By Laurie Laker ’12

Colorado College Professor Emeritus of Political Science Bob Loevy (as he says, “rhymes with navy,”) has been associated with the college for five decades. In that time, he’s impacted thousands of students, generations of local and state politicians, and reshaped how elections are conducted and cultural movements covered. It’s been quite a life, and Loevy is showing no signs of slowing down, remaining incredibly active in his writing, community engagement, and political involvement.

Colorado College Professor Emeritus of Political Science Bob Loevy (as he says, “rhymes with navy,”) has been associated with the college for five decades. In that time, he’s impacted thousands of students, generations of local and state politicians, and reshaped how elections are conducted and cultural movements covered. It’s been quite a life, and Loevy is showing no signs of slowing down, remaining incredibly active in his writing, community engagement, and political involvement.

Born on February 26, 1935, in St. Louis, Missouri, Loevy spent the first third of his life in Baltimore, Maryland. His father’s company was bought by a firm in Baltimore in 1940, and so the Loevy family exchanged baseball Cardinal red for Orioles orange and moved east.

“I’m more of a Baltimorean and an East Coast type than I am anything else,” says Loevy in his North Nevada Avenue office. Moving when he was 5, Loevy would call the Charm City home until he was 33 years old. First, attending St. Paul’s School, an independent and private day school, Loevy then left for four years of undergraduate education at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, graduating with his B.A. in political science in 1957.

“My time at Williams exposed me to a wonderful, excellent undergraduate education,” says Loevy. “The college did not enjoy the stellar reputation then that it has today, but it was definitely a good school. I was lucky that I found a home, eventually, in the Political Science Department there.”

From that second home, Loevy returned to his first, to Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University for his master’s and doctoral pursuits, both in political science, finishing in 1959 and 1963, respectively. Loevy can recall the precise point in his life when politics first became an interest.

“I was a sophomore in high school, and read ‘All The King’s Men’ by Robert Penn Warren. I’d seen the movie but somehow the book appeared in our house. I picked it up, read it, and decided that politics would become my main interest,” Loevy recalls.

“At Williams, my focus was mainly on international relations, because I had a very powerful professor called Frederick L. Schuman. At grad school, I had to work my way through as a newspaper reporter for the Baltimore News-Post and American, cruising one of the great working-class cities of America.”

Loevy’s career as a reporter intersected with one of the most uproarious and momentous times in American history. Alongside his City Hall beat and reporting on various city police districts, Loevy found himself covering the civil rights movement that was bubbling up and boiling over across the country. “It was my job to witness and report on what was going in the Baltimore area, and a huge part of that was the civil rights movement. I was on the edge of a race riot in Cambridge, Maryland, where the governor sent in the National Guard at the last minute to prevent a crisis.”

“Maryland is a ‘border state’ — it had had slavery but had not seceded from the Union as a part of the Confederacy; so, segregation was always there. From the time I was there, Maryland went from completely segregated in every way to integrated,” he recalls.

Loevy began moving away from journalism and toward the behind-the-scenes workings of political news, teaching a night course during his second year of graduate school, and then starting a year later at Goucher College to teach political science.

“My department chair at Goucher handed me a flyer one day that said Congressional Fellowship Program, on it — a high-powered fellowship for young political science teachers. It was an eight-month placement to work in Congress, spending four months in the U.S. House of Representatives and four in the U.S. Senate. I applied and won the fellowship in 1963.”

“My department chair at Goucher handed me a flyer one day that said Congressional Fellowship Program, on it — a high-powered fellowship for young political science teachers. It was an eight-month placement to work in Congress, spending four months in the U.S. House of Representatives and four in the U.S. Senate. I applied and won the fellowship in 1963.”

In the summer of 1963, Loevy made his way 40-odd miles south, to Washington, D.C., found a place to live, and went to work on Capitol Hill.

“It’s one of the great fortuitous events of my life,” reflects Loevy.

“Having covered the civil rights movement as a reporter, I now was assigned as a legislative assistant to U.S. Senator Thomas H. Kuchel of California, who would be named the Republican Floor Leader for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

“I was able to go to all the meetings for the legislative assistants helping senators break the filibuster around the Civil Rights Act. I was an observer on the floor of the Senate when the Civil Rights Act was passed. I was at the White House when Kennedy was pronounced dead in Dallas — I heard on the Secret Service radio, ‘President Kennedy has been shot, all units proceed to protect President Lyndon B. Johnson.’ ”

Such an impactful political front line experience, when blended with a passion for teaching, pointed Loevy toward academia. A long-standing connection to several other icons of Colorado College soon pointed his life and career westward, to Colorado.

“When I was teaching night classes, another Johns Hopkins student — Timothy Fuller — was my paper grader,” Loevy remembers. Timothy “Tim” Fuller is, of course, the professor of political science who has taught at the college since 1965.

“I also knew Glenn Brooks, who was a friend of mine while I was at Johns Hopkins — in the cohort ahead of me. I knew he got a job at Colorado College once he’d finished in Baltimore. When I learned Tim Fuller was going to Colorado College, I said to him, ‘That’s wonderful, you know someday I’d like to spend some time in the Rocky Mountains. I’ve spent my whole life on the East Coast; it would be nice to go out there some time.’”

Brooks, now a fellow professor emeritus of political science, taught at CC for 36 years. He is widely known as the father of the Block Plan, and served as dean of the college and faculty for eight years.

Brooks, now a fellow professor emeritus of political science, taught at CC for 36 years. He is widely known as the father of the Block Plan, and served as dean of the college and faculty for eight years.

Fortuitously for Loevy in 1968, a job opened up. “Tim Fuller got ahold of me, I applied and came out to interview, and I began teaching at Colorado College in the fall of 1968.” Loevy would remain teaching at the college for 43 years.

“I noticed right away that there was a difference in the focus of the college at CC; the students were the center of all activity on campus. That was evident in faculty meetings, conversations, and everything else,” remembers Loevy.

“I’d found Williams colder than Baltimore, and I found CC far warmer than Baltimore — my wife and I were welcomed in every way possible by faculty and students, the faculty here being far more social. The entire atmosphere of CC — academic and professional — was completely different from anywhere else I’d been.”

Coming from the rigors of Capitol Hill and Johns Hopkins, Loevy encountered another kind of rigor in his early years at CC — the Block Plan, first implemented at the college in 1970.

“I had more of an adjustment to make than others, I think,” Loevy says of those early days.

“I had extensive teaching experience prior to coming to CC, and I’d patterned my teaching after Dr. Schuman at Williams, who taught in a formal lecture style that allowed some interruption and discussion. From that style, I had to tone things down when classes got smaller — the 25-student limit cap was the hardest to adjust to — I had to dial down the lecture components and build up conversation and dialogue.”

The intensity and pace of the Block Plan require as much from the faculty as it does of the students. Time and dedication aren’t always enough, and flexibility in and out of the classroom remains of paramount importance to a successful and fulfilling CC experience.

“As the Block Plan requires, I had to sharpen my skills in listening and talking with students, not at them, I had to guide discussion rather than simply giving lectures and answering questions,” Loevy says.

“When you have a small class, you’re all those students have. All that they learn and take away from that class is on you, the professor — that’s the most important part of teaching on the Block Plan, what it was designed to do. Colorado College was the only place that the Block Plan could emerge and flourish. It could only have happened here.”

Flourishing in the classroom led to a flourishing beyond.

“My wife and I had a family, a boy and a girl, and I was involved heavily on campus in committee work, teaching Summer Session, organizing and teaching in an Urban Studies Institute for 13 summers,” says Loevy.

Writing and publishing his research came into play later in his career, and has remained a core component of his life ever since.

“Until 1980 or so, I didn’t emphasize writing much at all. I was far more of an on-campus player. Everyone always says to write what you know, and what I knew was the Civil Rights Act of 1964. There’d never been an academic book on it before, so that was my starting point.”

That starting point would eventually become Loevy’s first book, published in 1990, “To End All Segregation: The Politics of the Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Arguably the definitive legislative history of the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the book is written with Loevy’s insider lens at the heart of the narrative.

From the Civil Rights Act, Loevy’s writing and research took him into presidential primaries.

“Those works are the result of what academics are supposed to do; sitting in my office in Palmer Hall, having an idea,” Loevy recalls.

“It occurred to me that there had never been any kind of reformist literature about presidential primaries, offering critiques of the primaries system and possible solutions. Ultimately, it led to four books in total, as well as a huge professional commitment outside of writing as well.”

This professional commitment that Loevy alludes to is his key role in Colorado’s first presidential primary in 1992. In 1990, Loevy wrote a memo for then-State Senator Mike Bird that outlined a primary date and how the delegates should be apportioned, as well as the dimensions and requirements for all candidates and delegates. The memorandum became the foundation used by Colorado lawmakers to draft the state’s first presidential primary legislation.

“In the middle of all of this, Tim Fuller came to me and asked me to write a book to mark the 125th anniversary of Colorado College. I was more than happy to take that job on,” Loevy says.

That book, “Colorado College: A Place of Learning 1874-1999” along with the followups “Colorado College: 1999-2012, into the 21st Century” and “A Colorado College Reader: Selected Writings on the History of Colorado College” capture CC’s history, from its founding into the modern era.

“The Reader is my favorite book about not just CC, but about any college,” Loevy says. “I’ve never seen a book made up of various essays by all four categories of people associated with the college — alumni, faculty, staff, and students. It was a three-year project, and by far the most fun I have had on a book, so far.”

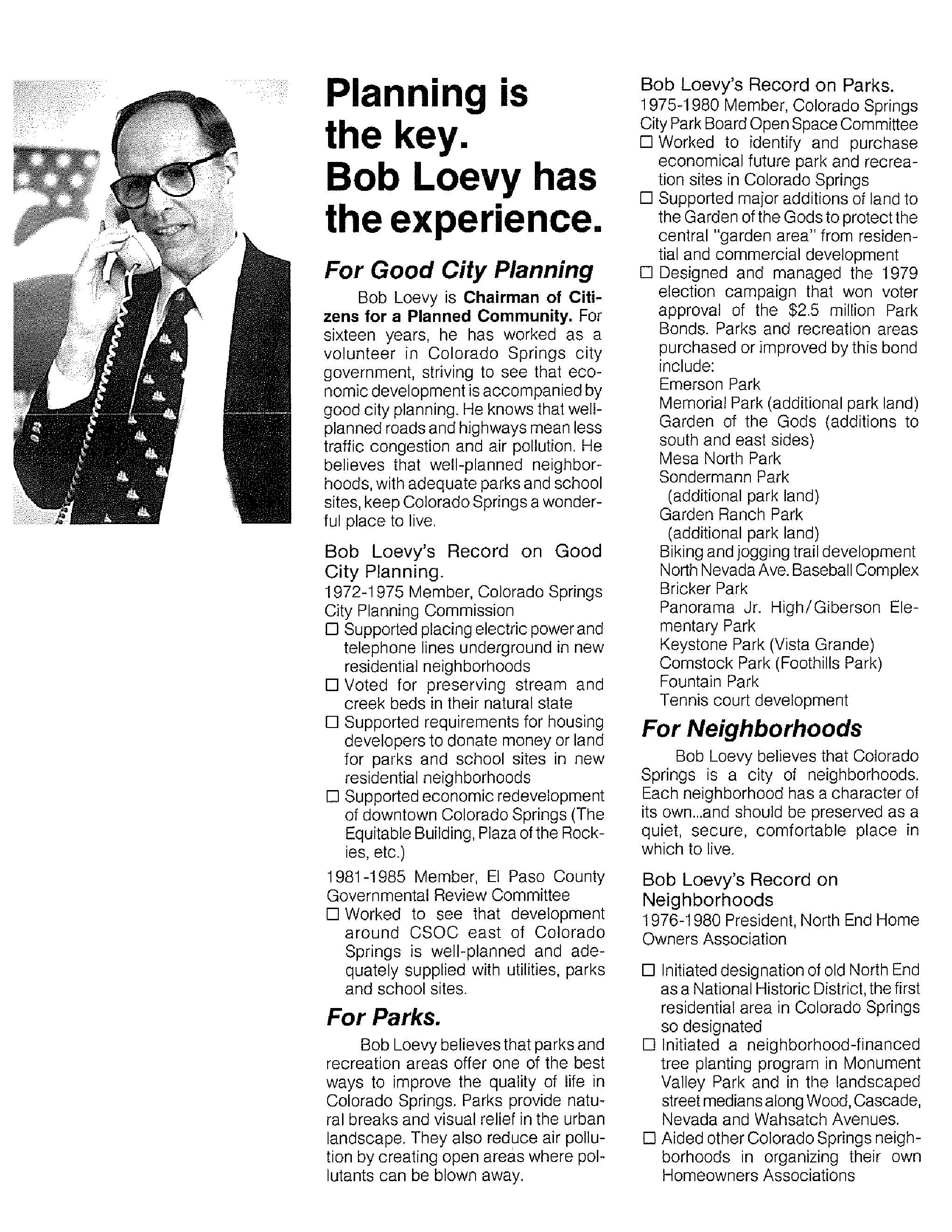

Beyond teaching, being an expert on the presidential primary system, speaking to political national committees, raising a family, and writing nearly a dozen books, Loevy has also been a linchpin of the Colorado Springs community.

He served on the Colorado Springs City Planning Commission from 1972-1975, was a member of the Colorado Springs City Charter Commission, the chairman of the Colorado Springs Open Space Committee, and has served as the president of the Old North End Neighborhood association. Loevy also ran unsuccessfully for City Council twice, in 1987 and 1991, prioritizing parks, infrastructure, and a strengthening of homeowner’s rights in the neighborhoods of the city.

Loevy retired from full-time teaching during the 2010-2011 academic year, at the age of 75.

Loevy has not slowed down, despite the fact that his progressive muscle disease had picked up speed by the time retirement came around. In 2011, Loevy was tapped as a crucial member of the Colorado State Reapportionment Commission, which meets every 10 years to reconfigure and rework the electoral district boundaries for state Senate and state House seats using U.S. Census data.

“Someone, an unknown person to this day, put forward my name to be on the commission. Swing seats were a key component of the work we did, and became a theme of redistricting across Colorado today. That commission work was basically full time in 2011, and it was a dream job for a retired political science professor like me,” recalls Loevy.

Loevy wrote an online book about his time on the committee, “Confessions of a Re-Apportionment Commissioner,” which has been cited by numerous groups and committees working on the recent redistricting overhaul across Colorado.

“That my work has been taken to the people and adopted by the voters; it’s a great way to spend retirement,” says Loevy. Other retirement projects have included historic-looking street-name signs for the Old North End, the 100-year-old neighborhood north of the college where Loevy lives. He also helped install six stone entryway signs for the Old North End, and he worked with both the Old North End and the college to narrow Cascade Avenue to only two lanes of traffic, both through the college as well as the neighborhood. Loevy recently has lobbied the college to make the new Robson ice arena have a red brick color resembling Armstrong and South halls.

5 Responses to Professor Emeritus Robert D. Loevy

I took one of Bob Loevy’s poli-sci classes in 1970. In that class, he assigned us a project to write a simple computer program to analyze election results. It ran on the then new Hewlett Packard mainframe. That programming experience ignited my love of computers and programming. After CC, I went into engineering and extensively used computers early on. I also wrote most of the software my company has used since the ’80s. My career and working passion stems directly from Bob Loevy’s foresight in predicting the importance of computing in everyday life. Thanks!

Bruce Davis ’73

A great professor and colleague. We share offices on Nevada.

Bob Loevy was THE professor who inspired me on to a career of public service. From his first days at CC designing a course in urban planning to being my advisor and mentor on the Ford Foundation Venture Grant I received (first one given by CC), Bob was an inspiration.

I have been a deputy mayor of a major urban city – Indianapolis, advisor to governors and a special judge for the Indiana Supreme Court. I directed a public policy institute at Indiana University and taught mediation and dispute resolution at IU McKinney School of Law and IU O’Neil School.

My regret is that others could not be as fortunate to have Bob Levy in the classroom and as a friend.

My best wishes to him. He is a major reason that CC had an impact on my life.

Dr.Loevy was my major professor. I enjoyed his perspective and dry wit. He really challenged his students to think outside the box, which empowered me throughout my career.

Great article!!

Ellen Watson, CC Class of ‘75

I was part of Professor Loevy’s first urban studies summer session in 1969 which I recall had a focus on resort sprawl that was beginning to take over Colorado ski country. Of course, we had to visit the sites, so spending some time in Aspen and Vail in the summertime was extra special.

The article highlighted many of Bob Loevy’s attributes including his own words about adopting to the block plan way of teaching with more student dialogue replacing lectures. That’s exactly what I remember happening in his first summer session. There was a new energy in the classroom, so Bob was a natural for the Block Plan start up the next year.

Certainly an inspiration for me as I went on for a 31 year career in land use planning.

Jim Claypool ‘72