Today marks the beginning of an adventure for me, and like all true adventures, it is equally exhilarating and terrifying. Though I am a senior, and feel like I’m starting to get the hang of psych classes, this one is a little intimidating. I signed up for “Gazing” because I think Tomi-Ann is a really bright woman, and was happy to take any class she was excited about. But in truth, I know very little about the actual subject matter of the class. In my defense, it’s a big mix of things: emotion, art history, and gender studies. I know a little about emotion, although I haven’t taken that psych class yet (stay tuned for 5th block), but I know almost nothing about gender studies or art. A lot of this will be new to me, but I’m going to do my best to convey what I’ve learned.

Today marks the beginning of an adventure for me, and like all true adventures, it is equally exhilarating and terrifying. Though I am a senior, and feel like I’m starting to get the hang of psych classes, this one is a little intimidating. I signed up for “Gazing” because I think Tomi-Ann is a really bright woman, and was happy to take any class she was excited about. But in truth, I know very little about the actual subject matter of the class. In my defense, it’s a big mix of things: emotion, art history, and gender studies. I know a little about emotion, although I haven’t taken that psych class yet (stay tuned for 5th block), but I know almost nothing about gender studies or art. A lot of this will be new to me, but I’m going to do my best to convey what I’ve learned.

Today was our first day of class, and I’m already in awe. We visited Michelangelo’s statue of David, which you have probably seen if you have ever looked at any art before. I had seen David many times; from the cover of my textbook to funny cooking aprons- David is all over the place. But I have to say that seeing him in person felt very different. It was almost like meeting a celebrity. Larger than life, and beneath a bright skylight, David truly commands attention.

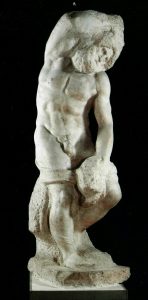

The statue itself is at the end of a long corridor, lined with other Michelangelo statues, called The Captives. These tortured-looking figures emerge from the stone, their incomplete figures seeming tethered back. Rock melts from their extremities and crushes down on their heads, forcing the statues into strained and contorted poses. There is some debate as to whether the statues are intentionally unfinished or not. Michelangelo used to say that in carving statues, he was simply carving out figures that existed independently in the stone, freeing them. It is possible that The Captives are meant to depict the process of the statues escaping.

The Captives. These tortured-looking figures emerge from the stone, their incomplete figures seeming tethered back. Rock melts from their extremities and crushes down on their heads, forcing the statues into strained and contorted poses. There is some debate as to whether the statues are intentionally unfinished or not. Michelangelo used to say that in carving statues, he was simply carving out figures that existed independently in the stone, freeing them. It is possible that The Captives are meant to depict the process of the statues escaping.

In sharp contrast to The Captives, David is very much complete. Every detail of his body is carefully etched out, from the curls in his hair to the veins beneath his skin. From afar, David looks very relaxed, leaning casually to the right, and gazing over his left shoulder with calm self-assuredness. We guessed that the statue represents David just after he slew Goliath.

Yet up close, the statue adopts a new meaning. David’s expression is strained, his brow furrowed. All of David’s muscles are tensed, as he rocks nervously between feet. His soft gaze seems suddenly intense and pensive, as though he is planning a way to beat the giant. Though the statue is physically colossal, David looks small and afraid.

Seeing The David led us to a discussion about what is so special about seeing the “real David” as opposed to pictures on the internet, or even a life-sized replica. In the same way seeing a rainbow or the totality of an eclipse inspires, seeing art in it’s natural place in a museum inspires the viewer to connect with a miracle. We might picture Michelangelo possessed by inspiration as he chipped away at the marble, really feeling the sweat collect on his brow and his arms become weak with the effort. We might wonder what story Michelangelo wanted to convey, and why he chose to depict David as he did. In a museum setting, the statue looks so grand, and demands the attention it deserves. Yet in museums, art can easily become mystified by scholars, over-explained by experts so that “common people” (like me) cannot have a chance to interpret the work on their own. Gazing upon The David outside of a museum (looking at a photo of the statue or replica), begs the viewer to connect with the piece of artwork instead of the artist. Because viewers outside of the museum are given less historical information about the piece, they have to make their own stories to explain the work. Both contexts are valuable, but for totally separate reasons. The style of seeing is shaped by the context. I am struck by the visceral feelings it inspires and the impacts it leaves.