Written after microwaving cold coffee. At that point in the week.

On Friday, Lily left the others to brave the metro by herself and attend an interactive simulation of the UN climate negotiations. The participants were divided into five groups representing the US, EU, China, India, and the LDCs (least developed countries). Each group was asked to come up with their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), which included the year they intended to cap emissions, the year they intended to reduce emissions, and how much they planned to accept from/contribute to the Green Fund. Like the real negotiations, the aim of the simulation was to come up with national targets that would limit the global temperature increase to 2 degrees C.

The assembly boos the simulation’s “President Obama” as he proposes the US’s weak intended commitment

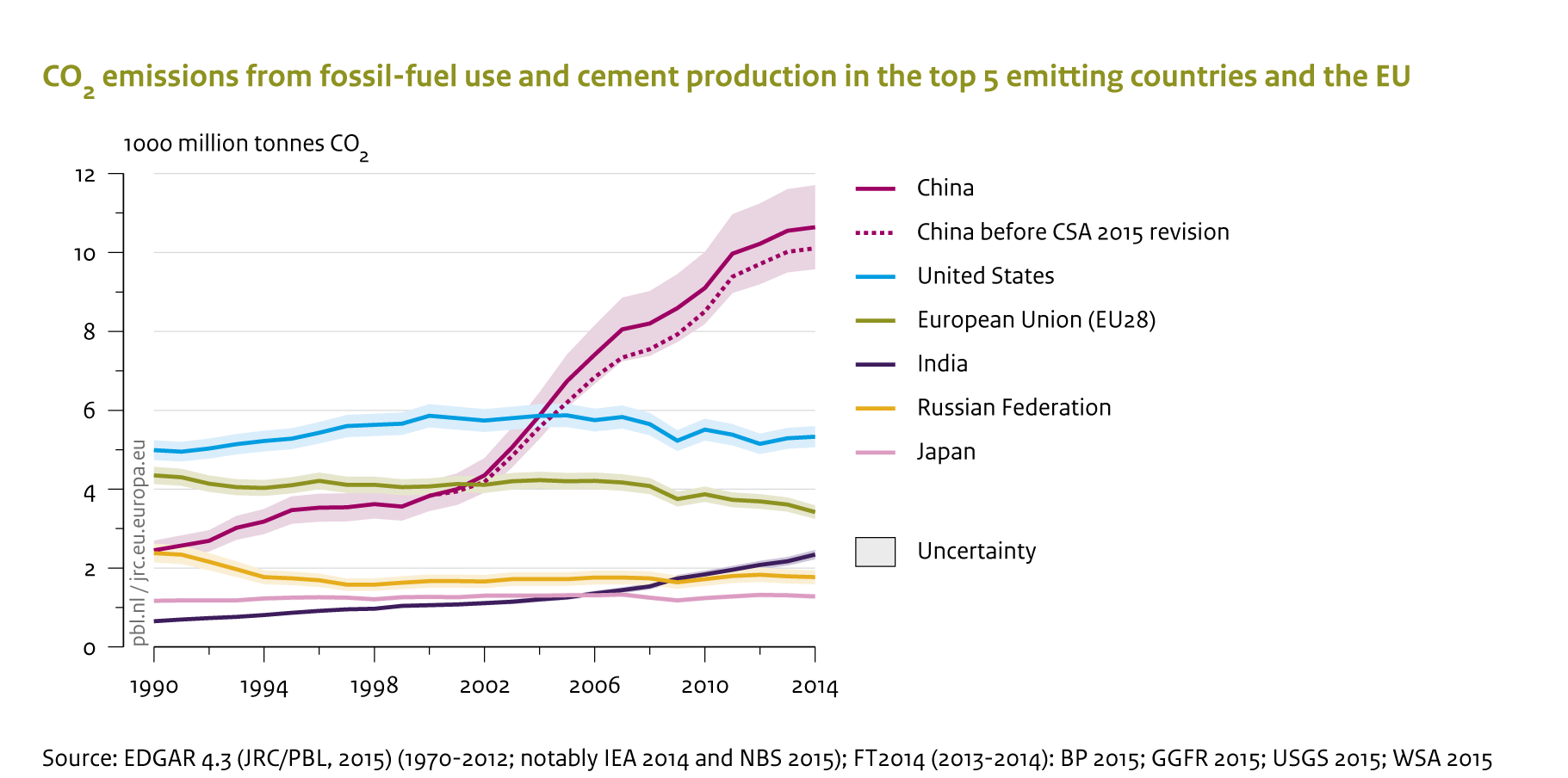

Lily’ country– India– had a particularly tough time coming up with an INDC and negotiating an agreement. While India is one of the world’s top polluters, it generates only a fifth of annual emissions of China and a third of annual emissions of the United States. Furthermore, while India has achieved significant national growth in recent years, it’s GDP per person ($1,688) remains relatively low, and the nation has prioritized poverty alleviation and economic development over emission reductions. For this reason, India (in both the simulation and the real-world negotiations) argues that countries with greater historical contributions to climate change and with fully developed economies should bear the burden of emission reductions.

This question of how the burden of climate change should be shared among developed and developing nations, and nations with differing historical contributions has dominated the COP21 discussion. Approximately three-quarters of the total CO2 released by the burning of fossil fuels since the start of the Industrial Revolution has come from developed nations. Emissions per person in the US, EU and other developed countries are far higher than emissions in the developing countries (i.e., India, and other developed countries). With less than 5% of the world’s population, the US alone generates 15% of global emissions.

Unfortunately, developing countries– particularly island nations– are expected to experience the greatest impacts from climate change and are the least able to adapt. In our simulation, we greatly exceeded the 2 degrees limit when we exempted developing and low-emitting nations from contributing to emission reductions. It became imperative for all countries– including India and other developing nations–to act. We saw that regardless of historic responsibility, all nations must cap and cut emissions growth by 2100. This is where the Green Fund plays an important role in negotiating a fair agreement and making global emission reductions possible. The Green Fund is a $100 billion annual fund promised by rich countries to help the developing world reduce emissions, adapt to climate change, and transition towards a low-carbon development model. UN negotiators continue to debate how much particular nations should contribute to and take from the fund. The outcome of these decisions could make or break the potential for a meaningful climate agreement and successful negotiation session at COP21.

That night, we hopped on over to the Louvre to snag free tickets into the museum (free admission on Friday nights!). We wanted to take a good look at Mona before we return to the gallery on Wednesday to protest for cultural divestment (stay tuned!).

Leave a Reply