It’s 8:44 PM on a Sunday. The night has shaped up like most other Sundays past; I’m tackling a weekend’s load of homework while flipping through my liked songs on shuffle. My usual rotation of Action Bronson, Flatbush Zombies, and Mos Def is suddenly interrupted by something different. A steady four count and then…“Hey girls, B-boys, Superstar DJs- Here we go!” It’s Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three’s The Roof is on Fire. While the straightforward flow and simple beat are a universe away from the sounds I’ve heard during the last hour, there’s something compelling about the three MC’s rocking the crowd and gassing up their DJ. When I close my eyes, the sugaring houses and spruce tree farms of Walden, Vermont disappear and I’m within the sonic universe of the South Bronx forty years ago. After four minutes of steady head bobbing, Charlie Prince calls out to the crowd “The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire” and I can’t help but respond with the recorded crowd: “WE DON’T NEED NO WATER, LET THE MOTHERFUCKER BURN” My sister looks up across the living room

dumbfounded, both eyebrows raised. I’m back in quarantine, now awkwardly fidgeting with a stack of papers and trying to avoid eye contact. This contrast between the rhythmic breaks manipulated by early DJs and the dull tranquility of remote learning has been definitive of the last week of class.

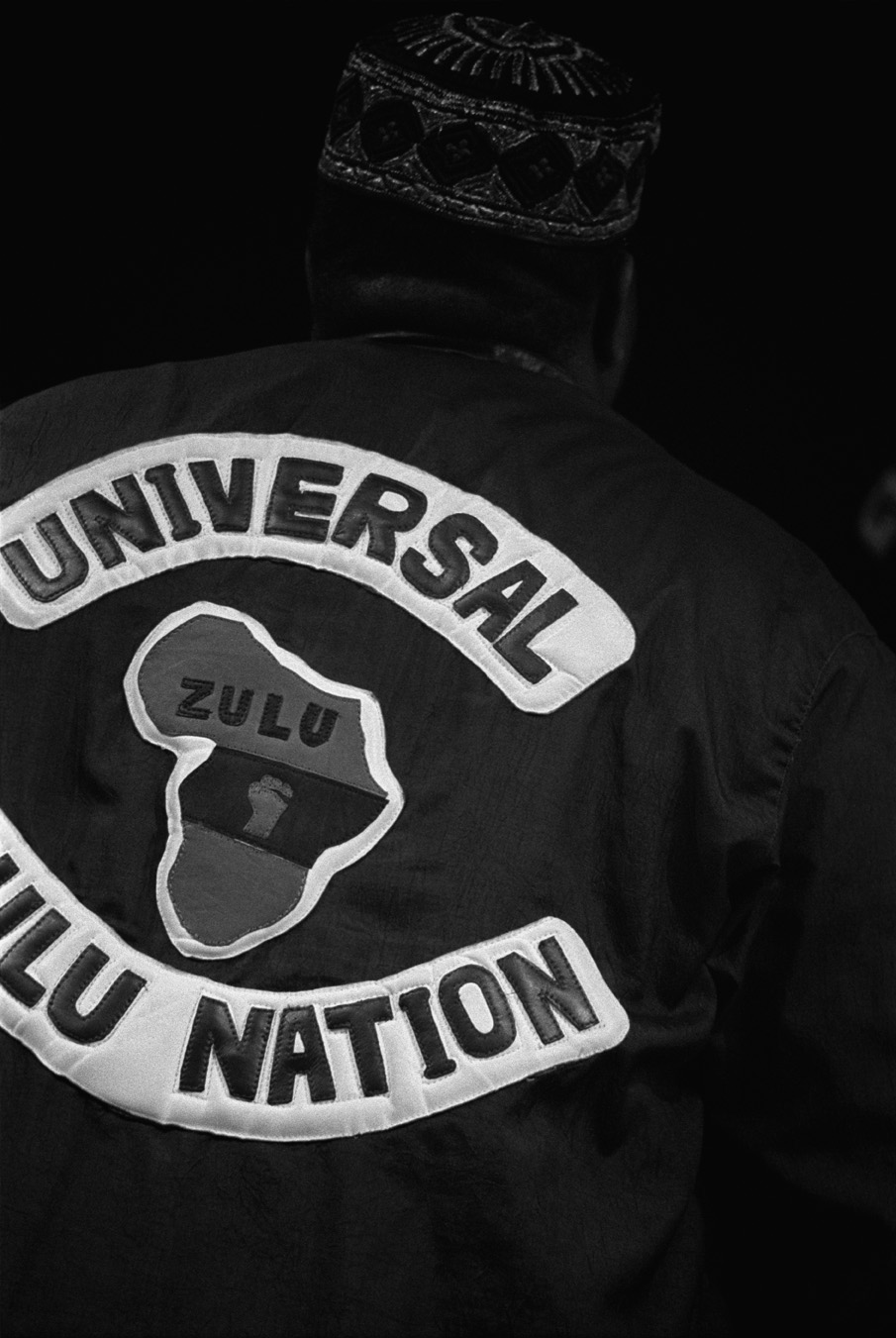

The week began with greetings as well as a short lecture from Dr. Carson about Lil Nas X’s old town road and the politics of genre and charts dating back to the conception of the Billboard Hot 100 (then called the Hit Parade) in 1936. This investigation into the politics of popular music got our collective wheels turning and predicated Wednesday’s discussion of an article by Tricia Rose entitled “Flow, Layering, and Rupture in Post Industrial New York.” This article identified the three elements listed in the title to be the three fundamental elements of Hip-Hop in its core four manifestations (DJing, emceeing, graffiti, and break dancing). In each form, the artists’ abilities to establish rhythm (flow), compound or trump the work of their peers and predecessors (layering), and then breaking from said established rhythm (rupture) worked in harmony to shape the heart of Hip-Hop.

In groups, we then were sent off to investigate each of these four forms and analyze the way each piece incorporated the three elements of hip hop. I found this exercise to be especially eye opening in the way that I view visual art. When looking at a piece by Fab Five Freddy, I was able to see the way in which he transformed a subway car into a mural expressing dissent towards the canonization of protest art movements. What was more enlightening were the parallels drawn between my own analysis of graffiti and my classmate’s respective art forms. The project as a whole painted a holistic picture of Hip-Hop during its genesis.

Thursday was an opportunity for unwinding and expanding our personal playlists as we listened to and discussed our collective class playlist, which you can follow on Spotify! The listening party was demonstrative of our diversity in taste and what allured us all towards one genre. Sharing music allowed us to make connections and even bond over a shared love of artists.

As we transition next week from the Old Skool to the New Skool, I’m excited to learn more about the musicians I grew up listening to and further understanding their cultural implications.