, was built on the exploitation of suffering of enslaved human beings~ and not to care? To still have contempt for the descendants of those who made your fortune? To depend upon people for whom you have no respect to continue to build your wealth?

I have an unhealthy curiosity about the békés. What would it be like to know that your fortune and status, preserved throughout centuries, was built on the exploitation of suffering of enslaved human beings~ and not to care? To still have contempt for the descendants of those who made your fortune? To depend upon people for whom you have no respect to continue to build your wealth?