A Case of Public Participation

It is widely thought that a useful tool in the fight for environmental justice is increasing the public involvement of previously disadvantaged communities in the political processes surrounding the management of the environments they live in. While most agree it is a necessary first step in the fight for environmental justice, the extent to which public participation can be effective is still disputed[1]. Contentions surrounding the existence of an open pit gold mine located in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in southern Colorado provide an example of the limits of public participation.

According to the United States Census, as of 2000, the town of San Luis contained 739 residents, 253 of which lived below the poverty line and over 88 percent were of Hispanic or Latino descent. In San Luis, several irrigation ditches and their accompanying water rights have been owned and managed through community cooperation since before the state of Colorado existed. The majority of stakeholders, or parciantes, in these acequias, as the ditches are called, near the town of San Luis, have kept the rights and responsibilities of the water they use to fuel their farms within their families to this day[6].

Initial Disputes Over the Mine

In the late 1980’s Battle Mountain Gold Co., a Houston based mining firm, began the process of creating an open pit gold mine roughly five miles away and directly upstream from the town of San Luis[3]. In order to operate, the mine needed a permit to augment the downstream water rights of the San Luis People’s Ditch, a downstream acequia. Concerned over the possibility of the mine contaminating the source of water for several of the acequias, and the destruction of previously communally used land, the citizens of San Luis strongly objected to the mine proposal[6]. Their opposition took the form of speaking out at county hearings, contacting local and state politicians with their opinions, taking Battle Mountain Gold to court and forming the Costilla County Committee for Environmental Soundness[4]. Despite the multiple avenues of public participation they utilized to voice their disapproval, the Rito Seco mine was approved at the federal and state levels, and began operation in 1992[4].

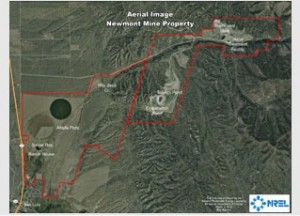

This aerial photograph from Water and Environmental Justice: Acequias in Colorado – Part 1 of 3 shows the Rito Seco mining operation toward the top and right and the town of San Luis in the bottom left corner[4].

The Period of Contamination

In the fall of 1998, just two years after the closure of the mine, the tailings pile began to leak numerous dangerous chemicals into Rito Seco Creek. Officials from the State Division of Minerals and Geology had ordered the company to obtain a discharge permit, as they did not have any permission to allow any discharge from the mine into the creek[2]. The company was allowed to ignore this order by the state for over a year until the EPA was able to go through the process of testing, examining and deciding that this seepage was in violation of the Clean Water Act[2]. After receiving an order to cease and desist, the company was required to build a water treatment plant for the contaminated water coming from the mine, which they did[2]. During this time period, citizens downstream who found out about the contamination voiced their opinions to the appropriate state and federal organizations, as well as to the company, but were left powerless to address the health hazard in their water through any further form of public participation[6].

After the order was received from the EPA, Battle Mountain Gold company employees and state officials met with county officials in private in order to inform them as to the details of the contamination and the plan for addressing it. The Costilla County Conservation District, an entity representing the interests of the citizens opposed to the mine, sued the county commission board for violating Colorado’s Open Meetings Law. The court found that no law was violated as no policy was being created, simply information was being shared by the state agencies and Battle Mountain Gold Co[1]. This court case represents an attempt by the affected citizens to increase their ability to participate in the sharing of information by and resulting decision making of government and company officials.

The Inadequecy of Public Participation

Since the company has addressed the water contamination issue, their operation is once again completely legal and they have been allowed to return to their reclamation process that the people of San Luis continue to oppose. This case is clearly an illustration of the inadequacies of the public participation framework for addressing issues of environmental justice. While the disadvantaged majority Hispanic community in San Luis has been active in opposing the mining and reclamation operations of Battle Mountain Gold in various ways, the company has still been able to run an operation that clearly poses hazards to that community. The ability to be included in the public process has rightfully given a voice to the downstream acequia community, however it still has not done enough to protect them. This illustrates how working within our current economic and political system will not result in the level of environmental justice that is truly just. To achieve this goal, alternative frameworks of environmental justice, such as the creation of basic rights to a clean environment and the inclusion of ecologically sustainable practices in our economic philosophies, must be pursued in addition to increased public participation.

- “BD. OF CTY. COMM. v. COSTILLA CTY. CONS. DIST, 88 P.3d 1188 (Colo. 2004) | Casetext.” N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

- Martínez, Maclovio. Potter, Lori. Flynn, Roger. “OHBC News Releases.” 11 Aug. 1999. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

- Shore, Sandy. “Gold Mine Stirs Debate Over Environment and a Way of Life.” Los Angeles Times 8 Mar. 1992. LA Times. Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

- Peña, Devon G. “Water and Environmental Justice: Acequias in Colorado – Part 1 of 3.” 3 Apr. 2013. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2016.

- Torres, Gerald. Justice and Natural Resources: Concepts, Strategies, and Applications. Island Press, 2001. Print.

- Pena, Devon Gerardo. Chicano Culture, Ecology, Politics: Subversive Kin. University of Arizona Press, 1998. Print.