Paulette Nardal was born in Martinique in 1896, the eldest of 7 sisters. Her father was the first black engineer in Martinique, but the racism of colonial society prevented him from having a job title that reflected the work he actually did for the island and the French government. Paulette and her sister Jane were among the first of a small group of Martiniquaises who went to Paris to earn university degrees between the wars. Nardal earned a degree in English, and although her dissertation was on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Nardal was among the first to call for scholarly studies of African American and other black literatures. She wrote for Aimé Césaire’s paper, L’Etudiant Noir, and later co-founded a newspaper~ La Dépêche Africaine and La Revue du Monde Noir. Her work in all of these publications reflected her interest in exploring black culture in a global context. The Dépêche had a page devoted to events in North and Latin America, while the Revue was bilingual (French and English) and played a major role in introducing francophone writers to the work of American writers such as Langston Hughes and Claude McKay. In the first issue of La Revue du Monde Noir, Nardal expressed the goals of the publication:

Paulette Nardal was born in Martinique in 1896, the eldest of 7 sisters. Her father was the first black engineer in Martinique, but the racism of colonial society prevented him from having a job title that reflected the work he actually did for the island and the French government. Paulette and her sister Jane were among the first of a small group of Martiniquaises who went to Paris to earn university degrees between the wars. Nardal earned a degree in English, and although her dissertation was on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Nardal was among the first to call for scholarly studies of African American and other black literatures. She wrote for Aimé Césaire’s paper, L’Etudiant Noir, and later co-founded a newspaper~ La Dépêche Africaine and La Revue du Monde Noir. Her work in all of these publications reflected her interest in exploring black culture in a global context. The Dépêche had a page devoted to events in North and Latin America, while the Revue was bilingual (French and English) and played a major role in introducing francophone writers to the work of American writers such as Langston Hughes and Claude McKay. In the first issue of La Revue du Monde Noir, Nardal expressed the goals of the publication:

“To study and make known by the voice of the press, books, conferences and courses of study, everything that concerns the BLACK CIVILIZATION and the natural riches of Africa, the homeland thrice sacred to the black race.

To create between Blacks the world over, without distinction of nationality, a intellectual and moral bond which permits them to know each other better, to love each other fraternally, to defend more effectively their collective interests and to represent their Race…

We stand and will always stand for PEACE, WORK, AND JUSTICE through LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY.”

La Dépêche was closed down by the French government (which had originally given it some funding) over concerns that it was becoming too radical, especially after Marcus Garvey’s organization shared office space with their editors. The Revue, which was independent of external funding, lasted only a year, finally closing down due to financial pressures.

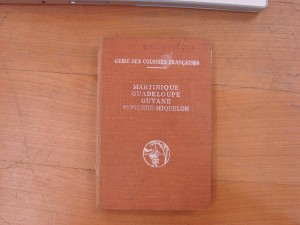

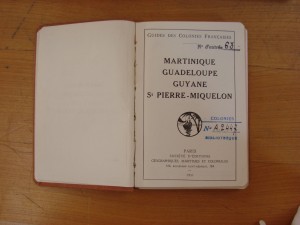

In 1931, the French government commissioned Nardal to write a guide to Martinique. The Guide is in the rare books collection of the Bibliothèque Schoelcher.  I asked permission to photograph each page, and it was granted immediately. The librarian even asked if I had my own camera, as if he were ready to lend me one if I did not. The library closed at one on Wednesday (I had thought the fermature was at 1:30), and I of course worked up to the last minute~ when I looked up, the librarian was gone and the office lights were out, and I had a rare book in my hands. I waited for someone to return, but the staff was eager to begin their celebrations of Bastille Day, so I hid the book far back on the librarians’ computer keyboard, rolling it carefully under the desk. When I saw the librarian downstairs making for the door I , told him, “J’ai caché le trésor Nardal” and made him come back upstairs with me. He took the little book out of my hiding place, and tossed it on the top of a hodgepodge of books stacked on a bookshelf.

I asked permission to photograph each page, and it was granted immediately. The librarian even asked if I had my own camera, as if he were ready to lend me one if I did not. The library closed at one on Wednesday (I had thought the fermature was at 1:30), and I of course worked up to the last minute~ when I looked up, the librarian was gone and the office lights were out, and I had a rare book in my hands. I waited for someone to return, but the staff was eager to begin their celebrations of Bastille Day, so I hid the book far back on the librarians’ computer keyboard, rolling it carefully under the desk. When I saw the librarian downstairs making for the door I , told him, “J’ai caché le trésor Nardal” and made him come back upstairs with me. He took the little book out of my hiding place, and tossed it on the top of a hodgepodge of books stacked on a bookshelf.

Scholars have speculated why Nardal took this assignment from the French government, especially after the tensions associated with La Dépêche Africaine. My guess is that they paid her well, and that it enabled her to do something positive for the island~ her book details not only its sights, but its history, economy, culture, and peoples~ while promoting what was at the time a potential new source of revenue for the island: tourism. Other authors wrote the entries for Guadeloupe, Guyane, and St. Pierre-Miquelon.

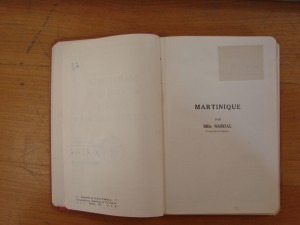

Here’s a sample from the opening page of the guidebook. I have provided the original, for you francophiles, and my own off-the-top-of-my-head literal translation.

Here’s a sample from the opening page of the guidebook. I have provided the original, for you francophiles, and my own off-the-top-of-my-head literal translation.

1. Avant-propos

Le Martinique ! Ce nom aux claires syllables, évoque tout un passé brillant : suprématie de la petite île qui, au XVIII s., devint le ch.-1 des Antilles. On disait alors : les seigneurs d’Haiti, les messieurs de la Martinique et les bonnes gens de la Guadeloupe. A cette époque fleurient dans l’Ile aux Fleurs les grâces d’un siècle brillant et policé dont on peut retrouver un écho affaibli chez les actuels habitants de l’Ile aux Fleurs. Manieres un peu désuètes. Vieille politesse française. Légére précosité de  la musique et de la danse. Recherche du costume. Expressions vieillies. Souvenirs galants ou aimables. Lent et doux parler.(Martinique! This name of clear syllables evokes a brillant past: the preeminence of the little island which, in the XVIII century, became the first chapter of the Antilles. One used to say: the lords of Haiti, the misters of Martinique and the good people of Guadeloupe. In this epoch the graces of a brilliant and orderly century flourished on the Isle of Flowers in which one can recognize a weak echo in the present inhabitants of the isle. Manners a little old-fashioned. Old-style French politeness. A light precocity in music and dance. A sense of style. Old-people expressions. Relics of gallantry or considerateness. A slow and sweet way of speaking.) (Note to my colleagues in the field: These photos are from the copy of the Guide held by the Archives d’Outre-Mers in Aix-en-Provence~ I photographed only the cover and title pages, and due to lack of time, transcribed the passages I thought most significant at the time. Of course, since my visit to Aix, I’ve discovered that the whole book is important to my project, so photographed every page of the volume here in Fort-de-France.)

la musique et de la danse. Recherche du costume. Expressions vieillies. Souvenirs galants ou aimables. Lent et doux parler.(Martinique! This name of clear syllables evokes a brillant past: the preeminence of the little island which, in the XVIII century, became the first chapter of the Antilles. One used to say: the lords of Haiti, the misters of Martinique and the good people of Guadeloupe. In this epoch the graces of a brilliant and orderly century flourished on the Isle of Flowers in which one can recognize a weak echo in the present inhabitants of the isle. Manners a little old-fashioned. Old-style French politeness. A light precocity in music and dance. A sense of style. Old-people expressions. Relics of gallantry or considerateness. A slow and sweet way of speaking.) (Note to my colleagues in the field: These photos are from the copy of the Guide held by the Archives d’Outre-Mers in Aix-en-Provence~ I photographed only the cover and title pages, and due to lack of time, transcribed the passages I thought most significant at the time. Of course, since my visit to Aix, I’ve discovered that the whole book is important to my project, so photographed every page of the volume here in Fort-de-France.)

After the second World War, when Martinique became a “département” (state) of France and French women (including those in Martinique and other “outre-mers” (overseas) départements) got the right to vote, Nardal founded a Catholic women’s group~ Rassemblement Féminin~ and was both the director and editor of its newletter, La femme dans la cité. The group focused on encouraging women to vote and be civically engaged while addressing the dire problems facing Martinican families at the time: high infant mortality rates, rampant illness due to unsanitary conditions within and outside of the home, and work conditions not terribly different from those of slavery. The Rassemblement Féminin focused its efforts on persuading women of the importance of getting to the ballot box (exasperated by Martinican women’s political apathy, Nardal wrote several jermiads in her newsletter about voting, including “De la paresse intellectuelle”/”Intellectual laziness”) and what we would now call “domestic science”~ running workshops on infant nutrition, hygeine, and other domestic knowledge.

When in France, Nardal and her sisters held salons in their apartment in the Parisian suburb of Clamart, where artists, students, writers, musicians and other intellectuals from throughout the black diaspora met to discuss the future of “La Race,” sing (all of the Nardal sisters were talented musicians), and drink tea (there are reports that no alcohol was served chez Nardal, so the men often went out to a bar together afterwards). In 1937, Nardal worked for a time in Senegal with her friend the Négritude poet and later first president of a free Senegal, Léopold Sedaar Senghor, rallying resistance to the invasion of Ethiopia.

A fierce and untiring feminist, a devout Catholic, an energetic writer, editor, and translator, Nardal never married. From her compassionate portrait of a Martinican domestic worker living unhappily in Paris (“En Exile”) to her efforts to promote knowledge and appreciation of Antillean culture to her multi-faceted efforts to facilitate conversations about race across cultural, national, and linguistic borders, Nardal’s work still resonates today.

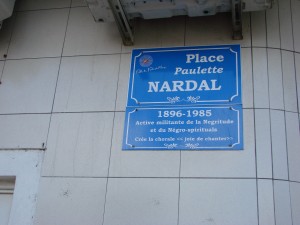

There is a Place named after her in central Fort -de- France. The street sign reads: “Paulette Nardal 1896-1985. Active militante de la Negritude et du Negro-spirituals. Crée de chorale “joie de chanter.”

2 Responses to Paulette Nardal, une femme “evoluée”