Imagine what it would be like to unknowingly ignore half of your world. Your vision is intact, but you have a severe a lack of attention directed towards an entire half of what you experience, almost as if you don’t actually see it, but you CAN. You can sense it, you just don’t attend to it. This is what patients with unilateral neglect, a type of attentional disorder, experience. It can occur after damage (a stroke, traumatic injury) to the brain, often to a region called the right inferior parietal lobe.

Imagine that you can speak with excellent fluency regarding intonation and speed, but it’s all gibberish. People try and tell you that you’re not making sense, and although you can hear others’ speech, you are unable to comprehend what they’re saying. They try to tell you that you’re not saying anything meaningful, but you’re unaware because you can’t understand them. This is what it’d be like to live with Wernicke’s aphasia, a speech disorder that can occur after damage to a region in the left temporal lobe. To see and hear how a patient with Wernicke’s aphasia may act and speak, I recommend this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVhYN7NTIKU.

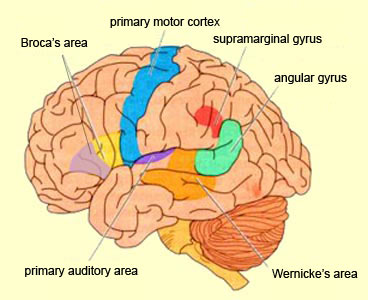

Imagine that your arms and hands function perfectly fine and you’re able to move them, but if somebody verbally asks you to act like you’re brushing your teeth, you can’t. You know how to brush your teeth, and you know what it looks like, but you cannot physically bring your hand up to your mouth and brush an imaginary toothbrush back and forth when VERBALLY asked to do so. But, if somebody shows you what this movement would look like, you could mimic it just fine. This is what patients with a disorder called dissociation apraxia experience. They have trouble taking a verbal command and turning it into a complex movement. This deficit results from damage to the pathway in the brain connecting Wernicke’s area (the comprehension area of the brain) to an area of the brain where the “instructions” on how to perform a movement are stored (a.k.a motor engrams in the left angular and supra marginal gyri for anybody who wants that level of detail).

Imagine, now, that you can spell words with great proficiency, but you can’t physically write them. You can write numbers, but not letters. You can even explain what letters look like in enough detail to others that they know what letter you’re talking about. But nevertheless, you can’t write the letters down. You can write the digit “0” (zero), but not the letter “O” (oh). Somebody with agraphia, an impairment in writing capability, may have these experiences. This may occur due to damage in the left hemisphere of the brain as well. [Student presenters discussed this specific case study in class: “When writing 0 (zero) is easier than writing O (o): a neuropsychological case study of agraphia” by Delzer, Lochy, Jenner, Domahs & Benke, 2002].

The disorders I briefly described above are just a handful of the countless disorders we learned about during week 2 of Human Neuropsychology. They are all so fascinating, and often resulted in mini-existential crises during our class discussions. Despite how cool and exciting these disorders are to learn about, if you think about what it would be like to actually have or know somebody with any these disorders it’s quite mind-numbing. Something I really appreciate about this class is that we learn about more than just the disorders themselves. We learn about how these disorders affect real people. One of our texts for class, Michael Mason’s “Head Cases: Stories of Brain Injury and Its Aftermath”, provides personal accounts and experiences regarding traumatic brain injuries. Rather than an anatomy and science heavy text, it’s the human and emotional side of brain injuries, a perspective that’s equally important when learning about the brain.

We’ve also had the chance to personally meet and speak with an individual who sustained a traumatic brain injury. She came to class and told us her story, starting with a car accident, leading to a coma, and subsequently months of rehabilitation. Despite everything she had gone through she was unbelievably positive, which was an extraordinary thing to see and hear.

We also talk a lot about neuro-rehabilitation in general in this class, something that can often be overlooked when it comes to many neuropsychological disorders but is of utmost importance. Sometimes rehabilitation can help with these disorders, but other times our current resources may not be sufficient. But realizing the impact of neuro-rehabilitation, when it’s available, is crucial.

Tomorrow, we will be visiting Craig Hospital in Denver, CO (http://craighospital.org). I am really looking forward to it! Thursday we will be heading back up to Denver to attend the International Neuropsychological Society’s 43rd annual meeting. Then, I’ll be lecturing on Friday about emotional disorders. It’s a packed week…but, that’s the block plan! I love it.