Palatine and Capitoline Hills, and the Forum

Overview by S. Thakur, S. Ashley, and C. Siddoway, Colorado College.

List of readings appears at bottom of page.

Aspects of the regional geology — in particular the fluctuations in sea level, volcanism, and hydrography — supported society and encouraged optimum use of earth resources. In turn, the topography of the sites affected their social function and the development of the societies themselves. This intersection of topography and history (mythological and “real”) is seen in literature and the archaeological record. Classical literature and archeological records reveal how events and places are perceived and imagined, and how topography and the natural environment influences cultural productions, and vice-versa. Rome’s ancient city center is the ideal space to study these interactions, and to discover how societal beliefs can affect change on the local environment.

Rome offers glimpses of past human constructions through such features as the campus Martius, or field of Mars as it was known in antiquity, an area located outside of the limits of the ancient city, temples dating from the Republican period of ancient Rome (3rd century-early 1st BC). The temples would have marked the ancient entrance to the city , along which triumphal armies and their generals advanced, in a parade which would have culminated atop the Capitoline hill. These temples were bestowed with booty and trophies from battles, dedicated by the commanding general to a deity he identified as responsible for the victory. The temples were also the site of innovation, with architectural style and materials influenced, on occasion, by the location of the Roman victory. Of note was the dramatic increase (over 12 feet) in ground level from antiquity.

The Palatine, Forum and Capitoline are all difficult sites to study because of their long histories and the varied states of preservation, yet they are wonderfully illustrative of the multi-disciplinary approach needed to understand them today.

A passage attributed to the Roman leader Camillus, from Livy’s History of Rome book 5 (sections 51-54), encourages the Romans not to abandon their homeland for the nearby city of Veii, recently taken by the Romans and unspoiled by Gallic attack. The quotation illustrates the Romans’ knowledge and understanding of the importance of their local topography:

“Not without good reason did gods and men choose this spot as the site of a city, with its bracing hills, its commodious river, by means of which the produce of inland places can be brought and over-seas supplies obtained, a sea near enough for all useful purposes, but not so near as to be exposed to the danger from foreign fleets, a district in the very center of Italy- in a word a position singularly adapted by nature for the expansion of a city… Our ancients left us certain rites and ceremonies which we can only duly perform in Rome. For the Vestals surely there is only that one abode…” etc.

The exhortation was offered after Brennus, leader of the Gauls, had sacked Rome,, circa 396 BC, and uttered the famous retort vae victis. Needless to say, the Romans followed Camillus’ urging and stayed in Rome.

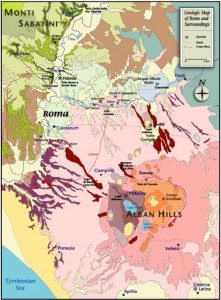

The geological history involving sea level fluctuations, volcanism, and ground water is responsible for the suitability of the “Seven Hills of Rome” for human civilization. Inundated by ocean water in the ‘geologically recent’ past, from 3.5 million to 880,000 years ago, the area surrounding Rome accumulated deposits of marine claystones that now form a stable ‘bedrock’ beneath the highest parts of the city, including the Vatican, Janiculum, and Monte Maria Hills. Regression of the sea and re-establishment of the Tiber River introduced permeable sand and conglomerate in to the environment– materials that contribute to rich groundwater resources to support agriculture and migratory birds. Products of pyroclastic eruptions — the ‘tufos’ that provide remarkable building stone and materials for the famed pozzolana concrete– are the third element within the fundamental geological context. The pyroclastic sheets formed a low gradient surface for transportation of water from the Alban and Sabatini Hills to the nascent city of Rome, later to provide a template for the hydrological engineers who constructed aquaducts and roads for the Empire. With geological faults to influence the locations of springs and deposits of travertine, the optimal combination of geological resources to support human civilization were in place.

Within this paleoenvironmental context, the vestiges of the residences of the founders of Rome are best understood. The Palantine Hill is the site of the archaic houses that date to the 9th/8th c. BC, proximate to the date given in Livy’s account of the founding of Rome. The structures are emblemmatic of an intersection between history and myth, vis a vis the story of Rome’s foundation and the characters Romulus, Remus and Hercules, whose myths tie to the natural topography and environment of the ancient city. In particular, the Tiber River and wetlands, below the Palatine Hill, feature in the Romulus story in Livy.

The question of “why here?” for this location for the city of Rome and center of the Roman empire can only be addressed from diverse disciplinary standpoints that transcend the span of time: the Palatine (from which we get the word ‘palace’) has been in a state of almost constant occupation and renovation from the 9th c BC until the Middle Ages. The intersection of time, perception, priority and disciplines could in a sense be embodied by the collections of the archaeological museum. Among the imported stone artworks are basalt sculptures which adorned the library built by the emperor Augustus (end of 1st c. BC/beginning of 1st AD) adjacent to his house and the Temple of Apollo; these mark the Roman conquest of Egypt during his reign. A second example is the opus sectile floor section from the emperor Tiberius’ (early 1st c AD) palace. Like the Augustan statuary, the floor itself was a statement of Roman imperial power and sway, with marbles coming from no less than 4 distinct regions of the empire. The importation of natural materials became a distinctive hallmark of Roman architecture and power, recorded by something as “functional” as a floor.

Forum

The descent from the Palantine Hill to the Forum is achieved upon a pavement of volcanic stone (and still used to this day). The location of the Forum in the cityscape/landscape corresponds to a valley between the Capitoline and Palatine Hills, one that was susceptible to flooding in antiquity. Feats of Roman engineering ensure that it did and does drain properly. The orientation of the forum was altered as the political landscape changed, becoming a closed focused space and one upon which ideals of appearance and form were imposed. The structures looked uniformly “white”, thanks to the import of marbles of varied origins. The Arch of Titus is built of marble from mount Pentelicon in Athens, the Greek island of Paros supplied the marble for the Temple of Castor and Pollux, the Temple of Mars the Avenger from Luna/Cararra, the Arch of Constantine from Numidian (N. African), the yellow in the Pantheon from Tunisia. Local volcanic tuff and travertine allowed for engineering advances, the fertility and productivity of the realm allowed for discretionary functions an development of monumental art; the examples from Rome have influenced every city that has followed, not least during the urban planning of the modern age.

Capitoline

The Capitoline Hill is a juncture of three critical worlds upon landscape and culture. The three are: the classical world of antiquity, carrying the imprint of the emperors of Rome; the world of the Renaissance, shaped by the princes of the Church; and the modern–defined by Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel, by Mussolini, and by the more anonymous leaders of the almost fifty governments since the last war.

The Capitoline Hill_SusanAshley

Ancient sites were razed (and used for fill) for the construction of the Vittorio Emmanuele monument. The hill was the site of various temples in antiquity, on the upper hill (where the church now stands) the citadel proper and Temple of Juno. Underneath the Capitoline museum lie the foundations of a massive temple. The large ashlar blocks extend to 40’ in depth and could have supported the largest temple in the ancient world (60 meters square), yet the temple the platform did support was much smaller than its footprint. The temple was tripartite and dedicated to Juno, Minerva and Jupiter. Known as the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, it was the end-spot of imperial triumphs and its walls held copies of treaties Rome signed with other nations. Even as Rome’s power grew its original cult statues remained, made in terracotta, as a reminder of Rome’s humble origins.

The preceding topics were introduced on the first day of the SAIL (6/25/13).

The day concluded on a festive note: Pizze i vine in piazza!

An interdisciplinary exploration of Rome could not be achieved without a visit to the most celebrated edifice in the world: The Pantheon. Geometrical design elements achieve the union of concept, design, and site that is the Pantheon. The sphere, triangle, and rectangle combine to create sacred geometry.

(Remarkably, accommodation at the Hotel Navona was situated just one block from the remarkable structure, passing through piazza Sant‘Eustachio , the site of one of the most historic espresso cafes in Rome! Il Caffè è un’antica caffeteria e torrefazione a legna nata nel 1938: .)

Readings:

- Livy History of Rome Book I: 1.1-1.17 (selections on the founding of Rome: Romulus and Remus and the hills) [eText: University of Virginia]

- Ovid, Fasti entries for Jan 11, Feb 15, Feb 17, Feb 21, Feb 23, Mar intro, Mar 15, Apr 21, May 9, May 14, June 9 [Poetry In Translation] [Ovid’s poetic calendar ties myth to specific locales in Rome we will be visiting; of interest are how topography and history influence cultural production(s)]

- Juvenal, Satire 3 [Poetry in Translation] [Juvenal’s short poetic satire on life in Rome is, like Ovid’s, also a commentary on Rome’s topography and monuments]

- Vitruvius, de architectura Book 2 Chap.3-7 (inclusive), Book 3 Chap. 2-4 (inclusive), Book 4 Chap. 4-6 (inclusive), Book 5 (all) [University of Chicago][Vitruvius’ work, still influential amongst architects today, describes various building materials and practices, and illustrates how ancient Romans were well aware of the natural world. The Vitruvius can be read rather cursorily, depending upon a participant’s level of interest]

- DiRita, D. & Giampaolo C., “Ancient Rome was Built with Volcanic Stone from the Roman Land,” 2006, in GSA Special Paper 408, p. 127-131, 10.1130/2006.2408(06).

- Jackson, Marie D. “Vulcan’s Masonry,” Natural History, 116 (2007): 40-45.

- Alvarez W., The Mountains of Saint Francis (Part II), W.W. Norton, 2009, 288 pp. [Books: Amazon]

- Heiken G. et al, Seven Hills of Rome (Chapters 1-2), Princeton University Press, 2005, 245 pp. [Available on Amazon]

- Wayman, Erin, “The Secrets of Ancient Rome’s Buildings,” Smithsonian Magazine, 2007.

Notes provided by S. Ashley, S. Thakur, and C. Siddoway of Colorado College.