The role of the corrections officer (CO) in America’s prison system today is widely misunderstood.[1] Superintendents, inmates, spouses and even the officers themselves often struggle to understand the exact nature of their role in the prison. Conflicting representations of corrections officers in popular culture are partly to blame; as a society, Americans feel grateful to prison staffs for ensuring our safety from convicted felons, yet always hope the prisoner on the page or screen will manage to outsmart the oafish guards keeping watch. As awareness of prison brutality has increased on the aftermath of Ferguson and Baltimore, corrections officers—not police but agents of the state involved, like police, with criminality—are challenged alongside peace officers who work outside the walls. COs are sometimes blamed for high recidivism rates and psychological damage to inmates. Treating corrections officers as scapegoats for the faults of America’s prisons, however, is a misguided approach to the penal system.

A historical survey of early guards and later corrections professionals within Cañon City’s prisons more constructively shows how custodianship of offenders has changed since the nineteenth century. It reveals shifting perspectives on the purpose of prisons in American society and an increasingly complex set of expectations for those who now who must assume the roles of both authoritarian supervisors and gentle reformers. The corrections officer’s contemporary job description contains elements of a simplistic past as well as the idealistic future. In the context of an arrogant penal system unwilling to hold itself accountable for institutional faults, this conflict of ideals makes the corrections officer’s task nearly impossible. To that extent the framing of the corrections officer’s role materially contributes to the continued failure of prisons to rehabilitate, educate, and return offenders successfully to society.

Turnkeys

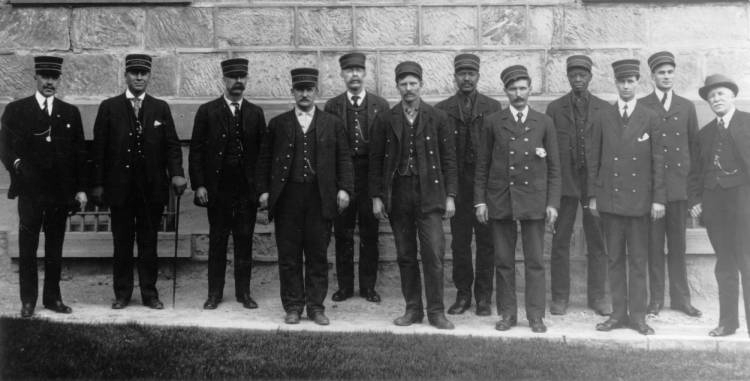

When Cañon City’s first prison was established in 1871, its staff was minimal. The Colorado Territorial Prison employed just one warden and six guards called “turnkeys” because their jobs consisted of little more than locking and unlocking the prisoner’s cells.[2] This position paid $25 per month and required no education or physical competency; most guards were over seventy years old.[3] For many years, these turnkeys took a casual approach to their role, frequently neglecting to wear the proper uniform or maintain a professional appearance.[4] While the informality of Cañon City’s prison employees violates today’s corrections standards, greater regulation would have been superfluous in the 1870s, for the city boasted a meager population of 229 people, among whom convicts outside the walls were well-known and with few resources to escape the community.[5] By the turn of the century, however, Colorado’s population had passed half a million and Cañon City had itself burgeoned, requiring larger prisons and greater responsibility on behalf of the guards.[6]

The expansion of Cañon City’s prisons led to an overall tightening of security mechanisms, for the task of keeping prisoners in and contraband out now required more vigilance than in years past. Similarly, as the inmate population crept higher, industry within the prisons grew more robust, requiring more staff to oversee the production of various goods. While the hiring requirements for prison guards changed little until the 1950s, protocols within the prison grew stricter, allowing guards increased control over the growing number of inmates. Guards escorted prisoners in formation to and from their cells, forcing them to hold their arms across their chests while moving about the facility.[7] Casual conversation between inmates and guards was strongly discouraged; if a prisoner wished to speak with a guard, he was required to remove his hat, cross his arms over his chest, and address the guard by his formal paramilitary rank.[8] Corporal punishment was the favored method of discipline; a 1931 newspaper article describes how one prisoner was whipped in a “spanking machine” after assaulting a guard.[9]

The relationship between prisoners and guards in the early twentieth century was brutal in some ways, yet elements of trust were also ingrained in prison society. Colorado’s penitentiaries were hailed nationally for their implementation of the honor system in prison labor camps, in which several “trusty” inmates would be appointed to supervise industrial operations alongside guards.[10] By the 1920s, this system was recognized by criminologists nationally as a practicable solution to underfunding, as prisons could curb the expense of hiring more guards by using prisoners instead.[11] The honor system was a key feature of industrial enterprises within Cañon City’s prisons for many decades. Unfortunately, an incident in 1976 brought about the swift termination of the practice. A trusty inmate raped and murdered a prison guard’s family while staying at their ranch in a work-release program.[12] Despite the tragic circumstances surrounding the ensuing discontinuation of the honor system, however, its success in Colorado’s prisons in the early 1900s had provided a longstanding pattern of supporting the rehabilitation of prisoners, laying the foundation for future theories regarding reform.

Hiring guards

Scholarly discussion about improving prison guards began to emerge in the 1940s and focused primarily on regulating hiring practices. Criminologists suggested implementing salaries instead of hourly wage plans to encourage productivity and attract qualified candidates. They recommended emphasis on the rehabilitative nature of corrections in hiring literature in order to have a more social service-minded applicant pool.[13] Within the Colorado State Penitentiary, the appointment of Harry Tinsley as warden in 1952 triggered a profound change in the prison’s atmosphere, as the new warden sought to convert the prison into a place where convicts could be reformed, educated, and enabled to lead useful lives after their release.[14] American society more widely began to hold a more forgiving view of prisoners. Guards, now frequently called corrections officers, were increasingly taught to treat inmates with respect, and to shy away from the use of force unless absolutely necessary.[15] In his seminal 1958 analysis of prison culture, The Society of Captives, Gresham Sykes notes that guards in a New Jersey penitentiary in this decade were instructed to strike prisoners only with nightsticks as opposed to their bare hands, the rationale being that threat of higher staked violence would encourage inmates and guards alike to seek alternative methods of confrontation.[16] Increasingly nuanced training for corrections officers, emphasis on rehabilitative role, and new respect for inmate rights all contributed to a greater movement to professionalize the corrections career that would soon take hold of Cañon City’s prisons.

The 1970s again saw large-scale reforms in Cañon’s correctional policies, significantly altering the role of officers within the prison society. COs were now required to have at least a high school diploma, although a greater number entered the position with a college degree.[17] The basic training curriculum for corrections officers began to include lectures on human behavior and leadership.[18] Colorado prisons abandoned military-style ranks for officers, replacing them with a five-tier career progression to allow for upward mobility without fundamentally aggressive connotations.[19] The adoption of a more corporate structure for prison administration further influenced the ways in which corrections officers interacted with both inmates and their superiors. While in the old days the warden had the final, unquestionable word in every matter, now the superintendent’s decisions might be appealed.[20] As new agency was bestowed upon both inmates and corrections officers, legal liability within the prison system became an increasing concern as corrections employees could now be more easily held accountable for misconduct. Between 1979 and 1985, the number of lawsuits on behalf of inmates doubled nationally.[21] Previously, very few stories of corrections officers abusing their authority ever reached Cañon City’s local news media. With all of these lawsuits have come newspaper articles raising public scrutiny of corrections employees and their conduct.

As Civil Rights agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission started to shape the hiring practices of private and public enterprises across the nation after the 1960s, the demographics of corrections officers shifted. More women and minorities found work as correctional officers in prisons, creating diversity in a profession traditionally dominated by white males. In 1987, women comprised about forty percent of the graduating class at the Criminal Justice Academy at Pueblo Community College.[22] According to corrections staff in Cañon City, the increasing presence of female corrections officers has had profound effects on prison culture, as inmates are less inclined to commit violence against women officers due to preconceived notions of female physical weakness.[23] Females working alongside males have challenged the cultural machismo common among corrections officers, creating complexities in the social dynamics of prisons.

As the profile and role of corrections officers have changed over the course of the last century, changing ideas about the purpose of prisons have also shaped policies on a local and national level. Although the penal system’s moves toward reform, rehabilitation, and education are founded in good intentions, new policies have not always effected positive change due to institutional constraints such as underfunding and overcrowding. Prison staffs do not always have adequate resources to carry out noble enterprises such as education. Yet a fair share of the blame can be placed upon the corrections officers tasked with carrying out reformative policies, though not through a fault of their own. The breadth of responsibilities placed on contemporary corrections officers is so massive that success is nearly impossible.

Responsibilities of corrections officers

Not only are corrections officers expected to counsel inmates and educate them in skills so that they may find work after leaving prison, but these same individuals must also perform the traditional role of controlling inmates’ behavior and preventing their potential harm to those outside the walls. Officers need to maintain constant vigilance in order to prevent fights and escape attempts, and must resist being manipulated into bending the rules for crafty inmates. Corrections workers are thus unable to allow the trust and personal connection necessary for rehabilitative programs to work. Paralyzed by rules, regulations, and the need to project authority over inmates, COs often fall short in the task of imparting meaningful knowledge and wisdom upon the prisoners. Even employees who are not expected to fill the security role have difficulty connecting with the inmates. “Be friendly, but don’t be friends,” says Dennis Babcock, chef and educator in a Cañon City prison. “They play games, try to get you to do favors for them. Something small today can be something big tomorrow.”[24] While the role of the corrections officer is thus more dynamic and influential than it was in decades past, added responsibilities have proven to be a burden on corrections employees, often resulting in frustration and disappointment.

Examining the ways in which corrections officers have changed since the beginning of Cañon City’s prisons brings attention to how many things have stayed the same. Most impediments to the success of recent reforms in prisons are institutional, path-dependent features integral to the penal system as it has been historically constructed. For example, racial inequality among inmates and corrections officers has been a factor in Colorado’s prisons for over a century. In 1891, blacks made up twenty percent of the national inmate population but only twelve percent of the general population.[25] Meanwhile, every single employee in Colorado Territorial Prison was a white male. Today, Latinos and blacks constitute fifty percent of Colorado’s prison population, but only twenty-three percent of the Department of Corrections staff are persons of color.[26] Since most of Colorado’s prisons were established in areas of low population density such as Cañon City or Limon, the people hired to work there are not only predominantly white but usually have had little contact with people of color outside of the prisons. This relative inexperience can lead corrections officers to have negative perceptions of minorities.[27] Such disparities affect not only inmates of color but Hispanic and African American corrections officers, who are sometimes subject to discrimination or even targeted by racist inmates. Instances of such tensions can be dated back to the Territorial Prison Riot of 1929, when Jim Pate, a black guard, became a special target of rioting convicts because he had foiled several previous attempts at escape.[28] More recently, a group of corrections employees sued the Colorado Department of Corrections on the grounds that its hiring and promotion practices discriminated against blacks. The group of six employees also testified that white corrections officers had been known to address inmates with racial slurs with no repercussions.[29] Although the diversity of corrections officers is steadily growing, it has not kept in pace with the increasing racialization of the inmate population. Racial tensions continue to roil Colorado prisons and incarceration facilities elsewhere.

Prison rules: formal and informal

In-prison social interactions governed by countless rules for inmate behavior inevitably shape a penal system, and variations of such tools of social control have defined prisons in America for decades. While the implementation of prison rules is considered a necessary measure for preventing outbreaks of violence or escape attempts, the consequent loss of trust for and from inmates increases hostility within prisons, sometimes driving offenders to break the rules. As Sykes explains, while every seemingly arbitrary regulation may have some valid explanation behind it, corrections officers often do not provide a rationale, hence arousing resentment. Sykes reasons that inmates are kept in the dark about certain rules because if they are told the purpose of a specific regulation, they might then assume that they have the right to know, and thus the right to rebel if they disagree with a rule’s intent.[30] Sykes’ account may seem less acceptable today, when understanding of inmate rights and legal liability seems instead to constructively shape correctional officers’ conduct, but the lack of communication between inmates and prison staff can still have dire consequences for inmate-corrections officer relations.

An “us vs. them” mentality pervasive in American prisons has proven to be a significant roadblock in efforts towards reform, as mutual distrust at all levels of a prison society stymies rehabilitation efforts by breeding conflict. For many years, convicts have adhered to a “prison code” first recognized in academic criminology in Sykes’ path- breaking account. The principal rule in this pattern of inmate behavior is to associate with guards as little as possible.[31] Inmates who align too closely with corrections officers usually lose respect of other prisoners, even if their intentions are benign. A resulting inclination to resist connections to corrections officers then undermines COs’ attempts to counsel or educate inmates. Similarly, officers who are too keen to prevent crime or break up potential gangs may see their efforts backfire, for cracking down on inmates tends to alienate them, driving them towards criminal activity or gang affiliations.[32] Resentment towards corrections officers is pervasive even among inmates who do not engage in subversive behavior. Many feel that administrative efforts to professionalize the prison system by hiring more educated staffs have failed. A letter written by an inmate and published in the Denver Post in 1998 illustrates this attitude. Aristedes Zavaras, an inmate serving a life sentence since 1988, there berates corrections workers as “minimally literate, culturally unsophisticated, and [lacking] a normal adult level of logic or reasoning skills.”[33] Furthermore, some inmates believe the change in terminology from “prison guard” to “corrections officer” does not actually reflect change in the goals of prison staff.[34] Failure to follow up high-minded principles of reform with concrete actions has undercut the legitimacy of corrections officers in the eyes of many offenders, who see administrative changes in policy as little more than empty promises.

Inmates are not alone in bearing grievances against their custodians as their effective superiors. As corrections officers’ list of responsibilities grows, they too may feel frustration towards prison administrators. In extreme cases, these feelings can drive officers to engage in criminal activities with inmates. Cañon City corrections officers have been charged with providing cell phones, drugs, and other contraband to inmates in recent decades.[35] Although rare, these instances can lead upper-level corrections employees to distrust front-line corrections officers. Meanwhile, just as rules are not always explained to inmates, COs do not always receive clear instructions from prison boards and thus often fail to carry out programs effectively.[36] A culture of mistrust has not only impeded the success of support programs for inmates but for corrections officers as well. Desert Waters Correctional Outreach, a mental health counseling program in Florence, reported that it had difficulty earning the endorsement of prison officials because administrators were suspicious that it was a scheme devised to spy on their work.[37] While counseling programs for corrections officers certainly provide channels for guards to speak freely about the stresses of work, confidentiality decrees such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) both prevent vital information about the prison system from falling into the wrong hands and limit COs’ voice. The atmosphere of mistrust permeating the prisons of Cañon City serves to alienate each group from the others, causing reform efforts to fall short in abolishing the inefficiencies and injustices that have plagued the system since its birth.

Looking at corrections from a new perspective

Ordinary COs’ personal narratives of the prison experience are rarely offered for public consumption; this is no surprise because these men and women lack both the clout of the bureaucratic administrators and the romantic appeal of the inmate. Portrayals of corrections officers in popular culture, including those of Orange is the New Black and The Shawshank Redemption, tend to paint prison staff as cruel tyrants bent on making inmates miserable. Even the old film Cañon City, which depicts the 1947 prison break at Colorado State Penitentiary and was completely endorsed by prison officials, ignores the perspective of the guards, opting to romanticize the inmates instead.[38] Nonetheless, prison reform in the age of mass incarceration requires understanding of the perspective of the corrections officer within the prison’s societal structure, for these men and women not only have greater contact with inmates than any other group engaged in judicial or rehabilitative work, but with the greater public through networks of family and friends. The history of corrections officers in Cañon City is framed by their geographical region, but the experiences of these men and women can be generalized to the greater American prison system, especially with the support of prison literature and studies from across the country.

If American prisons are to ever achieve their goal to serve as rehabilitative institutions constructively influencing the lives of those incarcerated within them, the system must be reimagined such that corrections officers can successfully embody the role of counselors and educators. A greater degree of trust must be vested in both prison staff and inmates in order to allow them to feel empowered to pursue personal growth. The ethos behind “innocent until proven guilty” expressed in free society should be established behind bars as well, prompting corrections officers to focus less on punishing prisoners for their mistakes and more on celebrating their efforts towards productivity and recovery. Prioritizing the prevention of crime and escape in America’s prisons has caused rehabilitative initiatives to fall by the wayside, in large part due to the overblown responsibilities it lays upon corrections officers. While decades may pass before the ideal vision of this nation’s prison system merges with reality, a comprehensive revision of the expectations for corrections officers in the meantime will allow these people to approach their job differently, paving the way for lasting, positive change.

[1] Originally researched and drafted by Madeleine Engel.

[2] State of Colorado, Department of Corrections, History and Mission Statements, June 13, 1986, 3.

[3] Victoria R. Newman, Prisons of Cañon City (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 41.

[4] “Prison Guards Must Keep Up Neat Appearance,” unattributed fragment, September 16, 1931, Royal Gorge Regional Museum (hereafter RGRM) “Articles Relating to the Prison” file.

[5] United States Census Bureau, “1870 Decennial Census of Population and Housing,” 95, accessed November 9, 2015, http://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html.

[6] United States Census Bureau, “Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives,” accessed November 6, 2015, https://www.census.gov/dmd/www/resapport/states/colorado.pdf.

[7] Newman, 35.

[8] John Lemons, “DOC Facilities, Staff Reflect Change in American Society,” Cañon City Daily Record, May 11, 1987.

[9] “Convict is Murdered at State Prison This Morning,” unattributed fragment, November 21, 1931, RGRM “Articles Relating to the Prison” file.

[10] W. E. Collett, “Where Prisoners Are Trusted,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 3 (1912): 43, accessed November 4, 2015, doi:10.2307/1132844.

[11] Bryant Smith, “Efficiency vs. Reform in Prison Administration,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 11 (1921): 588.

[12] “Prison Guard, Family Killed,” Ellensburg Daily Record, August 28, 1976.

[13] D. E. Lundberg, “Methods of Selecting Prison Personnel,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 38 (1947): 16.

[14] Willard Haselbush, Denver Post, undated fragment, RGRM “Articles Relating to the Prison” file.

[15] Lemons, “DOC Facilities.”

[16] Gresham M. Sykes, The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1958), 49.

[17] Lemons, “DOC Facilities.”

[18] David Duffee, “Correctional Officer Subculture and Organizational Change,” Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency 11(1974), 168.

[19] Robert William Baker, “The Effect of Educational Attainment on the Job Satisfaction Level of Correctional Officers,” M.A. thesis, Washington State University, 1979: 20.

[20] Lemons, “DOC Facilities.”

[21] Don Josi and Dale K. Sechrest, The Changing Career of the Correctional Officer: Policy Implications for the 21st Century (Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998), 80.

[22] Nanette Brazell, “Women in Corrections,” Cañon City Daily Record, September 5, 1987.

[23] Ada Brownell, “Corrections Careers Luring More Women,” Pueblo Chieftain, March 14, 1989.

[24] Lydia Reynolds, “Babcock Loves Spending All Day in the Kitchen,” Cañon City Daily Record, June 1, 2001.

[25] Roland P. Falkner, “Criminal Statistics,” Publications of the American Statistical Association 2 (1891): 381.

[26] Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, “2010 Colorado Quick Facts,” accessed November 4, 2015, http://www.ccjrc.org/pdf/2010_Colorado_Quick_Facts.pdf.

[27] Robert Koehler, “The Organizational Structure and Function of La Nuestra Familia within Colorado State Correctional Facilities,” Deviant Behavior 21 (2000): 156.

[28] Unattributed fragment, Cañon City Daily Record, October 10, 1929, RGRM “Prison Staff” folder.

[29] Jeffrey A. Roberts, “Prison Employees Sue State,” Denver Post, March 13, 1993.

[30] Sykes, 75.

[31] Koehler, 159.

[32] Ibid., 176.

[33] Lori Lynn McLuckie, “Corrections Workers Fail to Live up to Glorified Billing, Inmate Says,” Denver Post, November 1, 1998.

[34] Koehler, 166.

[35] John Lemons, “Former Corrections Officer Facing Criminal Charges,” Cañon City Daily Record, January 16, 1998.

[36] Duffee, 159.

[37] Paul J. Goetz, “Stress Behind the Razor Wire,” Canyon Current, December 16, 2005.

[38] Cañon City, dir. Crane Wilbur (MGM, 1948), DVD (Bryan Foy Productions, 2010).