I came to Martinique to learn more about the history and culture that produced the women I am studying, through my experiences of the land- and city- and seascapes as well as my reading. But how does one come to “know” anything about a society and geography that seems so far removed from one’s own?

I had lunch the other day with a young woman I shall call “Lucie.” I had never met her before, but she had a summer position in the office of someone I know in Colorado. When she heard that I was going to Martinique, she composed for me a very detailed “to do” and “to eat” list~ the kind of list that only someone who knows and loves a place can produce. Born in the Hexagon (mainland France), Lucie is the daughter of metropolitans who came to do their tours of duty in Martinique 22 years ago. Unlike the majority of metropolitan government workers who do their “outre-mer” duty to accumulate the bonus points and return to the mainland after 2 or three years, Lucie’s parents decided to form their careers in Martinique. Thus, Lucie was raised and received all of her education in Martinique, though she is now pursuing graduate studies in the United States. She was inspired to learn English through listening to American music, though she received all of her primary and secondary school education at the most exclusive school in Martinique.

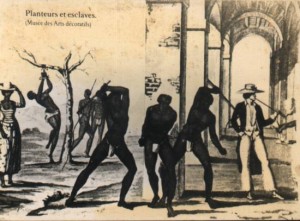

One of the first questions I had for Lucie was whether “békés” still exist, and if “béké” ~ a word I have usually heard spoken with contempt~ is a word still used to describe the descendents of planters who established their multi-generational wealth through the slave trade, sugar cane, and rum. Oh, yes, she told me. They still exist, are still called “békés,” and still control all of the wealth on the island. There are around 5000 of these families, but they are very insular. They own all of the grocery store chains, car dealerships, rum distilleries (all of them family businesses several hundreds of years old), and major real estate. They all go to Lucie’s school, even if it involves a 4-hour round-trip daily commute. They go to France or Miami for their university degrees, and return to run the family businesses. They only marry each other~ even to marry a French white person would be unthinkable. According to Lucie, they are deeply racist.

One of the first questions I had for Lucie was whether “békés” still exist, and if “béké” ~ a word I have usually heard spoken with contempt~ is a word still used to describe the descendents of planters who established their multi-generational wealth through the slave trade, sugar cane, and rum. Oh, yes, she told me. They still exist, are still called “békés,” and still control all of the wealth on the island. There are around 5000 of these families, but they are very insular. They own all of the grocery store chains, car dealerships, rum distilleries (all of them family businesses several hundreds of years old), and major real estate. They all go to Lucie’s school, even if it involves a 4-hour round-trip daily commute. They go to France or Miami for their university degrees, and return to run the family businesses. They only marry each other~ even to marry a French white person would be unthinkable. According to Lucie, they are deeply racist.

A couple of days later, I meet my first béké, in the parking lot of a friend’s apartment building. A few days after that, while waiting for my husband to arrive at the Aimé Césaire Airport, I see a family I am sure are békés. The man and woman, perhaps in their late sixties, have the faces of French aristocrats from 17th-century paintings, and they have the self-contained air of the wealthy. They, like me, are waiting for someone to arrive. As I watch them, I try to imagine they are something else: an haute-bourgeois French couple who has bought a retirement home in Martinique, and are waiting for their children and grandchildren to arrive for their annual visit from the Hexagon. A deposed prince and princess from a kingdom that no longer exists, in exile in Martinique. A retired French businessman and his wife. A petit blanc with a government post. But no, they must be békés, with that air of familiarity with the airport waiting room and stolid assurance. They don’t seem to register the presence of anyone else in the room.

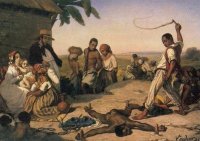

I have an unhealthy curiosity about the békés. What would it be like to know that your fortune and status, preserved throughout centuries, was built on the exploitation of suffering of enslaved human beings~ and not to care? To still have contempt for the descendants of those who made your fortune? To depend upon people for whom you have no respect to continue to build your wealth?

I have an unhealthy curiosity about the békés. What would it be like to know that your fortune and status, preserved throughout centuries, was built on the exploitation of suffering of enslaved human beings~ and not to care? To still have contempt for the descendants of those who made your fortune? To depend upon people for whom you have no respect to continue to build your wealth?

When I expressed shock to Lucie about the prices in the food stores, even for local produce, and speculated that it had something to do with an island economy, she laughed. “It’s because the békés own all the chain stores, and between them, they set the prices. It got so bad there was a strike against the grocery stores, but people can’t not use grocery stores, so the strike ended.” The taxi driver who brought me to the airport on Sunday told me that it would be cheaper for a Martinican who wants a French car to fly to France, buy it there, and ship it back, then to buy it at a Martinican dealership. Yet that’s not what Martinicans do.

I’m curious whom the cool, quietly but expensively dressed older couple is meeting. And soon I see: a young man, perhaps fourteen or fifteen, with golden curls and very expensive luggage. He, too, has that ease, that obliviousness, of the privileged. The elderly couple~ they must be grandparents, are happy and relieved to see him, but the embraces are perfunctory. I half-expect a valet to materialize to collect the young man’s Louis Vuitton matched set. The three wait by the exit for something or someone, but there’s my José! I forget those people, who because their descendents lived in Martinique and not Guadeloupe, didn’t lose their heads in the French Revolution, when one of the revolutionaries sailed to Martinique with a portable guillotine to do the revolution’s work “outré-mer.”

One Response to Békés