Where did the potato on your plate come from?

We departed from Baca Campus Monday morning on a quest to learn more about America’s industrial farming industries, specifically large-scale potato farms in the San Luis Valley. I was not particularly excited to get up at 7:00 am to see something as mundane as potatoes. Aren’t they just potatoes, what could be so interesting about them?

Jamilah M., with her constant optimism, said “Nghi, we’re going to see the most potatoes we have ever seen in one day today” in an effort to make the trip more exciting. Oh boy, she was right. We saw potatoes alright.

We met up with Heather Dutton, manager of San Luis Valley Water Conservancy District and fifth-generation San Luis Valley resident. She brought us to Spud Grower Farms to check out their potato harvest. At first the field looked empty and I thought “Where are the potatoes? That’s all I came here for.”

Our first view of the potato circle

It somehow never clicked in my brain that potatoes are root crops, and root crops are underground. As we walked through the field, I saw small potatoes left behind on the ground. Can you spot what’s potato and what’s rocks?

The potato vines in the picture are dead because they are “beaten to death” 3-4 weeks before harvesting so the potato skin can have time to harden and dry out. If potatoes are harvested right away, the skin could easily peel off and get bruised.

While we were standing there, harvesters came by and scooped up the potatoes from the dirt, passed it through a conveyor belt to shake off anything that’s not potatoes and left them on the ground for the next round of harvester trucks to come pick them up. Sometimes the harvesters will miss some potatoes, and while unfortunate, it’s not worth it to go back over a row twice.

We were standing on a quarter section aka a crop circle. Each crop circle yields around 5-8 million pounds of potatoes every season. Spud Grower Farms grows 13 circles of potatoes annually, and another 13 circles of quinoa and barley. However, they predominantly focus on potatoes because it’s their cash crop. Farm Manager, Michael Curtis, is 1 of 4 full-time farmers working on the 26 crop circles which makes up the farm. To put this into perspective: there are only 4 farmers working year-round to make sure 81 million (2018 yield) pounds of potatoes gets into big grocery stores like Costco, Sam’s Club, Krogers.

Pictured is Heather (left) and Michael (right).

(DID YOU CATCH THAT? 81 MILLION POUNDS! And that’s barely 1% of annual American potato demand).

We, as consumers, demands perfect potatoes. Potatoes coming from the San Luis Valley could be repackaged into the potato buyer’s packaging. This process strips the San Luis Valley identity from the potatoes, thus making the origin of the potatoes untraceable.

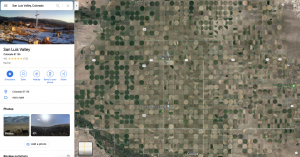

Crop circles in the San Luis Valley. Credit: Google Maps: Satellite.

Even though Spud Grower Farms grow a massive amount of potatoes and use industrial machinery, they are first and foremost a family farm. They care about their potatoes, try to minimize pesticide usage by fighting diseases with cover crops, and replenish the soil as much as they can.

Industrial American farming gets a bad rep, but as Heather puts it, “It’s not about the size of the farm, it’s about the ethics.” Michael added, “We would never grow something that we wouldn’t eat ourselves. I don’t buy potatoes from the store, I come out to the field and get potatoes to feed my own kids”

Heather and Michael also touched on water issues in Colorado. “80% of the population in Colorado is on the front range, yet 80% of the water is on the western slope. This puts a stress on municipalities to provide water for their constituents.”

Investors from Denver are looking to come into San Luis Valley, buy land from farmers to acquire the land’s water rights and groundwater wells, and pipeline the water to urban areas. This leaves farms like Spud Grower Farms left to worry about the future of water and the make-up of the farming community. Even though San Luis Valley sits on a large water aquifer, it’s disappearing more quickly than can be recharged.

While our urban lives are seemingly disconnected from farmers in the San Luis Valley, are we truly disconnected? The type of house we buy, the lawns we choose to water, the food we choose to eat, it’s all affecting the water reservoirs in Colorado and farmers around the state. If farmers like Michael were to stop growing food, where else would our food come from?

Bonus pictures of the potato sorting facility:

The beautiful Meghna Bagchi ft. 500,000 lbs of potatoes in the back.