By Alana Aamodt ’18

Do you ever find yourself scrolling through Facebook endlessly or aimlessly lounging around, all while knowing you could be running, journaling, or doing another favored hobby?

Parker Schiffer ’15, found himself in this common pattern, opting for Netflix over climbing and skiing during his junior year at CC. He knew which activities would make him happy, so why wasn’t he doing them more? This questioning led to the idea for his senior psychology thesis, which eventually led to the recently published study, co-authored with Colorado College Professor of Psychology Tomi-Ann Roberts, titled “The Paradox of Happiness: Why are we not doing what we know makes us happy?” in the Journal of Positive Psychology.

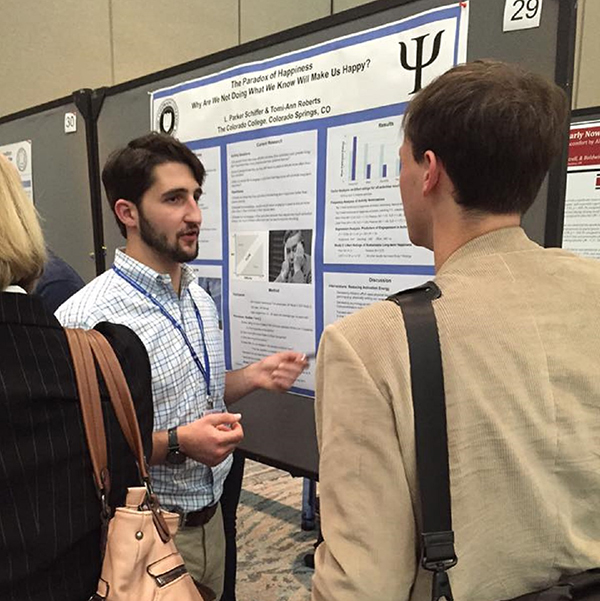

Their collaborative research already is garnering media attention, with a feature appearing in the British Psychology Society’s Research Digest. Schiffer also presented the research last January at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology convention in San Diego.

Schiffer and Roberts’ work expands on a concept from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology and management at Claremont Graduate University, of “flow,” a highly focused mental state, achieved through flow activities, which “require clear rules, challenge, a high investment of energy, and have been shown to promote long-term happiness better than low investment, passive activities,” according to Schiffer and Roberts’ research.

Roberts describes Csikszentmihalyi’s idea of happiness as “not something that happens to us, but rather comes to us when we invest our energy in activities that challenge us.” Their study seeks to determine if people realize which activities will lead to long-term happiness and to understand why many opt for passive activities rather than active, happiness-inducing ones.

Csikszentmihalyi, who was the commencement speaker and an honorary degree recipient in 2002, recently spoke at Colorado College for the Psychology Department’s Sabine Distinguished Lecture.

Three hundred people participated in two surveys to reveal that people already know which activities are conducive to lasting happiness, but the pull of anticipated enjoyment brought by leisurely activities often wins out. There is a daunting quality to the high-energy flow activities, Roberts and Schiffer discovered.

“Our study results made us realize that we do not need lists of what will make us happy popping up on our Facebook feed that we’re endlessly refreshing,” Roberts explains. “We know what will make us happy. We just need to find a way of overcoming a feeling that it’s too daunting to get our running gear on, or to put out our paintbrushes and easel.”

Methods to overcoming this feeling are central to Schiffer’s current work in graduate school at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California, where he studies positive developmental psychology under Jeanne Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi.

Schiffer describes one of his current projects: “I am currently working on a smartphone application-based intervention that seeks to help people overcome the hurdles of activation energy they face when trying to engage in flow style activities.”

As far as personal takeaways and how his life has changed since his junior year slump, Schiffer says he intentionally budgets time for activities like climbing and running during high momentum periods of the day, when he has plenty of energy. He sums it up, saying “there’s nothing worse than knowing what you should do, knowing why you’re not doing it, having an idea of how to help yourself, and still not engaging.”