Introduction

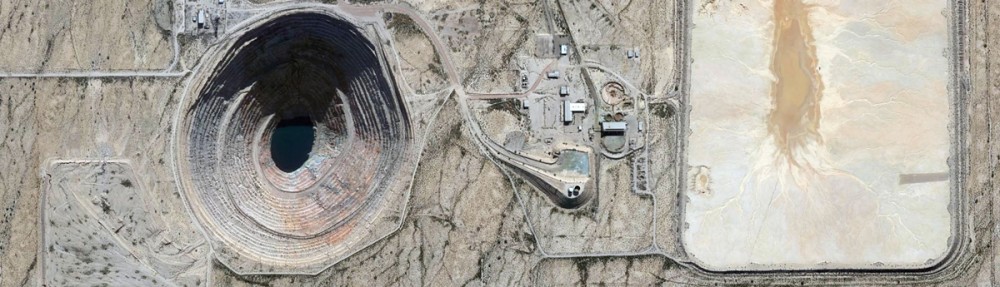

After initial permitting in 1994, an American company called Dos Republicas Coal Partnership hired Camino Real Fuels LLC to begin mining for coal in late 2015 in an overwhelmingly poor, Hispanic, and Native American community near the town of Eagle Pass in Texas.(1) The 2.7 million tons(2) of low-grade “bituminous” coal being mined every year is of such poor quality it is illegal to burn in the United States, so it is being sold to Mexico’s Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), a government-owned electricity provider. CFE burns the coal half an hour south of Eagle Pass in Nava, Mexico, at one of the two most polluting power plants in North America. The plant is close enough to the border that the air leaving the facility further pollutes Eagle Pass. The pollution from both the mine and the plant endangers the water and air quality of the region(3) and poses a threat to the hundred historical Native American sites belonging to the tribes in the area, which include Carrizo, Comanche, Coahuiltecan, Cherokee, Kickapoo, Xicano, Apache, and more.

Eagle Pass Mine is a textbook example of an environmental injustice; it is an extraction of a natural resource that disproportionately hurts minorities and the poor. More specifically, it affects the many tribes in the area more than anyone else, as it hurts their sacred connections with the land. There is no set definition of environmental justice. Texas is part of EPA’s Region Six, which has its own definition. This case study uses that definition to evaluate the environmental injustice of the Eagle Pass Mine by walking through the ways in which Executive Order 12898 was broken.

Executive Order 12898

In 1994 President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, which expressed the need for environmental justice. He ordered that each federal agency create a strategy to work towards environmental justice, following four specific guidelines:

1) To help promote health and environmental statutes already in place in disadvantaged areas.

2) To ensure community participation in decisions.

3) To conduct thorough research relating to the health and environmental impacts of minority and low-income populations.

4) To determine any disproportionality in which groups benefit from environmental developments, then outline steps to address disparity.

Initial permitting for this project took place in 1992, two years before this executive order. However, permits granted in 2006, 2011, and 2015 by the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality (TCEQ), the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and the Texas Railroad Commission insufficiently addressed parts two, three, and four of this framework thus failing to fulfill President Bill Clinton’s executive order.

Public Participation

The Eagle Pass community is and was unanimously against the Eagle Pass Mine. 45% more residents signed a petition against the mine than the amount of residents who voted in the 2012 election.(4) Between 1994 and the mine’s first extraction in 2015, community members presented their opposition to the USACE(5), they fought permits in various courts(6), and finally, they resorted to peaceful protest.

(Indigenous peoples and other community members opposed to the Eagle Pass Mine walk nine miles in protest. These photographs were taken by Kin Man Hui and posted on Express News.)

In a phone interview on November 11th, self proclaimed “American face” of Dos Republicas Rudy Rodriguez described his company’s community engagement, which included going to little league games. When asked how he took into account the needs of the indigenous peoples of Eagles Pass, he responded, “I helped the Kickapoo tribe… Twenty years ago one summer when they were out there working to push the Secretary of Interior for a casino that they have… That’s the tribe that’s there.” In reality, that is one of the over seven tribes that are there – none others of which he could name. He then asserted, “We respect everybody’s position in terms of freedom of speech and what not,” and went on to describe permitting that amounted to “ten to twelve feet high in paper.”(7)

Sufficient Environmental and Social Research

While describing environmental considerations and permits, Rodriguez used the phrase “above and beyond” five times. Though North American Coal Corporations did research on the health and environmental impacts of the coalmine, they did not perform it in regards to minority or low-income communities. When the EPA did their own analysis this year, they discovered that NA Coal’s research was insufficient and that in reality the Eagle Pass Mine is not up to environmental standards.(8) On top of the mine’s environmental degradation, the effects of the air pollution from the power plant just down the road in Mexico is still entirely unknown.

Disproportional Benefits and Burdens

The EPA, the TCEQ, and the USACE did no research on how this project might disproportionately harm or advantage groups of people. As a result, the Native American peoples of the Eagle Pass area are bearing a disproportionate amount of the burden for a project that does not benefit them.

Juan Mancias is an outspoken member of the Eagle Pass Corrizo Tribe. After coal mining commenced in Eagle Pass late last year, he publicly demanded answers to how such a clear injustice could continue. In a phone interview on November 3rd, 2016, he expressed his cultural qualms with the construction of the Eagle Pass Mine: “Our creator came to the Earth…” he explained, “She is our mother.” “There is a time people were hurting each other, becoming very greedy… She listened to the voices of the people who were hurting… We take care of the beauty she has created.” He said the site of the Eagle Pass Mine used to be one in which eagles and ravens would fly to express this beauty. “When they opened this mine up again, they let all these feelings back out.” Regardless of the health impacts, the implementation of the Eagle Pass Mine hurt the sacred connections that people like Mancias had with the area. When asked what other tribes were affected, he responded “All of them.”(9) The Eagle Pass mine is a clear environmental injustice to the many indigenous peoples of the Eagle Pass region.

Conclusion

Region Six of the EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” In the case of the Eagle Pass Mine, the indigenous peoples of Eagle Pass are burdened disproportionately by mining operations and were not given the opportunity to have meaningful involvement in the implementation process. This environmental injustice is a direct result of the approving government agencies of the mine including the TCEQ and the USACE, and their disregard for the steps set out in executive order 12898. The permitting process did not include public participation, adequate research on health and environmental concerns and their disproportionate affects, or proper analysis of whom the Eagle Pass Mine would benefit. As a result, Native American peoples suffer from yet another form of cultural genocide and are at risk of a wide array of health risks

Sources and Further Information

1. “A Tale of Two Republics: Native Resistance to Coal Mining in Texas.” Equilibrio Norte. December 18, 2015. Accessed November 04, 2016. https://equilibrionorte.org/2015/12/18/a-tale-of-two-republics-native-resistance-to-coal-mining-in-texas/.

2. Lobet, Ingrid. “In Texas, a Coal Mine Opens to Power Mexico.” Marketplace. August 25, 2015. Accessed November 04, 2016. http://www.marketplace.org/2015/08/25/sustainability/texas-coal-mine-opens-power-mexico.

3. “Project Description.” Dos Republicas Coal Partnership. Accessed November 2, 2016. http://www.dosrepublicas.com/project.html.

4. Lobet, “In Texas, a Coal Mine Opens to Power Mexico.”

5. Https://www.tceq.texas.gov/assets/public/comm_exec/agendas/comm/backup/Proposal-for-Decision/2015-0068-IWD-RTC.pdf. PhD diss., Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 2015. State Bar of Texas.

6. Landa, Jose G. “City of Eagle Pass and Maverick County Party Status Challenged by Dos Republicas Coal Partnership.” Eagle Pass Business Journal. 2015. Accessed November 04, 2016. http://www.epbusinessjournal.com/2015/04/city-of-eagle-pass-and-maverick-county-party-status-challenged-by-dos-republicas-coal-partnership/.

7. Telephone interview by author. November 11, 2016.

8. United States of America. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Fort Worth District. Detailed Comments on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Final Environmental Impact Statement for Surface Coal and Lignite Regional Mining in Multiple Counties in Texas. By Darvin Messer. Fortworth, Texas, 2016.

9. Telephone interview by author. November 3, 2016.

Other Sources and Further Reading

Exec. Order No. 12898, 3 C.F.R. (1994). https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf.

Applicants Response to Hearing Request (Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2011).

“Welcome to the Carrizo/Comcrudo Tribe of Texas.” Carrizo/Comcrudo Tribe of Texas. 2010. http://www.carrizocomecrudonation.com/index.html.

Mancias, Juan, Jonathon Hook, and Angela Pitsai. Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas. Comment. Facebook, 2015. https://m.facebook.com/CarrizoComecrudoTribeOfTexas/posts/1010799335646652.

Turrentine, Jeff. “Environmental Justice: One Texas Man’s Refinery Fight.” NRDC. August 26, 2016. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/environmental-justice-one-texas-mans-refinery-fight.

United States of America. Environmental Protection Agency. Region 6. Border 2020 Goals and Objectives. https://www.epa.gov/border2020.

United States of America. National Environmental Policy Act. https://ceq.doe.gov/welcome.html#Act.

EDF Group’s Reply to Exceptions to the Proposal for the Decision (State Office of Administrative Hearings 2015).