A reflection on the failures of climate finance negotiations at COP29 from a first-time attendee.

By Ella Reese-Clauson ’26, International Political Economy

Joyce Banda, former president of Malawi, hurried into Side Event room 7 at the Twenty Ninth Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Climate Change Conference surrounded by a group of her advisers and coworkers. Still bundled in a long down jacket and toting her carry-on suitcase, Banda and her cohort had come straight to the COP29 venue from Baku’s Heydar Aliyev International Airport. This particular event was titled “From Commitments to Action: Mobilizing Climate Finance for Effective Implementation” and boasted an impressive panel of experts including Banda, Honorable Minister Sithembiso Nyoni of Zimbabwe, former Director General of European Investment Bank Global Andrew McDowell, and United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) executive director Jorge Moreira da Silva.

Banda collapsed into her seat and launched into a tired rant of her qualms with the UNFCCC. It has been over thirty years, she detailed, since the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) that formed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and laid the groundwork for COP. In those thirty two years, Banda and her compatriots had heard about pledges that were never realized. Year in and year out, she had “stood by helplessly” as she watched her constituents suffer because of these unmet promises. She watched as entire villages were wiped away and she listened as those who lost their homes, families, and livelihoods concluded that God was cursing them for their own behaviors, unaware that they and the rest of the Global South were paying the price for “sins [they] did not commit—” the sins, in the form of emissions, of the Global North. She wondered aloud whether she would come to COP again and whether it was a waste of time and resources for a country like Malawi to send such essential members of their governing body away for two weeks every year for nothing to be accomplished. “It’s been a year,” she noted “and [they] are back here suffering.”

The finance that was successfully gathered, Banda explained, took a year to access, by which point three more disasters could strike. But on the local level, change was happening. The private sector was successfully funding projects within Malawi and the country had received the highest project price for any climate mitigation investment project in all of Africa the prior year. So, she mused, “It’s happening at the small scale. Why is it not happening here?” Her conclusion reverberated through the room as the discussion moderator organized his notes: “We know exactly what to do in this room, but it’s not happening.”

A student ethnographer, I had entered COP29 with cautious optimism. I had left the United States the day after the harrowing 2024 presidential election in which Donald Trump was reelected, a result that solidified the nation’s path of pulling out of the Paris climate accord. The morning of the election, I was grasping for hope and placed it squarely on the shoulders of the UNFCCC and COP29, a perhaps naïve decision. Banda’s remarks toppled that hope.

But on the first Tuesday of the conference, my first day badged for the conference’s restricted-access Blue Zone, I had felt a surge in hope. I felt a childish sense of pride as I donned my UNFCCC observer badge for the first time, my badging organization—Earth Law Center—and full name printed beneath my picture in gleaming silver font. The first session I attended was organized by the faith pavilion, “Beyond Numbers: An Interfaith Dialogue on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) from Faith and Ethical Perspectives.” The event was held in Special Events Room Hirkan, a large room near the entrance to the Blue Zone with tables arranged in a rectangle around a series of televisions projecting the images of panelists. Rows of chairs stood between the entrance and the roundtable, presumably for the audience. I took a seat in one of these chairs, pulling out my field notebook and checking my schedule for the day. As the discussion began, however, the moderator invited the audience to join the roundtable, hoping to create a non-hierarchical conversation rather than a traditional panel. I relocated behind a tabletop microphone that, though I never turned on, gave me a swelling of faith in the COP29 process and its accessibility.

Faith leaders from more than a dozen distinct religions globally sat around the table with me, vehemently critiquing existing processes. They spoke of the need for climate finance to take the form of grants rather than loans to prevent cycles of debilitating debt, the need for this finance to go to Indigenous communities with local knowledge, and the need for continued energy towards adaptation and loss and damage funds. Though the message did not reflect well on the historical COP process, the fact that these conversations were taking place within the hastily constructed temporary hallways of COP29 gave me hope.

This paper will attempt to detail the path of that hope at COP29, starting first with some of the more encouraging sessions I went to before digging into the fissures that made that faith vanish. I will bring the reader with me as I witness firsthand some of the conference’s many failures but also highlight a few successes that leave me feeling a sense of faith, no longer in the UNFCCC and its institutions but in the people that make COPs run.

Banda’s remarks on global climate finance ring true for many developing nations globally. But first, some context on climate finance: The original 1992 Convention on Climate Change, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, and the 2015 Paris Agreement all “call for financial assistance from Parties with more financial resources to those that are less endowed and more vulnerable” (UNFCCC). That call has had varying degrees of legal ‘teeth’ for accountability, but, starting with the Copenhagen agreement in 2009, 43 ‘developed’ countries were expected to collectively provide $100 billion USD annually to 153 ‘developing’ nations (UK Parliament 2024). This money was then divided into two categories: mitigation—“actions to prevent or reduce greenhouse gas emissions”—and adaptation—“actions required to manage the impacts of unavoidable climate change” (UK Parliament 2024).

Despite this commitment, that $100 billion annual quantum took until 2022 to be fully realized, leaving communities reeling in the meantime (OECD). The money comprises a combination of bilateral (between two countries) public funds, multilateral (between more than two countries) public funds, export credits, and mobilized private funds in a mixture known as ‘blended finance’ and largely is in the format of loans for specific projects, such as a wind farm or a dam that could generate returns for investors. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, much of this money never reached the communities that needed it. The money was inaccessible, often taking a year or more to access when communities needed it urgently. The process of requesting these funds is also bureaucratic, leaving many in-need groups unaware of how to apply. The money that did get sent out often got stuck with intermediaries or corrupted governments and didn’t reach the areas in need.

In Paris in 2015, nations formally recognized the need to address loss and damage from climate change impacts, particularly for developing countries. This acknowledgment was strengthened at COP26 in Glasgow with the creation of the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage, but the crucial question of funding remained unresolved. Finally, at 2023’s COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, nations achieved a historic breakthrough with the operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund. The fund was launched with initial pledges totaling $792 million, with the largest contributions coming from the UAE ($100 million) and Germany ($100 million). However, these pledges fell far short of the estimated annual loss and damage needs of developing countries, which range from $290-580 billion by 2030.

In that first week, I attended session after session where panels composed of representatives of Multilateral Development Banks (MBDs), environmental ministers of various small developing countries, activists, and NGO employees proposed innovative, clearly delineated ideas to support climate finance. Over and over, I sat in crowds largely made up of observing delegates, furiously scribbling notes as panelists presented the problems and proposed solutions. They spoke tiredly of risk and questionable good governance warding off private sector investment and lamented nonquantifiable lifestyle losses and damages before launching into animated proposals for innovative new ideas like Climate and Disaster Risk Finance and Insurance (CDRFI), expedited corruption assessments to get money on the ground quicker, decentralized allocations of climate finance to prioritize local solutions and indigenous knowledge, cash transfers through mobile banks, and more. I tuned in to roundtables where ministers from high-risk countries outlined their nations’ most dire climate troubles and the exact finance and support they needed.

The problems were grave but I felt a sense of encouragement hearing so much consensus from people who seemed, in my mind, to have the power to make the change.

Slowly, however, my faith began to deteriorate. On day six of the conference, I made it into the room for a high-level dialogue with nongovernmental organization (NGO) constituencies called “Mobilizing Adequate and Urgent Climate Finance.” The talk, despite being a mandated dialogue, was filled with empty chairs. COP29 president, Mukhtar Babayev, and UNFCCC Executive Secretary, Simon Stiell, opened up the conversation with a practiced spiel on the need for these talks, noting that NGO groups are “closer to the needs of the people on the ground.” After their own speeches, the pair hurried out of the room escorted by teams of advisors. Whether or not they were headed to other meetings, the message was the same: they cared about the meeting enough to give a speech using the right words, but not enough to stay and listen.

The floor opened to the constituency groups and each one provided a brief intervention on their group’s needs. Liane Schaletek, representing the Women and Gender Constituency (WGC), gave what I found to be the most compelling presentation. With a PowerPoint full of intuitive graphs backing up her words, Schaletek outlined the problems with the existing climate finance framework—including the often-raised fact that the UNFCCC still lacks an exact definition for the term—and outlined a four-action-step proposal for raising public revenues through tax justice, a clear plan to reduce the cost of capital, and proposed reform for credit rating agencies. The presentation was the most defined action plan I had heard so far at the COP, yet so few representatives of member states were in the room to hear it and those that were were largely low-level trainee negotiators.

A representative of Chile perfectly encapsulated my thoughts, boldly turning on his microphone to challenge the existing UNFCCC structure. He explained that the UNFCCC packs schedules so full that negotiators lack the time to speak with constituencies. He emphasized the importance of this event and his disappointment in its sparse attendance. He wondered aloud whether it was time to look critically at the COP schedule to prioritize more events of this format.

Negotiators at COPs, I later found out, often stay in the venue into the early hours of the morning for days on end. Myra Jackson, UN Permanent representative in New York, Diplomat of the Biosphere, and rights of nature advocate, joined our delegation at COP29 and spoke once to the burden of the negotiator. According to her, negotiators often have to deliberately ignore anything—any need, any suffering—beyond the scope of what their country will allow them to negotiate “because it hurts” to keep hearing of the suffering and be unable to fix it.

These challenges with timing at COP were clear in many of the events I attended on the ground at COP29, where negotiators were noticeably absent and where civil society—non-state actors such as businesses, researchers, city officials or environmental NGOs—panelists talked in circles amongst themselves. The COP was seemingly split into two separate conferences, one deeper into the venue where negotiators and those with access—noticeably, this often included some of the many fossil fuel lobbyists present—would meet either multilaterally or bilaterally to come to the decisions that would come out of the COP, and one in the side event rooms, exhibits, and pavilion space where civil society engaged in climate actions, debates, and panels. Though negotiators had to walk through the civil society space to reach the plenary and meeting rooms where their work took place and though we as members of civil society were on occasion able to sit and observe high-level meetings, there appeared to be little interaction between the two.

This division is problematic because those making the decisions do not hear from those on the frontlines of the crisis. Nayoka Martinez Bäckström, First Secretary at the Embassy of Sweden, Dhaka, Bangladesh named the problem in a side event I attended called “Climate Change-Induced Displacement and Migration in Bangladesh,” saying that “those holding the pen” don’t know what is happening or who to talk to. In that room, we were “all likeminded,” convincing each other of things we already believed rather than speaking to those with the power to finance solutions. That talk, like many others I had observed, ended with clear policy prescriptions for what was needed to solve the problems they had addressed, but there was nobody in the room to hear them.

Joyce Banda had lost all faith in the UN and similar institutions, and she was not alone. COP29 was nicknamed the “Finance COP,” with its main goal being to agree upon the New Collective Quantified Goals, or NCQGs, to replace the previous $100 billion USD annual number. The goal was to provide a global finance target to support developing countries in their climate finance needs, aiding them in paying for the damages that wealthier, high-emitting countries caused. The stakes were particularly high given that the previous $100 billion commitment had taken until 2022 to be fulfilled—a full two years after its target date.

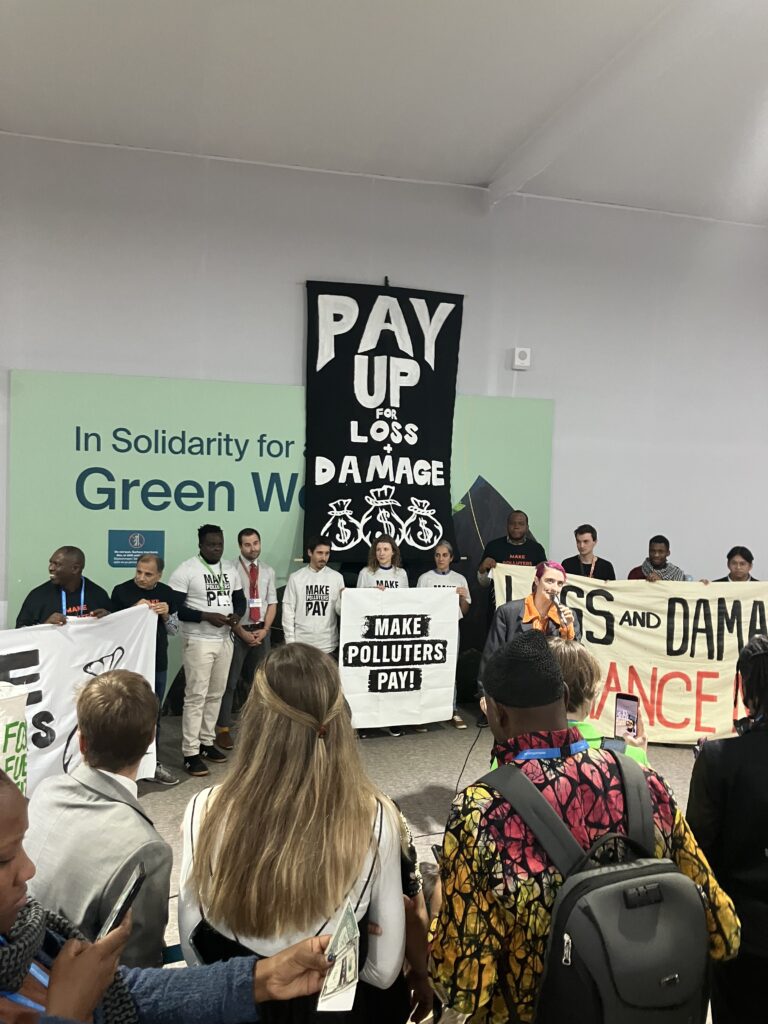

Throughout the first week, delegates largely from civil society had participated in actions chanting “climate finance in the trillions not billions” and wearing lanyards reading, “$5 trillion,” a message referring to the estimated debt owed to developing countries by high emitting nations. The figure wasn’t arbitrary—a report released by the Standing Committee on Finance in 2022 had estimated that developing countries would need $5.8-5.9 trillion for pre-2030 climate action to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. All of the tens of thousands of people attending the COP seemed to be holding their breath waiting for a number to come out.

Late in the second week, the NCQG initial draft came out. The text lacked a quantum—a specific number for how much annual climate finance they would agree upon—and was filled with brackets, a symbol the UNFCCC uses to denote something that is still under negotiation and has yet to be agreed upon. The bracketed sections revealed deep divisions: developing nations advocated for a baseline of at least $1.3 trillion annually by 2030, while developed nations pushed for much lower figures.

When the final draft was published days after the COP was supposed to have ended, the number was strikingly low: $300 billion USD. The global estimated need had been $1.3 trillion USD, a figure that is still conservative to many activists and leaders from the global South (Rokke 2024). More troubling still was how this number would be counted—the text included provisions that would allow private finance, loans, and existing development assistance to be counted toward the goal, rather than requiring new and additional public finance as developing countries had demanded.

The consequences of this result cannot be understated. For communities at the frontlines of the climate crisis, this deal will contribute to widespread losses of life and livelihood. It is, as Filipina development worker Tetet Nera-Lauron stated in a LinkedIn post after the fact, a “death sentence… co-written by the #fossilfuel industry, developed countries, the UNFCCC secretariat and the #COP29Azerbaijan presidency.” In response to the lack of consensus and the clear favoring of bilateralism, she stated that it “bulldozed whatever semblance of a process there is.”

Nera-Lauron is not alone in her anger. In every COP group chat I found myself in, members cried out against both the quantum and the process. Tweets, emails, LinkedIn notifications, and texts proclaimed different versions of the same message: people felt betrayed, angry, and scared. The “farce,” as Nera-Lauron called it in an action outside meeting rooms on the Sunday after COP, amounted to nothing more than crumbs.

The anger stemmed not just from the insufficient number, but from how it was reached. Throughout the negotiations, developed countries had engaged in what many observers called “forum shopping”—bypassing the formal multilateral process in favor of bilateral deals and informal consultations. This approach effectively sidelined many of the most vulnerable nations from key decisions about their own futures.

Myra Jackson, our delegation’s resident expert on all things UN who attended her 19th COP this year in Baku, stated plainly that “We’ve been played.” The process in Baku relied heavily on bilateralism that circumvented the prescribed multilateralism and consensus on which the UNFCCC relies. This shift away from consensus-based decision-making represented, for many, a dangerous precedent that could further erode the influence of smaller nations in climate negotiations.

The implications were particularly stark for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), who had come to COP29 with clear demands for scaled-up, grant-based public finance. Instead, they left with a commitment that not only fell far short of needed amounts but also failed to address their concerns about over-reliance on private finance and loans that could exacerbate already problematic debt burdens.

As we packed ourselves into the fabricated venue each day, the negotiators deciding between two insufficient quanta of 250 or 300 billion USD, the climate crisis did not pause. As Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, the Chadian indigenous peoples’ leader at the interfaith dialogue I attended, said, “Disasters are happening. Right now people are dying.” In Chad, “people are underwater”: Over 200 million people are homeless and thousands are dead from flooding. In the Philippines—the country ranked highest five years running for climate risk—an unprecedented four tropical cyclones made landfall within just 30 days in the month of the conference, affecting over 13 million people. In Panama and Cuba, hundreds of thousands were evacuated when Hurricane Rafael made landfall. The urgency of the climate crisis and the need for these funds are only increasing.

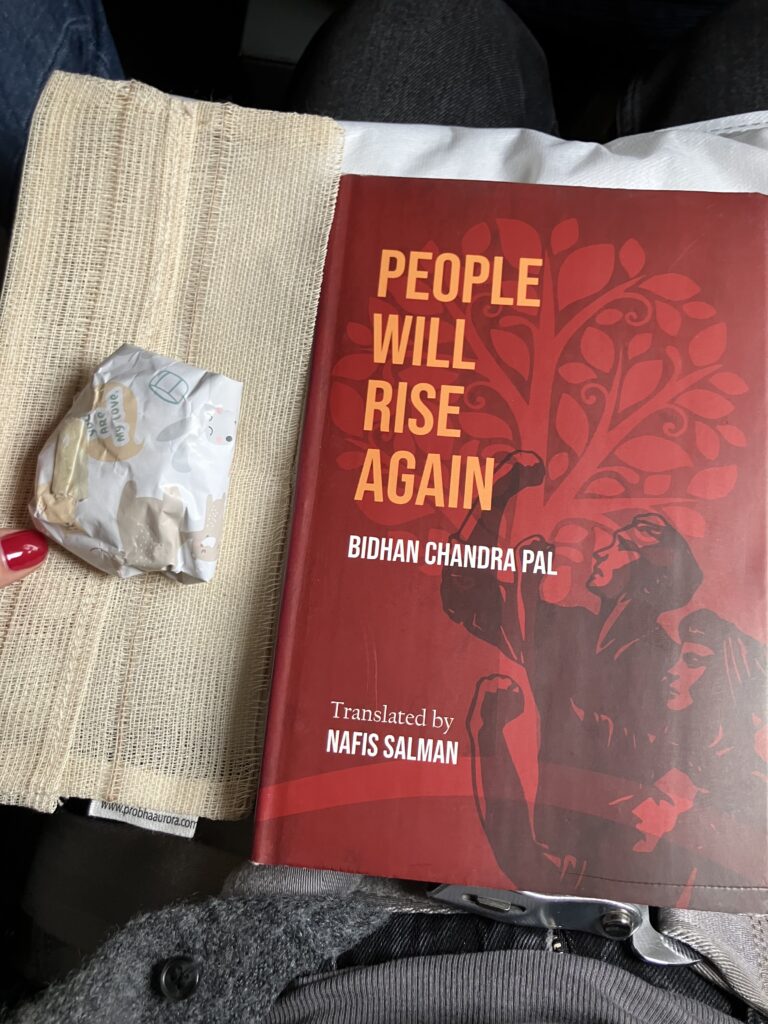

I entered the Baku airport on Saturday after COP feeling defeated. I stood in the line to check my bag with headphones in, downing the water in my new COP29 water bottle in anticipation of the security line. In the line for a flight to Bahrain, my blond-haired self stood out enough that the man behind me asked if I had attended COP. Clearly having arrived straight from the venue, the man, who introduced himself as Bidhan Chandra Pal, was still dressed in a suit jacket and tie. The Bangladeshi activist founded Probha Aurora, a youth-focused climate advocacy and green education group. On the side, he also acted as the national operator for the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE)-Bangladesh.

As the line inched forward, we discussed the COP. Chandra Pal was appalled to hear how dismayed I felt by the results. Hope gleaming in his eyes, he told me how encouraged he felt by this year’s conference. The smile never left his face as he spoke of the heavy youth engagement, the connections made, the increased emphasis on greening education and health, and the presidency’s robust youth volunteer program. He, unlike many people I had spoken with that week, was impressed by Azerbaijan’s sustainability commitments and believed that they would fulfill them. He urged me not to get bogged down in grief or frustration; to him, it was essential that youth in particular feel hope about the climate.

Bangladesh, Chandra Pal’s home country, is a member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) and, as its membership suggests, faces “severe and increasing climate risks” (World Bank 2022). The 2023 World Risk Index ranked Bangladesh ninth for climate risk, owing largely to rising sea levels and increasingly frequent and severe cyclones. It is estimated that, by 2050, Bangladesh will lose 17% of its territory to rising sea levels that threaten coastal and river-side regions and 13 million people are projected to become internal climate migrants (Veer 2025).

Bangladesh has been a leader globally for its local-level adaptation and disaster risk management work, taking drastic measures to successfully reduce cyclone-related deaths “100-fold” (World Bank 2022). But this work done within the country—a country that contributes only 0.4 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—does not make up for the insufficient action being taken by the highest emitting countries (World Bank 2022). Despite the best efforts of local NGOs and governments, floods, cyclones, and coastal erosion continue to displace communities.

The resulting internal migration presents several problems. The sparsely populated “Climate Change-Induced Displacement and Migration in Bangladesh” side event I attended addressed some of the non-economic challenges facing Bangladesh. Beyond the obvious economic consequences of losing one’s home and relocating to an over-concentrated and underresourced urban settlement, the panelists detailed, non-economic losses and damages abound. Forced out of their fishing livelihoods, many are forced to find new jobs despite a scarcity of openings and a lack of training. These communities, populations burgeoning with each new disaster, are generally deemed unsafe particularly for women and children: They often boast a lack of safe water, poor sanitary conditions, general poor health and frequent illness, rising sexual harassment, and absent social safety nets. The homes in these informal settlements are heat chambers, lacking ventilation and light, and are often rented under the table, prompting fears of eviction. Many regions are also seeing an increase in child marriage. Families, having been forced to move as many as four times in as many years, often see child marriage as a method of “risk transfer”: rather than having to tote around another mouth to feed, parents can marry their young daughters off to people with consistent food and a home to offer.

In sum, Bangladesh, much like Malawi, is paying the price for sins it did not commit.

During our mutual layover in Bahrain, Chandra Pal gifted me a clay turtle figurine, a woven wallet, and a book of poems he had written. The book, entitled The People Will Rise Again, is a “call to everyone to rise up once again for nature against transgressions.” It takes a hopeful tone, noting the beauty of Bangladesh, the injustices waged against its land and people, and, finally, the power of the people to rise up.

In Chandra Pal’s words, “It is hard to breathe now” (Chandra Pal 60). Yet he finds hope. His hope lies not necessarily in the systems, the motivations of which he questions (Chandra Pal 63), but in the people themselves. He has faith that the people can dry their tears and use the hurt—the fury—of the crimes committed against them to drive change. As he professes,

Tears have clustered and turned hearts into stones,

Bearing pain in silence, this world is searing in defiance

So, people will rise again, throbbing and thrusting,

Standing against transgression (Chandra Pal 20).

Chandra Pal did not view COP29 as a failure. On the contrary, he pointed out to me some of the conference’s many successes. As he notes, the people, when banded together, have the power to “rise up with humanity and conscience” to bring “life…back” from “city to village” and “mountain to lagoon” (Chandra Pal 21).

Chandra Pal is not alone in this sentiment of faith in the people at COP29. On day six of the conference, I visited the Regional Climate Pavilion for a talk on the philanthropic structure of climate finance led by a consortium of philanthropic funds run by and for the Global South called Alianza Fondos del Sur. After a quick simulation on effectively implementing project funds, we sat down in a circle and Florentina, an indigenous woman from Ecuador, spoke to her experience at COP29.

In her village, accessible only by plane or boat, the work women are expected to do is getting increasingly dangerous as the climate warms. Florentina has spent years fighting for the security of the local forest and confronting violence and insecurity for her community but had felt isolated in this work, both physically and socially. A Costa Rica-based philanthropic organization called Fondo Tierra Viva had noticed her work, however, and funded some of her projects in her community, even badging her and flying her out to Baku. Her words, translated from her indigenous dialect into Spanish, affirmed the goals of COP. Locking eyes with her translator, she shared that she had thought she was alone in confronting climate change but now, surrounded by tens of thousands of people from around the globe purportedly fighting for the same goal she was, she felt a sense of kinship and solidarity. She paused and looked at each of us around the circle, most wearing headphones to translate the Spanish into their own languages. Together, she said, we can make the world turn and listen to what is being asked in these spaces.

The type of broad uprising Florentina and Chandra Pal suggest here, though perhaps ambitious, is not unheard of in UNFCCC spaces. Filippino historian and UNFCCC Board of the Peoples Survival Fund member, Renato Redentor Constantino, writes about one such instance. In 2015, he wrote in his essay entitled “How the Ants Moved the Elephants in Paris,” powerful countries in the Global North attempted to stifle ambition and ignore science by gearing towards a two-degree Celsius warming limit for the now-famous Paris COP21 text despite 1.5 degrees being the agreed-upon “maximum allowable rise in average global temperatures” (Renato Redentor Constantino 73, 2015). The half-degree gap here represented, for many developing countries, the “difference between survival and annihilation” (Renato Redentor Constantino 74, 2015).

Countries belonging to the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) rose up against “tremendous efforts” to keep the 1.5 number in the text (Renato Redentor Constantino 73, 2015). By exacting a global campaign convening senior ministers from across the Global South and leveraging various groups’ optics-oriented desires to ally with developing states, the “ants moved the elephants” and the gavel landed in favor of the “ultimately doomed” threshold of 1.5 degrees celsius (Renato Redentor Constantino 73, 80, 2015).

At COP29, the people rose to get civil society in the doors in Baku. In a note in the COP29 observer handbook, UNFCCC Executive Secretary Simon Stiell noted that the number of observer badges would be reduced, a decline he blamed on a “reduction of space.” He claimed that the decreased quantity would be doled out in a “more balance[d]” manner in the “spirit of global solidarity,” a largely celebrated move to include more observers from the generally underrepresented Global South. This motive was questioned, however, when civil society organizations (CSOs) from these countries did not see an increase in badge allowances: rather, it seemed, all of civil society—and, notably, nations that have expressed disapproval of Russia’s actions in Ukraine—had seen reductions (Hautzinger 2024).

The elephants—as Redentor Constantino would say—had played their cards right, leaving the ants with insufficient space to pressure negotiators, share their knowledge, network, and represent unheard voices. But, in what Australian PhD candidate Isabelle Zhu-Maguire calls “a testament to the fortitude of civil society,” the people rose above. My own ten-person delegation, who initially was awarded only one badge, traded and maneuvered with other organizations until all eight student delegates were badged for at least 11 days (Hautzinger 2024). Other Early Career Researchers (ECRs) I met in a post-COP29 virtual debrief had similar experiences: one had been badged by four different organizations during her time at COP and another noted that she had emailed the designated contact persons (DCPs) of over four hundred observing delegations in order to compile her badges for the conference. The people had banded together, utilizing a sprawling network of observing delegations to get people past the open-access green zone and into the rooms where decisions were being made.

Some of the more seasoned veterans of COP—anthropologists Naveeda Khan (2023) and Sarah Hautzinger, to name two—don’t identify with the term ‘hope.’ It feels naïve and, in some ways, complacent. But the type of hope that Chandra Pal and Redentor Constantino talk about is not a passive, complacent hope. Their hope is a catalyst, one that allows representatives of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) to pressure “the powerful” into adopting the necessary 1.5-degree warming limit. To them, hope is “complicated but necessary,” a way to “embrace uncertainty” without succumbing to “defeat and despair” (Redentor Constantino 80).

This paper does not intend to answer in any conclusive manner the question of whether COP is still viable in its current format or whether no deal would have been better than a bad deal. It intends, rather, to examine the ways that hope and dismay presented themselves at COP29 in the crucial two weeks that exposed the flaws in our existing systems. It intends, too, to highlight some of the positives at a time when it is so easy to get stuck in grief. At this moment when the UNFCCC process as a whole has come into question, we can either use our disappointments, frustrations, and hopes to galvanize a seismic shift in global climate action or sit, complacent, stewing in our fury. Our loyalty must lie with the planet and its inhabitants rather than with an institution.

The words Redentor Constantino drafted in 2015 still ring true today: “The obstacles to action are essentially purely political” (Redentor Constantino 80, 2015). As we near COP30 and reflect on the failures of COP29, we must keep in mind the successes of the COP and the power of the people. But we must listen, too, to the voices telling us we are not doing enough.