|

|

Office of Sustainability

Enhancing Educational Experiences within the Office of the Dean of the College

|

|

Ditch the Dumpster!

Are you planning your move-out? Ditch the Dumpster is an annual program coordinated by the Office of Sustainability in partnership with Residential Experience. It encourages students to donate their gently used items instead of throwing them away during move-out. Some donated items will go to the CC Pantry Exchange and will be saved for future move-ins. The rest will be distributed to local organizations by the Haseya Advocate Program, a Native woman-led organization that serves Indigenous survivors of domestic and sexual violence in the Colorado Springs, Colorado region. Accepted items include clothing, hangers, unopened food, houseplants, outdoor gear, and small household/dorm items. The program runs from May 15-25 at four collection sites accessible 24/7:

- Loomis Lobby

- South Lobby

- Mathias Lobby

- Hybl Community Center

Leading up to Ditch the Dumpster, you can also drop off accepted items at the CC Exchange. During block 8, the CC Exchange will have extended hours to donate. Open hours of the space during weeks 1-3 will be from 1:00-5:00 p.m. located in the Worner basement for the CC Exchange only (not the CC Pantry).

|

|

|

End Of The Year and Earth Week Recap

|

|

|

The Office of Sustainability extends our sincere gratitude to everyone who played a role in organizing, supporting, and participating in the vibrant and dynamic Earth Week 2023. Earth Week featured a wide range of engaging events, including Arbor Day, Sustainable Wednesdays, and the Linnemann Lecture, all of which were aided by our dedicated students, faculty, and staff. This annual initiative, which is a collaborative effort between the OOS, campus partners, and various student clubs, serves as a powerful vehicle for promoting environmental consciousness and sustainability. Thanks to everyone who contributed their time, energy, and resources to make Earth Week 2023 a huge success and a source of inspiration for all who attended.

As another academic year draws to a close, the Office of Sustainability would like to express our gratitude for the unwavering support and collaboration from our campus partners and the entire student body. With the leadership of Director Ian Johnson, Coordinator Mae Rohrbach and our dedicated intern teams and volunteers, we continue to make CC a model for sustainability. We have successfully facilitated a variety of events, programs, and campaigns that were made possible by the active participation and support from the campus community. Looking ahead, we remain even more committed to building on this progress and forging a sustainable community here at Colorado College.

|

|

Emissions Team Greenhouse Gas Technical Report

The Office of Sustainability’s Emissions Team is excited to announce that the annual Greenhouse Gas Technical Report has been published! You can view the full report here. This report is instrumental in outlining Colorado College’s gross emissions each year and how the college is working toward reducing its impact on the environment. “This year’s emissions figures demonstrate Colorado College’s ongoing commitment to sustainability. We continue to maintain our institutional carbon neutrality,” says Holden Maxfield ’25, Emissions Team member.

|

|

STARS State of Sustainability Report

The 2022-23 State of Sustainability Report is here! The State of Sustainability Report is the Office of Sustainability’s final publication of the year that celebrates and communicates the work our entire community has done each year. Read this year’s report here to learn about the sustainability efforts, projects, and initiatives our office and other members of our community participated in during the 2022-23 academic year. The format of the report this year is a collection of StoryMaps which our Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) intern and volunteers put together during the spring semester. StoryMaps is a software of ArcGIS that engages the audience interactively and compellingly through photos, videos, live links, etc. You can engage with the whole report in chronological order, or you can skip around to different topics you are interested in such as campus operations, planning and administration, academics, etc. Special thanks to STARS intern Hannah Shew ’24 and her volunteers Audra Burrall ’23, Jessie Squires ’26, and Haoru Yang ’24 for all their hard work putting together this report!

“I think the most exciting thing I’ve learned as part of the STARS team is how vast the scope of sustainability really is. Being a part of this team gave me the ability to have a bird’s eye view of the whole process and is a great start to my sustainability journey,” says Squires.

|

|

|

E-Waste Drop-Off Event

E-Waste Block 8 Drop-Off Event

Wednesday, May 17 2:30-4 p.m.

Breton Hall Garage 8

|

|

Do you have electronic waste you want to dispose? Well, the CC Office of Sustainability has a solution for you! We recycle electronic waste. These are items that are no longer working, unwanted, or at the end of their life. Through E-Tech Recyclers, a local Colorado Springs e-waste business, these materials are safely and responsibly recycled. Acceptable and commonly recycled items include TVs, monitors, keyboards, cables, appliances, digital media players, cell phones, and other items. Please note we cannot recycle alkaline batteries, which include most household batteries, like Duracell, Energizer, and others.

Students who can transport their own items are invited to drop off items at Breton Hall Garage 8 on Wednesday, May 17 from 2:30-4 p.m. Please refer to the map above to locate the Breton Hall Garages (the northwest corner of parking lot C-1). Staff will be there to help you unload your items! Faculty and staff who cannot attend this event can fill out this request form for a pick-up, and a representative will be in touch with you about your request within three business days.

*Please note that if your items are both college-issued AND contain a hard drive (laptops, computers, etc.), you must reach out to ITS for them to wipe this hard drive before recycling. Additionally, a pickup option is available ONLY for office/departmental requests. For any personal requests from CC community members, drop-off at the e-waste garage is the only option.*

|

|

Offset Travel Emissions

As summer break quickly approaches, many of us may be planning to travel by plane or car for long commutes home or elsewhere. Air travel and long drives generate excessive carbon emissions that are released into the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. The Office of Sustainability has created a tool to help campus community members reduce our collective carbon footprint. Simply enter your travel details into the Travel Offset Calculator, and then click the “Offset This Trip” button. The price to offset the carbon emissions created by your summer travel is less than the price to travel, and it is an important step towards helping to curb global warming. The Office of Sustainability wishes you a happy and healthy summer break and wants to remind you to practice sustainability wherever and whenever possible!

|

|

CC Student Activist Makes Climate History

For the last Office of Sustainability newsletter of the academic year, Jacob McDougall ’24, an Office of Sustainability Communications Intern, interviewed Rikki Held ’23, who is the named plaintiff in a historic youth-led climate lawsuit against the state of Montana. Held highlights how she is “one of 16 youth plaintiffs in this lawsuit against the Montana state government” which was brought upon by Montana “violating several of [the plaintiff’s] state constitutional rights” such as the right to “a clean and healthful environment.” Held notes that, “the state of Montana supports a fossil fuel-based energy system which contributes to climate change and is harming us. We want Montana’s courts to hold our government accountable so that their actions match what scientists say is needed in order to reduce emissions and protect our constitutional rights and our natural resources.” When asked how Montana’s constitutional declaration to “maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment” been violated, Held conveys that “this fossil fuel-driven energy system is contributing to the climate crisis and harming our natural resources such as our atmosphere, water, and wildlife. Montanan’s experience impacts to our businesses and livelihoods, our physical and mental health, and our environment which we want to conserve for future generations.” Held has personally “experienced impacts to [her] family’s ranch and motel business due to wildfires, drought, water variability, and extreme weather events” and her “health [has] also impacted by extreme heat and wildfire smoke.”

Held’s lawsuit is the first youth climate lawsuit to go to trial in U.S. history. She recognizes the importance of youth leadership in addressing climate change and advocating for environmental justice when she draws attention to how “young people have powerful voices and stories that need to be shared with decision-makers, like judges, and we can certainly make a difference, especially as we will experience the worst of climate impacts and cannot keep passing this problem on for future generations to solve,” says Held. “We need perspectives from all ages and backgrounds to solve this issue.”

With Held set to graduate this May, she portrays how her time at Colorado College has impacted her journey. “I joined this lawsuit halfway through my first year of college and have certainly grown with it and changed since then,” says Held. The block plan has allowed her to take “pieces from all [her] courses and experiences from learning about earth systems and people within our environment to practicing scientific communication has strengthened [her] ability to be a part of this lawsuit and pursue a career in the sciences to help people and the places in which we live.” Lastly, she wishes to depart CC with this powerful message for the campus community:

“I have greatly appreciated the people here and my time here at Colorado College and I know my fellow classmates and I will take what we’ve learned and apply our values into what we all pursue beyond college as well. We can make a change in whatever we decide to dedicate ourselves to no matter what paths we follow using our knowledge, creativity, empathy, and values.”

For more information regarding Held’s historic climate lawsuit, you can view this recently published Vice News video featuring Held and another plaintiff.

|

|

|

|

|

|

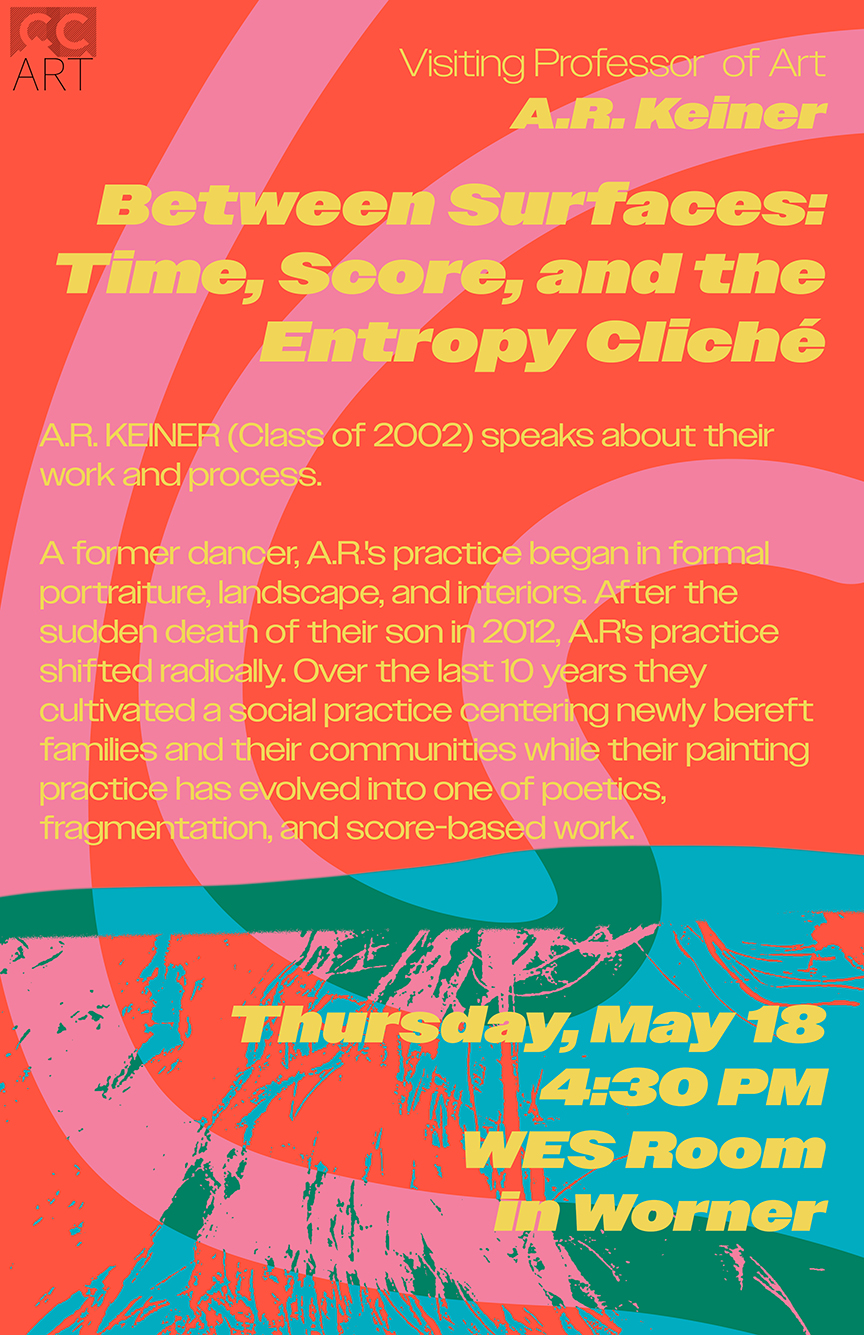

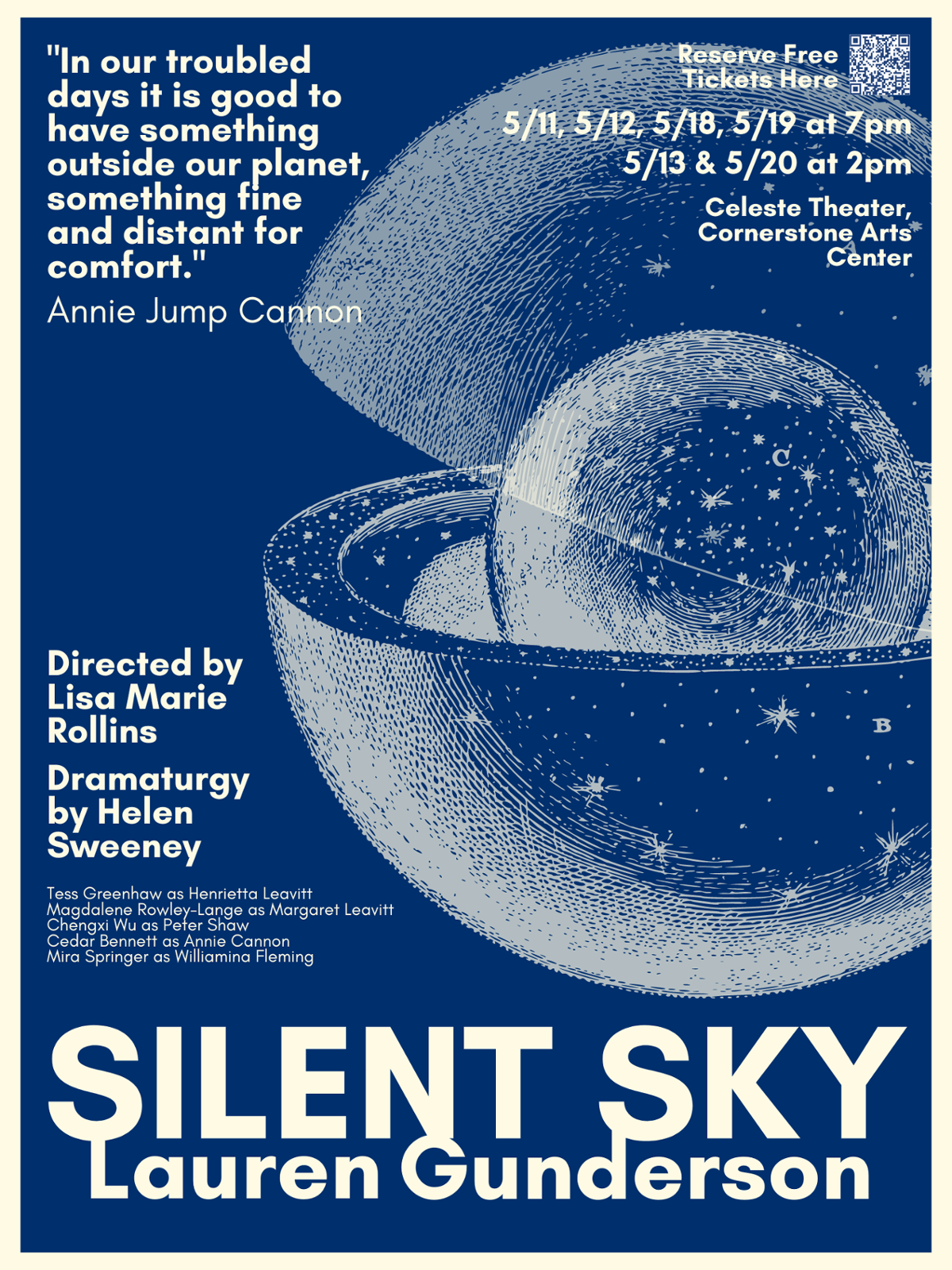

The Department of Theatre and Dance invites you to Opening night of SILENT SKY by Lauren Gunders

The Department of Theatre and Dance invites you to Opening night of SILENT SKY by Lauren Gunders

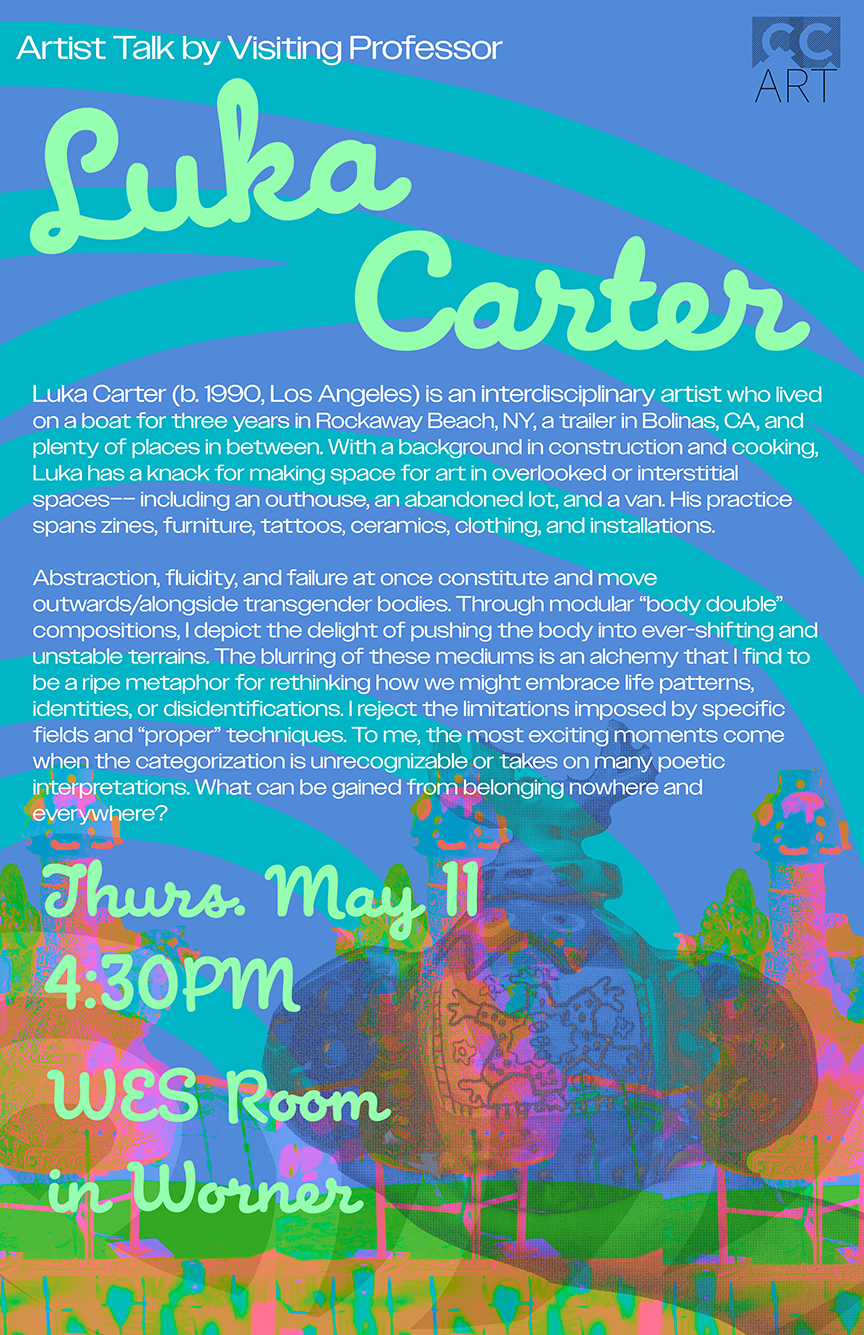

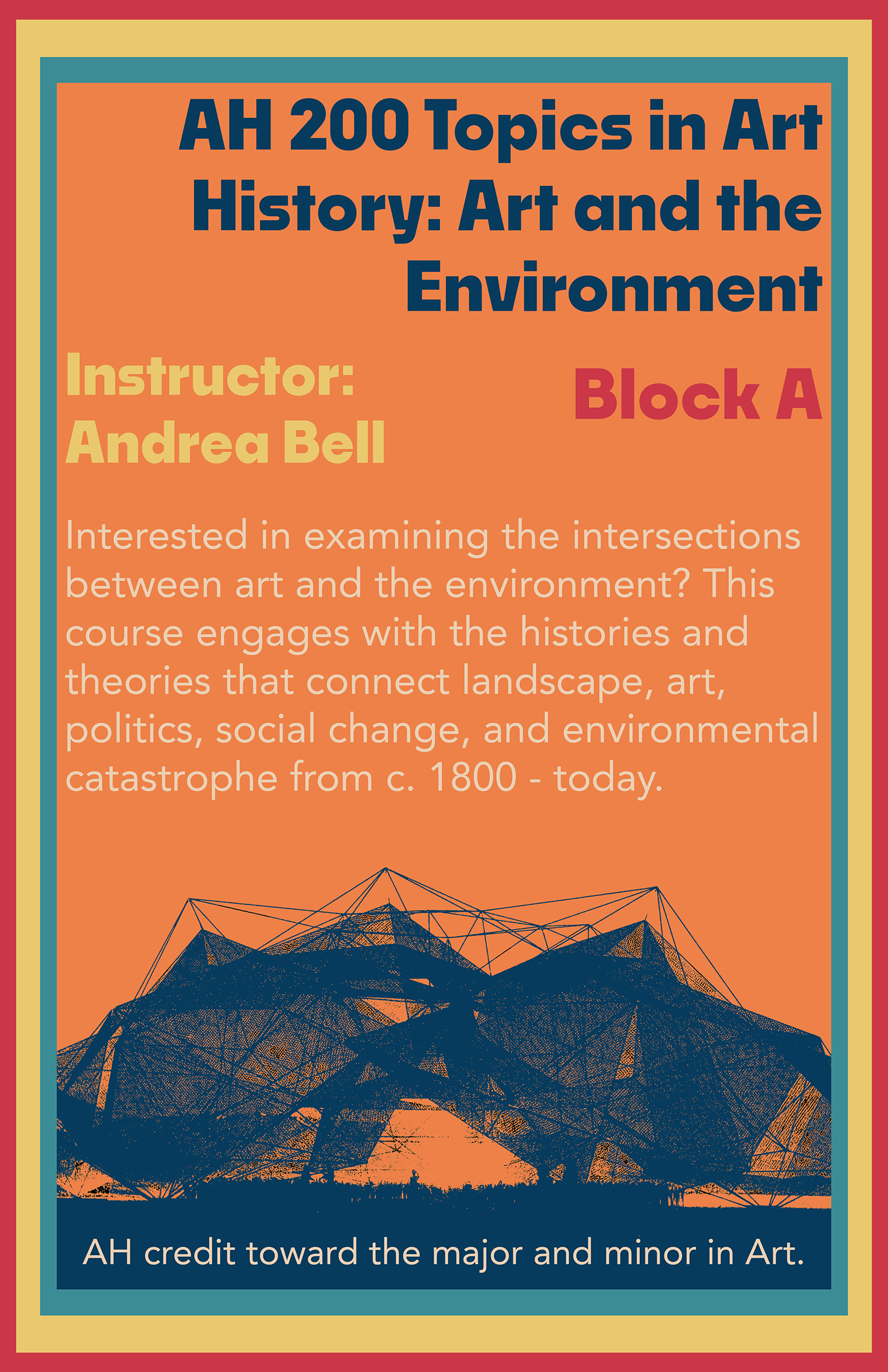

AH200 Topics in Art History: Art and the Environment Instructor: Andrea Bell

AH200 Topics in Art History: Art and the Environment Instructor: Andrea Bell