By Scott Broadbent

Water issues have recently emerged as a hotspot for environmental justice in Colorado for many reasons including the relative scarcity of water in the arid Southwest, the extremely complex system of water rights in the region, and the history of extractive industry (mining and fracking) polluting drinking water supplies, among others. Drinking water is of serious concern to environmental justice because, especially in the southwestern United States, uncontaminated drinking water has become decreasingly available to low-income communities, minority communities, and tribes. The plights of these communities are often ignored due to their lack of political power, their inability to represent themselves, and the absence of economic motivations to do so. Here I will provide you with a case study in water contamination that demonstrates the complexity and injustice surrounding this issue.

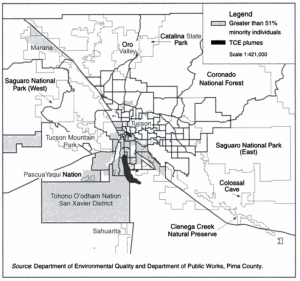

Tucson, Arizona is a city with a large Hispanic and Latino population. The most recent census data shows that more than one third of Tucson’s population is Hispanic or Latino. The area surrounding the Tucson International Airport has especially high concentrations of Mexican-American families. You can visualize this for yourself by going to http://www.city-data.com/nbmaps/neigh-Tucson-Arizona.html and clicking around on the interactive map (TIA is located in South Tucson.) Corporations and city officials capitalized on this fact to get away with dangerous and unlawful acts for decades. Let’s cut to the chase.

In 1951, Hughes Aircraft (now owned by Raytheon) was contracted by the United States military to build missiles at a newly constructed plant on lands recently purchased from the Tucson Airport Authority. The company used multiple toxic chemicals in their manufacturing process and throughout the years simply dumped those chemicals in dry streambeds (arroyos) and unlined holding ponds in the area surrounding TIA. These toxins seeped into the ground and then into the groundwater, contaminating the local aquifer. As if this unchecked environmental degradation were not horrible enough, these toxins began having deadly health effects on the people living around the airport.[i]

Trichloroethylene, or TCE as it is commonly abbreviated, was one of the major chemicals used at Hughes Aircraft. It is now known that other parties were using TCE as well, including the Air National Guard and Tucson International Airport itself. TCE is a volatile organic compound that has been shown to be correlated with neurological disorders, kidney failure, cardiac defects, oral clefts, fetal deaths, and cancer. On Evelina Street in Tucson, less than one mile from the airport, 34 cancer cases have been documented to date[ii]. There are currently several families on Evelina Street with only one surviving member. Residents of Southside Tucson had been complaining of chemical smells and tastes in their water for years before the EPA finally tested the water in the area of TIA and found it to be contaminated.[iii]

A map of Tucson indicating how the plume of TCE contamination was located in predominantly minority neighborhoods. (Source: De la Peña)

The official response to this contamination has been less than ideal. In one instance, the Health Director of Pima County told an audience of mostly Hispanic people that the high rates of cancer and death in their neighborhood were because their diet was bad, they smoked, drank too much, and did not exercise enough. In 1991 the City of Tucson government released a report declaring that “with minor exceptions, no remarkable hotspots were found… any efforts to convince scientists or others that further studies are in order must contend with this ADHS clean bill of health for the neighborhood.”[iv] The report can be found here: http://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/environmental-toxicology/tucson-int-airport-2001.pdf.

These examples demonstrated that not only were government officials aware of the problem, they were dedicated to sweeping it under the rug. In 1987, 1600 residents of Southside Tucson sued Hughes Aircraft, the United States Air Force, and the City of Tucson for their personal injuries caused by water contamination.

Their case was fought through 15 years, two trials, three appeals, and two favorable decisions by the Arizona Supreme Court. The case concluded in June 2006 after the city and Hughes Aircraft both settled with the residents, netting them over $130 million dollars. This case is a powerful reflection of how the civil rights framework can be used in litigation to give power to the powerless. To quote Richard Gonzales, one of the lead attorneys on the case, and a resident of Tucson –

“I remember growing up on the South Side. We never had any political muscle and never exercised a voice in government. There was an entrenched sense that the South Side was powerless to look out for their interests.”

Thanks to civil rights and environmental justice, the residents of South Side Tucson are powerless no more.

[i] Pinderhughes, Raquel. “The Impact of Race on Environmental Quality: An Empirical and Theoretical Discussion.” Sociological Perspectives 39.2 (1996): 231-48. Web.

[ii] EPA. TCE Contamination, Exposure, and Cleanup, Tucson, AZ

[iii] https://baronandbudd.com/environment/water-contamination/tce-tucson-arizona/

[iv] http://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/environmental-toxicology/tucson-int-airport-2001.pdf

De La Peña, Nonny. “Fighting for the Environment.” Hispanic (1991): 18-13.