By Esra Siddeek

COlorado COllege Class of 2017

Introduction

“…[environmental justice] means the fair treatment of people of all races, cultures, and incomes with respect to the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”[4]

This is the statement given by the state of California in regards to defining environmental justice. One example of this type of environmental injustice are the residents of Lindsay who have been experiencing health problems during the peak spraying seasons of the pesticide chlorpyrifos on orange groves.[3],[7]

![Residents of Lindsay, California protest against pesticide air contamination. [3]](https://sites.coloradocollege.edu/ejsw/files/2016/11/protestlindsay.png)

Residents of Lindsay, California protest against pesticide air contamination. [3]

Therefore, Tulare County should construct buffering zones, especially in areas between schools and sites of chlorpyrifos use. Furthermore, adequate information regarding how to avoid exposure should be provided for the parents and guardians of affected children. This blog will first examine the effects of chlorpyrifos on humans, particularly children, the case study performed in Lindsay, the effect of the lack of public participation, and how environmental justice has not been met in relation to Title VI.

Properties/Health Effects of Chlorpyrifos

Chlorpyrifos is a type of insecticide used mainly on oranges, cotton, corn and several different crops.[7] Chlorpyrifos has been known to affect both insect and mammal nervous systems by inhibiting an enzyme Additionally, a loss of this enzyme can cause symptoms related to motor damage such as drooling and muscle twitches. More serious exposure can lead to breathing impairment and paralysis.[1]

Lindsay Case Study

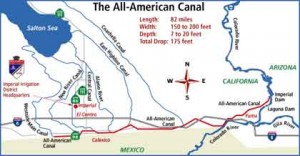

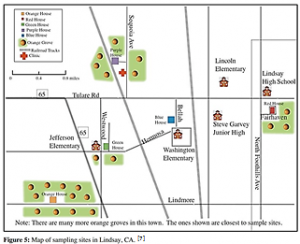

A case study in 1996 was conducted by the California Air Resources Board (ARB) in conjunction to the California Toxic Air Contamination act to monitor the chlorpyrifos use on an orange grove in Tulare County. It was found that there were high risks of exposure directly next to the application sites and in high use areas. Within Lindsay, there are five schools located near orange groves with chlorpyrifos application.[7] Of these schools, three are elementary. 95% of the samples collected were above the Reference Exposure Level (REL) for both children and adults. REL refers to the amount of airborne toxin an individual can be exposed to without adverse health effects.[8]

A case study in 1996 was conducted by the California Air Resources Board (ARB) in conjunction to the California Toxic Air Contamination act to monitor the chlorpyrifos use on an orange grove in Tulare County. It was found that there were high risks of exposure directly next to the application sites and in high use areas. Within Lindsay, there are five schools located near orange groves with chlorpyrifos application.[7] Of these schools, three are elementary. 95% of the samples collected were above the Reference Exposure Level (REL) for both children and adults. REL refers to the amount of airborne toxin an individual can be exposed to without adverse health effects.[8]

Public Participation Framework

Tulare County California consists of approximately 82% people of color living in Disadvantaged, Unincorporated Communities (DUCs)[5] because of the years of exclusion from the decision-making processes regarding land use and communal investments. Residents in DUCs often do not have the necessities for healthy living environments such as clean water and sewer systems.[9] Since people, such as in the town of Lindsay, living in DUCs are struggling to be heard and having input in the decision-making processes of such policies, the state of California has failed to address the frameworks of public participation outlined in their policy.[4]

Pesticide Use and Title VI

Title VI was initially a part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and describes the policy of preventing discrimination based on “race, color, or national origin” in participation of programs that require federal assistance in terms of finances. Over the years, Title VI has been adapted to encompass “impact” of burdens due to racial disparity.[2] Using Title VI in attempt to address the issue of impact on environmental resources has been proven to be complicated. In 2000, the U.S. EPA published a guide in defining the impact of environmental justice issues in the context of Title VI as, “negative or harmful effect on a receptor resulting from exposure to a stressor.” “Receptor” in the context of the quote refers to the individuals and/or groups encountering the problem.[10]

Like other communities in Tulare County, Lindsay has several individuals who cannot afford the cost of treatment necessary for chlorpyrifos poisoning. According to Javier Huerta, a resident of Lindsay:

“I have health problems and the doctor for the study told me that these might be related to exposures. The income of my family is low and I don’t have resources to go to the doctors. I have to choose between feeding my family or taking them to the doctor when pesticides seem to be making them ill.”[6]

As a result, Lindsay residents like Huerta are forced to manage their child’s symptoms on their own and thus cannot provide the necessary documentation to pursue a case in environmental justice despite the clear articulation of Title VI.

Conclusions

As discussed, residents of Lindsay, California come from predominantly low income communities and DUCs and have little input into environmental policies. This lack of public participation is one of the main reasons for why chlorpyrifos is so poorly regulated in Lindsay, which thus constitutes environmental injustice. An example mentioned earlier is the lack of enforcement in the notification to nearby schools regarding application. Moreover, stronger regulations need to be put into place regarding the agricultural use of chlorpyrifos. In addition to the suggested construction of buffer zones between sites of application and nearby schools, information should be readily accessible to the public in regard to preventing exposure. Lastly, research should be conducted on finding alternative methods of protecting crops without the use of pesticides.

Keywords: Tulare County, U.S. EPA, chlorpyrifos, DUCs, Title VI, Lindsay California, California ARB, AB 947

Follow other pesticide issues on Twitter! #pesticides

Further Readings

- Christensen, K., Harper, B., Luukinen, B., Buhl, K., and Stone, D. Chlorpyrifos General Fact Sheet. National Pesticide Information Center, Oregon State University Extension Services, 2009. Web.

- Cole, L. W. “Expanding Civil Rights Protections in Contested Terrain.” Justice and Natural Resources: Concepts, Strategies, and Applications. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2002. 187-208. Print.

- DeAnda, T. Airborne Poisons: Pesticides in Our Air and in Our Bodies. Tulare County: Californians for Pesticide Reform, 2007. Print.

- Order No. 12898, 3 C.F.R. (1994). Print.

- Flegal, C., Solana R., Jake M., and Jennifer T. California Unincorporated: Mapping Disadvantaged Communities in the San Joaquin Valley. Rep. PolicyLink. California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc. and California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, 2013. Web.

- Huerta, J. Interview. Airborne Poisons: Pesticides in Our Air and in Our Bodies May 2007. Californians for Pesticide Reform. Web.

- Mills, K., and S. Kegley. Air Monitoring for Chlorpyrifos in Lindsay, California June–July 2004 and July–August 2005. Pesticide Action Network North America, 2006. Web.

- “Notice of Adoption of 12 Chronic Reference Exposure Levels (RELs) for Airborne Toxicants, Dec 2001.” OEHHA Science for a Healthy California. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 28 Dec. 2001. Web.

- The Community Equity Initiative. San Francisco: California Rural Legal Assistance, 2012. Print.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Draft Revised Guidance for Investigating Title VI Administrative Complaints Challenging Permits. 2000. Print.