Imagine if someone came up and told you that for years there has been a nuclear weapons plant leaking radioactive waste into your backyard, and until right now, you had no idea. How would you react? If the air you breathe, the soil used to grow your vegetables, and the water you drink on a daily basis was contaminated by hazardous waste leaking from a secret plant just down the street? Would you be angry? Scared? Imagine the questions you would want to ask, the panic you would feel, and the injustice of the situation.

This realization became a reality for residents living near and working at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons plant in 1992, three years after the FBI, the Justice Department and the EPA raided the plant to investigate allegations of the environmental crimes. The plant, located on a plateau just outside Arvada, CO, produced nuclear weapons triggers, called pits, for almost forty years without anyone knowing about it. The US government protected the plant’s secrecy on the premise of preserving national security, while plant workers and nearby residents were unknowingly exposed to hazardous radioactive material.

This raises a few critical questions. Why were these hazards sited close to this community? And why they were expected to bear the environmental and health burdens for the benefit of our national security? Why was the public so misinformed and excluded from the decision-making process about the environmental risks taking place in their own backyard?

This raises a few critical questions. Why were these hazards sited close to this community? And why they were expected to bear the environmental and health burdens for the benefit of our national security? Why was the public so misinformed and excluded from the decision-making process about the environmental risks taking place in their own backyard?

The decision to conceal information about the hazards and risks related to contact with radioactive material at the plant violates principles of environmental justice. People have the right to know if they are being exposed to radioactive material, and trust the government to tell them if they are in any danger. Yet, prior to 1992, nearby residents thought that the Rocky Flats Plant produced “cleaning supplies” and “scrubbing bubbles” (Iversen 2016, 12). To this day, people who worked at the plant are still unaware of what they produced and the chemicals they interacted with. By withholding information about the production of nuclear weapons, the affected group was unable to make an informed decision about whether or not to stay in the contaminated neighborhood.

In 1990, when scientist Carl Johnson released findings that exposed alarming levels of contamination being emitted from the Rocky Flats plant, the government used the media to hide the truth; the presence of, and risks associated with plutonium in the area. Johnson’s article was ridiculed in the press as being “largely useless” and “running the risk of being a cruel joke” (Iversen 2016, 131). Fearing that environmental and health concerns would halt plant production, the government found it justifiable to withhold information about these risks. Ultimately, the decision to leave the public uninformed violated the risk assessment that workers and residents were able to make about their safety.

Despite the plant’s official closing in 1992, individuals experiencing negative health impacts as a result of unknown exposure to plutonium still struggle to receive monetary compensation from the government. Janet Brown, a former Rocky Flats Plant employee, developed epilepsy after years of working at the plant. She also knows other former employees who suffer from “Parkinson’s disease, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, and diseases that affect the immune system, like lupus” after working at the plant for many years (Brown 1957, 12). She explained how Rocky Flats Plant “promised that if we were ever to become ill, we would never have to pay any medical benefits. If we were on disability, then our medical benefits would always be free” (Brown 1957, 13). But the government hasn’t followed through on its promise. As more workers developed disabilities stemming from radiation and chemical exposure from the plant, the government changed its policy. Brown explained that if you wanted to keep your medical benefits, “you had to pay for them unless you could prove direct discriminatory intent,” which proved very difficult (Brown 1957, 13).

Environmental injustice occurred at Rocky Flats in the disproportionate distribution of environmental burdens to a targeted group of people. Plant workers and nearby residents did not voluntarily assume the risks associated with proximity to the radioactive material because they were unaware of its existence. Procedural justice was lacking in the initial decision-making process of the facility, which made it easy to continue to exclude the affected group in conversations about the plant’s safety regulations and compensation benefits for the harms caused when it was shut down.

I would like to report that the situation at Rocky Flats has improved. That nearby residents are being told about the dangers of the plutonium, that proper clean up has taken place, and that areas still contaminated by radioactive waste have been shut off to the public. But that is not the case.

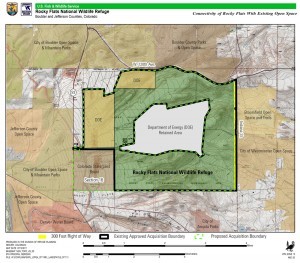

Initial estimates for proper clean up of the Rocky Flats area estimated 70 years and $36 billion, but the company selected to remediate the site completed the job in less than 10 years and for $7 billion (Nordhaus 2009, 6). Due to a lack of sufficient cleanup, plutonium levels in the area remain too high for safe public interaction. Yet in 2007, the US Fish and Wildlife Service established the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge on contaminated Rocky Flats land. The Refuge spans over 5,000 acres and has eight miles of hiking trails open to the public, without a word about the remaining presence of radioactive waste that remains on the site of the old nuclear plant.

Sources:

Sources:

- Iversen, Kristen. Full Body Burden. Vintage, 2016.

- Brown, Janet. “Brown, Janet.” Dorothy D. Ciarlo. Rocky Flats Oral History Collection.1998.

- Nordhaus, Hannah. “The Half-life of Memory: The struggle to remember the nuclear West.” High County News. 17 February 2009.

Further Reading:

- Brulle, Robert J., and David N. Pellow. “Environmental justice: human health and environmental inequalities.” Annu. Rev. Public Health 27 (2006): 103-124.

- Bryner, Gary C. “Assessing claims of environmental justice: conceptual frameworks.” Justice and natural resources: Concepts, strategies, and applications (2002): 31- 56.

- DeMayo, Eugene F. “DeMayo, Eugene F.” Dorothy D. Ciarlo. Rocky Flats Oral History Collection, 1956.

- Fiorino, Daniel J. “Citizen participation and environmental risk: A survey of..” Science, Technology & Human Values 15, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 226.

- Grossman, Charles M., Rudi H. Nussbaum, and Fred D. Nussbaum. “Cancers among Residents Downwind of the Hanford, Washington, Plutonium Production Site.” Archives Of Environmental Health 58, no. 5 (May 2003): 267-274.

- H.L.A. Hart. The Concept of Law (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1961), 162.

- Rawls, John. “Distributive justice.” Perspectives In Bus Ethics Sie 3E (1967): 48.

- Risk Assessment Corporation. Final Report: Technical Project Summary. Radionuclide

- Soil Action Level Oversight Panel. February 2000.

- Robbins, Paul, John Hintz, and Sarah A. Moore. Environment and society: a critical introduction. Vol. 13. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.