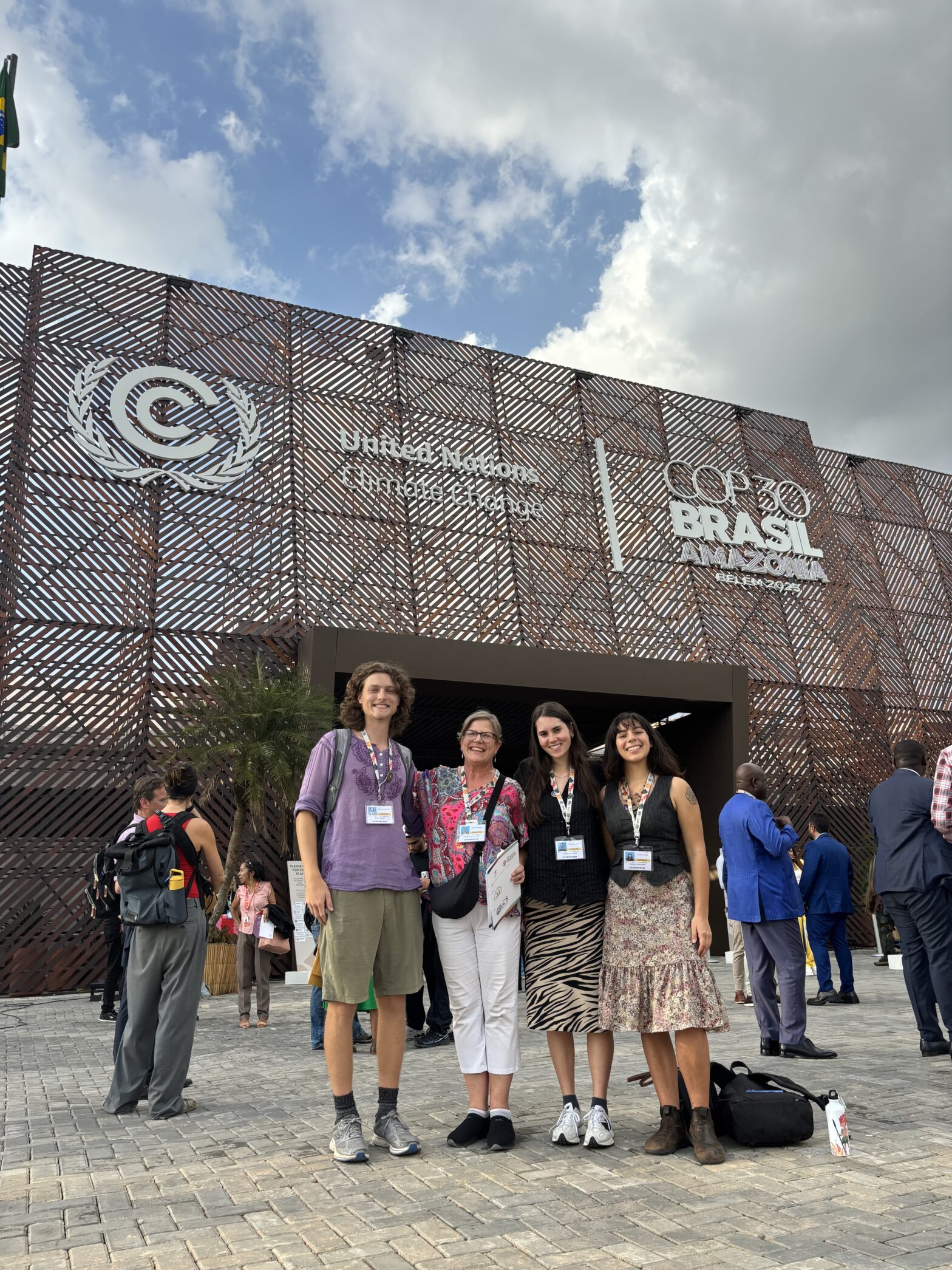

Join the Colorado College Delegation again for a front-row seat to the UN Climate Summit at the “gateway to the Amazon.”

Once again, I am headed to the UN Climate Summit, this time, in Belém, Brazil!

I’m beyond excited; not only for the chance to be part of this global conference once more, but also to experience it with a deeper understanding of how it all works after attending last year. I can’t wait to see the differences and what new challenges and conversations emerge this time around.

This blog was also written for my personal, daily blog providing on the ground insights and updates. Please follow if interested!

This introductory blog is a bit lengthy to cover the bases of the lead up to COP30. Here are the sections to guide your reading/if you don’t want to read it all:

- Why Belem, Brazil?

- Challenges and controversies of the host location

- The absence of the United States from COP30

- What’s at stake for COP30?

Why Belém, Brazil?

We are headed to the Amazon! The Brazilian Presidency (a committee of leaders who run and oversee the entire conference) actually sent an email to delegates announcing a shift in attire requirements from business to “smart casual” due to the high temperatures and humidity.

Belem Brazil is considered the “gateway to the Amazon.” The city is situated on the Amazon River Delta, where the Amazon River system meets the Atlantic Ocean.

Each year, the COP hosting responsibility rotates regions, and within that region, countries bid to host the conference. This year, the conference host region rotated to Latin America and the Caribbean, and Brazil got the nomination to host. Brazil then adamantly chose to host the conference in Belem, as a strategic move to highlight the importance of protecting the Amazon ecosystem by bringing delegates to it physically.

As the largest tropical forest in the world, the Amazon soaks up masses of planet-warming greenhouse gases, making it crucial in the fight against climate change.

However, this location choice has come with much controversy and challenges from elements like housing, price of travel, and the ethics around building a conference venue near the Amazon.

Controversy and Challenges of the Venue:

Housing:

The city typically has around 18,000 hotel rooms but is expecting roughly 50,000 people.

As delegates compete for beds, rates have spiked and some developing countries and non-profits say they are being priced out of the summit.

Price gouging tends to be an issue at every COP, regardless of location, but this year in Belém it’s been especially difficult to secure accommodations due to the city’s limited hospitality infrastructure. The situation has been so challenging that some countries even urged Brazil to relocate the conference to another city.

Organizers have had to get inventive; repurposing “love” motels typically used by couples, river ferries, and even school classrooms to house attendees.

The idea of diplomats, scientists, and climate activists being asked to identify which erotic elements they’d like removed from their rooms is both absurd and unintentionally comical.

Our delegation is staying in an apartment, which has most likely been vacated by the residents for the two weeks we have booked it from, because it is such a lucrative opportunity.

Destruction to the Amazon:

Additionally, a huge hotpoint leading up to COP30 has been the destruction to the Amazon Rainforest with the construction of the conference center.

For COP30, construction is underway on a new four-lane highway that will cut through tens of thousands of acres of protected Amazon rainforest near Belém. The project is intended to ease congestion as the city prepares to welcome over 50,000 attendees.

Critics argue that clearing forest in one of the planet’s most crucial carbon sinks directly undermines the goals of a climate conference and the very point Brazil pushed to host it in Belém.

The irony- or rather hypocrisy- of hosting the conference near the Amazon to catalyze its protection has also been overshadowed by Brazil’s decision to approve exploratory oil drilling at the mouth of the Amazon River in October.

The elephant in the room… or rather absent from the room: US absence

A major force shaping this COP is the absence of the United States…again. Yet that doesn’t mean the country’s influence won’t be felt.

The morning my class left for COP29 in Baku last year, the results of the 2024 U.S. election were announced: Donald Trump had been elected president once more. That news immediately shifted the tone of the conference. The United States’ participation at COP29 was overshadowed by the looming reality of another withdrawal from Paris Agreement U.S. diplomats we spoke with explained how difficult it was to negotiate or secure meaningful commitments when other countries knew the U.S. would soon pull out of the accords for the next four years.

Still, we met with members of the U.S. Delegation and several state-level leaders who expressed optimism that the federal government’s retreat might actually fuel a resurgence of “subnational” climate action. In other words, state and local governments, along with non-governmental organizations, were prepared to step up and fill the gap left by Washington.

When Trump first withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement in 2017, a coalition called We Are Still In emerged in response; a network of cities, states, businesses, and communities committed to upholding the country’s climate goals. That same coalition is reappearing at COP30 in the official delegation’s absence. Over 100 US leaders are expected to attend, representing the country’s ongoing climate efforts from outside the federal sphere.

While no other nations have withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, Washington’s abrupt policy reversals have undeniably dampened global momentum.

The current administration’s focus on fossil fuels over clean energy has reduced incentives for other countries to set ambitious emissions targets through 2035. At the same time, the U.S. has distanced itself from formal climate negotiations while continues to pressure its trading partners to soften or abandon their own climate pledges.

For instance, in recent months President Trump has struck deals with the European Union to purchase $750 billion worth of American oil and gas, and with Japan and South Korea to collaborate on developing rare earth resources, nuclear energy, and fossil fuel projects.

Some analysts suggest that, in the U.S.’s absence, China, the world’s largest emitter, along with the European Union, may seek to assume a more prominent leadership role at the talks.

It will be fascinating to see how the elephant absent from the room continues to shape the conversations, negotiations, and outcomes of COP30.

What is at Stake at COP30?

At COP21 in 2015, under the Paris Agreement, nations committed to significantly cutting global greenhouse gas emissions in order to keep the rise in average global temperatures well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while striving to limit warming to 1.5°C.

Leading up to COP30, a new report, The Global Tipping Points Report 2025 confirmed that global warming is well underway to exceed 1.5°C.

In fact, global temperatures did exceed the dreaded 1.5C mark last year – the hottest year on record.

What does this temperature rise mean?

Exceeding 1.5°C has the potential to trigger multiple climate tipping points, such as breakdowns of major ocean circulation systems, abrupt thawing of boreal permafrost, and collapse of tropical coral reef systems, with abrupt, irreversible, and dangerous impacts for humanity.

In his opening letter to the delegations coming to Belem, the COP30 President, André Corrêa do Lago, acknowledges “the world has entered a new reality,” a “danger zone,” as the window for limiting warming 1.5°C rapid closes.

Yet, he also emphasizes in the letter that maintaining the 1.5°C goal remains at the heart of the COP30 challenge, arguing that “the same science that alerts us to the risks also reveals pathways to hope.” He highlights the potential for “positive tipping points,” where technological, behavioral, and social shifts can accelerate progress toward a low-carbon, climate-resilient future, citing the falling costs of renewable energy as one such example.

The 3 “F’s”: Fossil Fuels, Finance, and Forests:

Fossil Fuels/Emissions:

At this COP, all countries are due to deliver new national climate plans, known as “nationally determined contributions,”or “NDCs.” These are submitted every 5 years and detail countries’ plans to slash emissions and build resilience to climate impacts over the next decade.

Sixty-five countries have formally submitted NDCs as of Oct. 27 — and the current plans fall far short of what’s needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals. They only show about a 17% reduction in emissions from their 2019 levels.

As the COP30 President wrote, these NDC commitments submitted so far reveal a “sobering picture.”

However, countries representing 64% of global emissions still have not formally submitted new NDCs, perhaps leaving room for hope.

Finance:

On the finance front, leaders set a target last year to mobilize $1.3 trillion annually from all international sources for developing countries’ climate action by 2035. That was disappointingly undershot– countries left COP29 with the agreement to mobilize only $300 billion of that goal.

Therefore, at COP30, negotiations will hopefully revisit this finance goal, and mobilize countries to work together to deliver finance for climate mitigation (lowering emissions and global warming), adaptation (financing for adapting to climate changes that are to come), and loss and damage (finance for countries already facing climate change damages) at that scale.

Forests:

In line with the symbolic choice of hosting the conference at the “gateway to the Amazon,” the Brazilian Presidency is placing deforestation and the preservation of the world’s forests at the forefront of the agenda.

The Brazilian COP30 presidency also formally launched the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), a mechanism to provide long-term, predictable financing to countries that protect and sustainably manage their tropical forests.

The goal is to raise $125 billion for the TFFF and already, over 50 countries have expressed support for the initiative. Initial contributions have already come from Brazil, Indonesia, Norway, and Portugal.

Personal Updates leading to COP30:

As for me, I’m approaching COP30 one year older — now a senior on the verge of graduation and preparing to find my place in the professional world. Or rather, my further position within climate work.

Last month, I had the privilege of spending two weeks at National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C. for the pioneer Career Catalyst Block, where the spark within me to pursue a path at the intersection of impact storytelling, science, and education truly ignited. I’m thrilled to reconnect with some of the incredible people I met there at COP30 and to see how their work takes shape in this global setting.

I’m also eager to meet other climate journalists, storytellers, and communicators, and to continue my research into the intersection of gender and global climate negotiations.

And, of course, I can’t wait to experience Belém; its culture, its energy, and its piece of the Amazon.

I left COP29 last year with knots of gripping emotions, grief, anxiety, fear, and overwhelm, as I tried to process the layers upon layers of realities unfolding, and yet to unfold, from the climate crisis. I also carried a heavy sense of guilt; of returning home to the systems of consumerism and environmental degradation that shape my daily, first-world life. And amid it all, I left feeling confused and conflicted about hope.

I don’t believe all action is futile, or that this conference is futile; not in the slightest. Nor do I think hope is futile- it’s vital. But I’ve learned that hope doesn’t mean blind optimism; it’s a grounded persistence, a deliberate choice to act even when the odds feel impossible.

That’s what I’m bringing with me to COP30; a steadier kind of hope, one that makes space for grief and fear but refuses to stop at them.

In his opening address at COP30 today, President Lula of Brazil, warned that “climate change is not a threat to the future – it is a tragedy of the present.”

His words echo the reality we all face; and the urgency of finding meaning, momentum, and moral clarity within that tragedy.

So here we go — into the heart of the Amazon, carrying both the weight of what’s at stake and the quiet, stubborn hope that change is still possible.