By Zach Holman

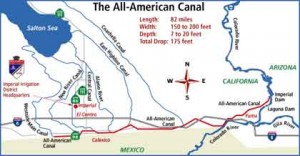

The United States federal government has been notorious for committing environmental injustices within the border of the country since its inception. By lining the All-American Canal (AAC) the U.S. pushed an injustice across their southern border to the Mexicali region in Mexico. In 2009 Parsons Corporation — commissioned by the United States Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) — completed the concreted lining of the All-American Canal. They only lined a 23-mile section of the 82-mile long canal that is fed from the Colorado River starting in Yuma, Arizona. It was highly contested by many groups. The canal was an important water source for the people of the Mexicali Region in Mexico who live just south of the U.S. border where the canal runs. A coalition formed between a few groups and sued the U.S. federal government in hopes of stopping the construction. The groups were the Mexican government, two U.S. environmental groups and the town of Calexico.3

The lining of the AAC was contested because when it was completed in the 1942 it was not lined and therefore over 67,700 acre-feet were lost to seepage each year. This may sound like a bad thing and that the U.S. should have lined it immediately with concrete to fix this, but the seepage became necessary to the Mexicali region. The seepage ran underground and recharged aquifers across the border. The Mexicali citizens used this water to fuel an agricultural industry and supply the people with drinking water.3 They had been using this water since the original canal was constructed. So, when the U.S. announced they would line a 23-mile long section the Mexicali people were outraged. “We were using this water for over 100 years and we developed the economy that depends on the seepage,” Rene Acuna, a Mexicali civic leader, explains.2

As the definition that this blog uses for environmental justice describes that the injustice must fall upon disempowered people, the Mexicali and Calexico citizens fall under this category. The Mexicali people are far more impoverished than the citizens of San Diego County (where the water was diverted to) and they do not have the ability to fight adequately to prevent the injustice. Calexico is a town in California on the border that relied on business from Mexicali for its entire economy.4 It was a crucial shopping center for the Mexicali people.2 The Calexico citizens realized if the AAC was lined that the Mexicali economy would collapse and therefore people could not shop in Calexico. The people of Calexico are mostly Hispanic and impoverished. This qualifies them under the umbrella of environmental justice due to an action by the federal government. These two groups of people, the Mexicali and Calexico citizens, filed a lawsuit along with two environmental groups against the U.S. government and the case was heard in the Ninth District court.

The case was based on a few injustices. The first, argued by the environmental groups, was that wetlands would dry up and these wetlands were necessary for certain migratory birds. There is a U.S. law that states that if development is going to occur that harms habitats a full review must first take place. The required review did not happen. The second basis for the case was that there is a 1973 treaty that is part of the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) between the U.S and Mexico that states if one of the countries is going to do development on surface or ground water the other country must be adequately consulted first. The Mexicali government, along with Calexico, said that the U.S. government did not adequately fulfill this agreement. The U.S only allegedly paid lip service to the Mexicali government.5

This obviously does not sound like anything new in U.S. history. A treaty is agreed upon and then is never held up by the U.S. It is a sad truth, but happens all, and I mean all, the time. The Ninth district court ruled in favor of the U.S. and as stated earlier awarded Parsons Corporation the contract and gave the go-ahead on the project.1

The lining is clearly an environmental justice issue. The people who were affected most are disempowered populations that do not have options for fixing the problem. They cannot just find a new water source and the water that remains in the aquifer is becoming dangerously salinized as there is not a constant source of fresh water to dilute it. In the framework of environmental justice, reparations should be made toward the Mexicali and Calexico people. What remedy would be just, though? Is money enough to offset a lack of water? These questions need to be asked by the U.S. government; the only problem is the court did not rule that the U.S had any responsibility to the groups affected. This means those questions were not asked and the people were left high and dry, most literally.

Keywords

All-American Canal, US-Mexico Border , Environmental Justice, Calexico, Mexicali, Colorado River, USBR, Water

Sources

- “All-American Canal.” All-American Canal. Parsons, 2008. Web. 04 Nov. 2016.

- Boxall, Bettina. “Suit Is Filed Over Plan to Line Canal.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 20 July 2005. Web. 03 Nov. 2016.

- Cortez-Lara, Alfonso, and Maria Rosa Garcia-Acevedo. “The Lining of the All-American Canal: The Forgotten Voices.” Natural Resources Journal40, no. 2 (March 15, 2000): 261. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed October 26, 2016).

- Cortez Lara, Alfonso A., Megan K. Donovan, and Scott Whiteford. “The All-American Canal Lining Dispute: An American Resolution over Mexican Groundwater Rights?.” Frontera Norte21, no. 41 (January 2009): 127-150. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed October 26, 2016).

- Ries, Nicole. “The (Almost) Ail-American Canal: Consejo de Desarrollo Economico de Mexicali v. United States and the Pursuit of Environmental Justice in Transboundary Resource Management.” Ecology Law Quarterly35, no. 3 (August 2008): 491-529. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed October 26, 2016).

- Perry, Tony. “Officials Hail $300-million Project to Line Leaky All-American Canal.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 1 May 2009. Web. 04 Nov. 2016.