A short film by Paper Rocket Productions documenting testimonials of the San Carlos Apache and their allies about the proposed mine at Oak Flat.

In the Southwest, water is a scarce resource. It is not hard to imagine why the people of the region would hold their water not just as essential, but as sacred. Since their internment onto reservations, indigenous nations of the Southwest have seen their water rights increasingly diminished as well as the poisoning of sacred lands and waters. The effects of climate change compound this situation, which stand to make water an even scarcer resource for the coming generations. This is a topic of vital importance in modern Southwestern environmental justice. As a minority, and often impoverished, population with a history of systematic oppression, Native Americans serve as a prime investigatory group for environmental justice. Native peoples in the Southwest have struggled for centuries with water rights, contamination, and access to sacred waters, and the case of the San Carlos Apache at Oak Flat is no different.

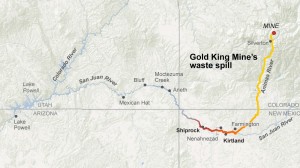

Across the entire United States, government and private industry has desecrated sacred waters. In the Southwest, most problems revolve around contamination from mines, contested water rights, as well as flooding of sacred places due to the West’s obsession with stockpiling water. Many environmental justice cases in the Southwest involve water, the most sacred resource in the region.

“We grew up learning a tradition of respect for water, hearing our Elders praying with water. Water is a part of every second of our lives, everything has water flowing through it, everything has life.” –Crow leaders

In 2014, Senator John McCain (R, AZ) hid a land swap inside a 2,000-page military budget after it had failed to pass as a standalone bill multiple times. The tactic of hiding controversial deals in large, must-pass bills has been used for decades; when Congress passed the bill, the land swap was also approved. The deal traded 2,400 acres of Oak Flat, a federally owned portion of land, for 5,000 acres of land owned by mining company, Resolution Copper. At first glance, it seemed like a good idea: Arizona gained more than double the amount of conservation land they gave away. As in any controversial deal, however, it was not so simple.

Oak Flat is a portion of the Tonto National Forest in Arizona that borders the San Carlos Apache Reservation. It is home to holy waters important in Apache religious ceremonies as well as historic sites and artifacts that are thousands of years old. It also sits on top of the largest copper ore deposit in North America. Senator McCain proposed the land swap so Resolution could mine the copper at Oak Flat. The mining will cause an area of over a mile in diameter to sink 1,000 feet into the ground while covering even more land with rubble and waste. The mine will cause contamination of the local watershed, including polluting the entire aquifer located under the deposit. This would destroy the Apache’s sacred waters: waters on which they have subsisted and have used in religious practices for millennia.

Many people oppose this deal. In fact, it was struck down twice in Congress before McCain was able to sneak it into another bill. Besides Native Americans, the list of critics includes the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, many politicians, public lands workers and advocates, archaeologists, and even local miners! The main three concerns are that 1) it will destroy sacred Apache sites and artefacts, 2) it will damage the (once) public National Forest land and will contaminate the aquifer and surrounding watershed, and 3) it sets a dangerous legal precedent in which Congress can just give away public lands with little oversight. In addition, the deal included conditions to bypass important parts of the required environmental and cultural evaluations, making it seem impossible to stop the mine.

“If there’s one thing we do all have in common it’s that we respect the Earth, and we are all fighting for our land.” – Wendsler Nosie Sr., San Carlos Apache Tribal Councilman

The Apache and Native American rights groups are the strongest objectors of the Oak Flat deal. The San Carlos Apache consider this land holy and require its existence to practice certain aspects of their religion. They have occupied the lands for thousands of years, but since Oak Flat is just outside reservation boundaries, the Apache have no legal claim to the land. This is a type of legal battle Native tribes across the country have struggled with since the inception of the reservation system. In the 1800’s, the American government forcibly removed the native peoples to the San Carlos Reservation and forced them to sign a treaty relinquishing the land using military force. The Apache did not willingly give up their ancestral homeland, but are now constrained in protecting it by these unjust laws and treaties. These cases disproportionately affect Native Americans who have little economic or political clout due to systematic oppression that has been institutionalized since the first arrival of Europeans on American soil.

“Would (you) have this same position if an ore body were to be located beneath (your) church … and a company wanted to bulldoze or destroy it?” –Terry Rambler, Chairman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe

The United States Constitution guarantees the freedom to practice one’s religion. It also guarantees that no private property shall be taken for public use without just compensation. Furthermore, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that indigenous people should have rights to their traditional lands and resources, even if they are currently held by another party (in this case, the U.S. government). In the Garma International Indigenous Water Declaration, indigenous peoples, including Native Americans, assert that scared waters are an integral part of their physical, cultural, and spiritual existence and they have an inherent right to them. These rights have all been violated by the careless trading and disrespectful and destructive proposed use of Oak Flat.

The San Carlos Apache have been protesting this gross injustice against their lands and waters for the past two years. Currently, some small steps have been taken to stop Resolution Copper. The National Park Service placed Oak Flat on the National Register of Historic Places, which will make it harder, but not impossible, to start the mine. Senator Bernie Sanders (D, VT) also introduced a bill to Congress in 2015 to stop the swap, but it has not yet been addressed. The San Carlos Apache continue to try to protect their ancestral holy waters, but they need your help. Write a letter to your senators and tell them that both the environment and Native American rights should be respected and to #SaveOakFlat.

More Cases of Native American Water Injustice:

Years after mining stops, uranium’s legacy lingers on Native land

Rainbow Bridge, Utah – Tsé’naa Na’ní’áhí

Navajo water supply is more horrific than Flint, but no one cares because they’re Native American