Photo by Konrad Flæte Gundersen

By: Konrad Flæte Gundersen

______________________________________________________________________________

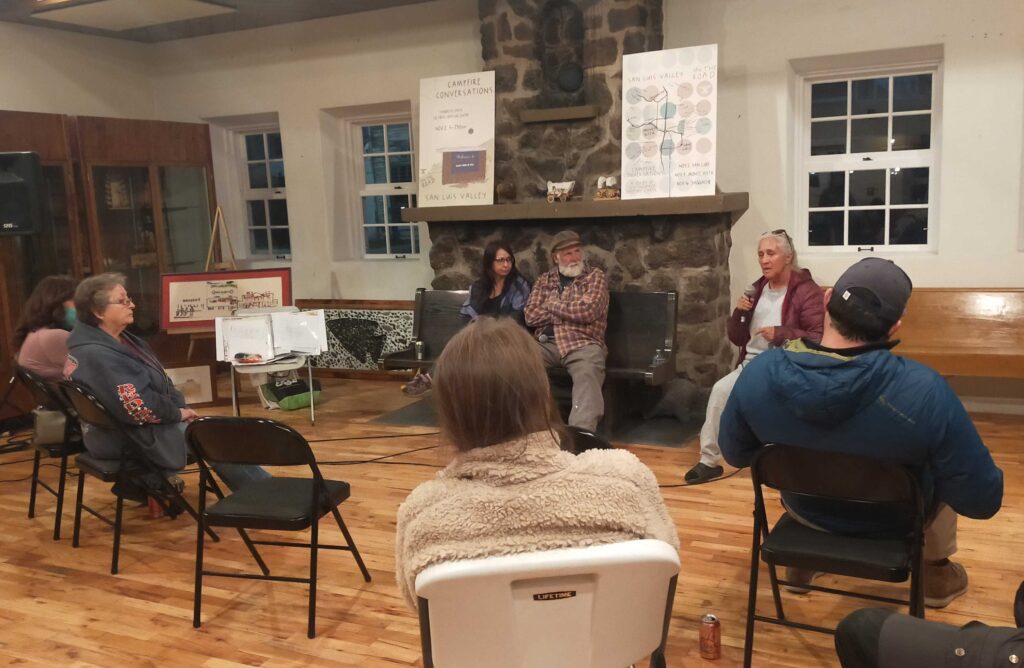

SAN LUIS – On a recent chilly evening at dusk, elders here in Colorado’s oldest town gathered at a schoolhouse converted into a museum and held an intimate meeting, drawn together by their families’ generations of experiences, sharing their love for this place at the base of the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

They savored tacos made with blue-corn tortillas and jokingly debated how a true tortilla should be made. Farmers, teachers, activists, caregivers, cooks and a sculptor who established the San Luis Stations of the Cross along a hillside trail spoke one by one about the things that matter to them most.

They talked about their “acequias,” a system of locally regulated irrigation ditches that date to inherited Moorish practices for rationing sustainably the water that runs off the mountains. They reminisced about family outings on the mountainsides – communal terrain for centuries under a Spanish land grant allocation – where women gathered fruits and nuts and men hunted deer, fished and collected firewood for heating their adobe homes. Laughter, smiles and mutual respect pervaded this community conversation.

But incursions by an outsider billionaire added a sinister dimension. Billionaire William Harrison of Texas has purchased a 130-square-mile area that includes all that mountainside land and 19 Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) mountain peaks – a property that he has renamed Cielo Vista Ranch. Harrison has declared his intention to install an 8-foot fence and establish a herd of bison on his property.

“Most newcomers come in with the notion that land and water are a commodity,’’ Shirley Romero Otero, co-founder of the San Luis Land Rights Council, said in the meeting. ‘’Land and water is sacred.’’

Photo by Konrad Flæte Gundersen

The threat that San Luis residents could be excluded from their cherished terrain, the disruption of communal norms, and possible harm to existing wildlife is creating havoc here – again. Jack Taylor, a North Carolina timber baron and previous owner of the ranch, once hired armed guards to keep residents out — until they fought a two-decade legal battle and won the right to use the land for grazing, timber and collecting firewood.

The San Luis Valley stands out as Colorado’s lowest-income area with more than a fifth of residents living in poverty. It is one of many scenic areas in the Rocky Mountain West where billionaires threaten to displace working people.

“We call ourselves culturally rich and financially poor,’’ said Charlie Jaquez, a retired teacher and Vietnam war veteran who once led classes in the museum and heritage center where the elders had gathered.

In recent decades, the San Luis Valley has seen an influx of wealthy landowners. Meanwhile, passionate long-time residents who are intent on protecting their traditions – and maintaining access to land and water – bristle at incursions by people who hunt for recreational purposes and sometimes seem to want to appropriate a culture that isn’t their own.

“My biggest concern is the gentrification and taking of water,’’ Otero said in the meeting.

Otero, Jaquez and other attendees said they fear displacement as wealthy outsiders buy up surrounding private property. They’re especially skeptical of Harrison.

He is the chief executive of a corporation called Cathexis, ‘’a multi-strategy holding company,’’ according to the Mass Investor database. The corporation has investments in construction, energy, real estate and data centers.

In 2017, Harrison bought the 83,368-acre Cielo Vista Ranch, which was listed for the price of $105 million, property records show. The property includes Culebra Peak and its summit at an elevation of 14,047 feet above sea level. Harrison now charges mountain climbers a fee of $150 for access to the peak. Other peaks on his property exceed 13,000 feet in elevation, according to a website posting by the Mirr Ranch Group, a real estate brokerage.

His takeover and plan for a fence revived a long and thorny saga. Taylor’s restriction of local residents’ access to the land violated terms of an 1863 agreement called the Beaubien Document, which granted rights to “benefits of pastures, water, firewood and timber.”

After the two-decade court battle in the case called Lobato v. Taylor, Colorado’s Supreme Court upheld communal rights. And now residents contend those rights may be violated again as Harrison erects a fence.

‘’I don’t call it a fence. I call it a wall,” Jaquez said. “Why isn’t the state doing something?’’

In a 2018 letter to the Land Rights Council, Harrison dismissed community concerns about access, saying he respects community rights but adding that that some residents were “abusing” their rights.

‘’There is a small group of people who abuse their rights by doing far more than is legally permissible at the ranch,” he wrote. “The easement rights do not include the right to hunt, fish, picnic, or otherwise use the ranch for recreational purposes.’’

The incursions of billionaires above San Luis reflect a quiet and broadening shift in ownership of land around the Sangre de Cristo mountains, located in southern Colorado east of the Rio Grande River. Once controlled by agriculture-oriented communities that relied on access to the land and water to survive, vast tracts now are sought by outsiders for other purposes – such as recreational hunting and preservation as natural open space – adjacent to federally managed forests and wilderness.

Private property can play a key role in conservation of nature, according to Ben Lenth, senior conservation project manager for Colorado Open Lands, a land trust organization that oversees legal conservation easements, in which new owners commit to protecting land and water against future development in return for tax benefits that defray the cost of their purchases.

Photo by Konrad Flæte Gundersen

Colorado Open Lands, based in metro Denver, works in partnership with landowners to ensure protected landscapes stay ecologically healthy. In 2009, 44,000 acres of the Wet Mountain Valley on the east side of the Sangre de Cristos was protected under conservation easements, Lenth said. In 2021, owners continued to place conservation easements on valley terrain and the Colorado Open Lands statewide area protected under easements surpassed 670,000 acres, he said.

These easements reflect changes in ownership in favor of people “trying to protect their place,” he said. Conservation easements long have been used to try to minimize degradation of private property with the goal of limiting human use.

Will low-income and otherwise marginalized communities be displaced?

“We grapple with this,” Lenth said, adding that easements can be designed to guarantee public access. The increase in total acreage protected under easements in the area signals robust real estate commerce. And the new owners include billionaires, who sometimes wield power to exclude others from property.

“That’s where our success lies, in that compromise,’’ Lenth said. Conservation easements aren’t a perfect way to save natural space, he said, but this is better than the alternative of abusive land use and development that degrade unprotected land.

On the west side of the mountains, San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council director Christine Canaly concurred that easements can bring benefits, especially if they are flexible.

“Grazing can be a benefit to the land and the consumer,’’ Canaly said in an interview.

But the massive agricultural sector in the San Luis Valley may not be ecologically sustainable, she said, citing water supply limitations. “There’s a significant acreage of land that needs to go out of production.’’

If that happens, “there’s a great potential for habitat restoration on the valley floor,’’ Canaly said. “What we need to do is un-fragment the landscape.”

In the town of San Luis (population 613), residents said the incursions by new billionaires complicate an already difficult struggle to deal with changing environmental conditions as global warming intensifies. The end result for families who have lived in the area for centuries is increased anxiety about the future.

‘’Without water, you don’t have life,’’ Jaquez said. ‘’Without land, you don’t have peace.’’