From the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the Boston Marathon bombing—from the mass shootings at Columbine to those in Orlando—programmed and on-demand news feeds have demonstrated how fear induced by senseless crimes engulfs the psyche of an entire nation.[1] The twenty-four-seven news cycle feeds a nearly insatiable American hunger for stories of lawbreakers victimizing society. In this climate, the “criminal”—an identity rendered over centuries, drawing from tales of infamous outlaws sensationalized by the media to television dramas touting the law and its enforcers—commands a newly prominent position in the American consciousness. Issues of culpability trouble the public conscience. Who warrants the blame?

While crime and social deviance have persisted since America’s founding, norms for punishment and treatment of criminals have varied over time. The early nineteenth-century transition from capital or corporal punishment to long-term bodily confinement represented a shift in criminal justice ideology that prison theory construed as progress.[2] As the contemporary American carceral system undergoes increased public scrutiny, however, incarceration—a method once lauded for its humanity, particularly in a country founded upon the ideals of freedom, democracy, and individual liberty—is forcefully interrogated. Is the U.S. prison system as fair as it claims? Is it salvageable? If so, what role does the public play in impelling systemic change? Historical analysis grounded in knowledge of modern debates around penal institutions provides a useful line of inquiry into how the American justice system became freighted with injustice.

From the outside, the most prominent and symbolic feature of modern prisons is the wall, serving as the dividing line between “bad” and “good” elements of society. Sociologist Gresham Sykes, in his seminal 1950s study of a New Jersey maximum-security facility, noted that “[t]he prison wall does more than help prevent escape; it also hides the prisoners from society. If the inmate population is shut in, the free community is shut out.”[3] Cañon City, Colorado, a community with many such isolating walls, represents a unique instance of a free society’s interaction with its incarcerated remnants. Home to seven state facilities and neighbor to four federal penitentiaries in nearby Florence, Cañon City has long served as the incarceration destination for convicts living out sentences severing them from society and its freedoms. In Cañon City and Florence together, inmates constitute thirty-eight percent of the combined population.[4] The corrections industry provides over half of the county’s jobs, so that most families depend on the prison population for their income.[5] Persons directly or indirectly involved in corrections inevitably look at the prisoner from a different vantage point than those connected with incarcerated offenders. A hierarchy of power divides custodians and captives, extending into the social fabric in the Colorado town where these facilities stand.

The nearly 9,000 inmates concentrated in this sprawling region of Colorado are only a small proportion of the two million Americans behind bars, but collectively and as individuals they represent American criminality. The South African activist Nelson Mandela, twenty-seven years a prisoner and an important voice in international discourse of incarceration as well as the battle against apartheid, argued that all civically engaged individuals should care about the current and past state of prison life: “a nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.”[6] Public discourse in the United States, however, has generally shied away from how we view and treat prisoners. Early twentieth-century political prisoner Kate Richards O’Hare wrote in her memoir of incarceration In Prison, anticipating Mandela’s perspective, “We who lived in prison…know that our prison system is the true reflection of our national life, our national ethics, our national morals, and our national sense of justice.”[7] Consideration of the prisoner’s role in our past, present, and future poses the following question: what does it mean to deem someone “criminal?”

Defining the criminal

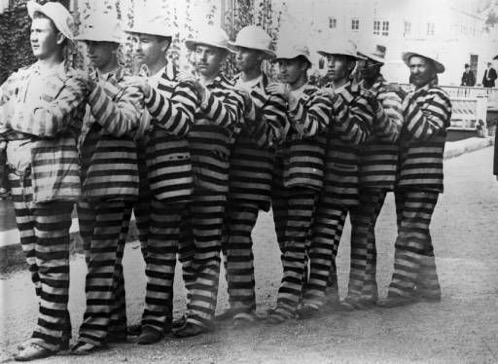

A criminal is a person legally convicted of violating the laws of the society in which he or she lives. Unsurprisingly, laws written by those in control to preserve their power and property are enforced primarily against the powerless and unrepresented. Once convicted in a system privileging elites, the criminal’s “rap sheet” becomes an indelible record—sometimes his or her identity for life. Who is convicted, how the structure and processes of the legal system lead to disproportionate conviction of certain social groups—these are important questions of social justice. In the American ideal, every individual is presumed innocent until proven guilty, entitled to equal legal defense and judgment under the law. In practice, however, not everyone benefits equally from Constitutional protections. The American public generally assumes that those finding themselves in state and federal prisons have had access to legal representation, but concepts of the adequacy of such representation vary over time and jurisdiction. Inadequate or overburdened legal representation (a public defender, often underpaid, may have a portfolio containing hundreds of cases) leaves most offenders with prison sentences resulting from plea bargains – no jury of one’s peers involved.[8] Prisons and jails become long-term holding cells for the population’s most vulnerable cast-offs.

The widely accepted notion of “minority rights” is a contradiction in terms in the American penal system. People of color, immigrants, people without money or property, and the mentally ill—the minorities, the dispossessed, society’s “others”—are groups historically ostracized within the criminal justice system. Legal marginalization often stems from limited access to Sixth Amendment tools guaranteeing judicial fairness.[9] Conversely, certain people appear cloaked in privilege, evading long term retention behind bars as their social standing, connection, or power exonerates them or reduces their sentence. Take the case of Brock Turner, a white male Stanford University swimmer accused of sexually assaulting an unconscious woman behind a dumpster in California in January 2015.[10] Although caught in the act and found guilty of three felony counts, the law determines that Turner will never see the inside of a prison as punishment for his crime. The judge presiding over the case decided six months in county jail (of which Turner will likely only serve half due to California felony sentencing laws) was more appropriate than the six-year minimum because “a prison sentence would have a severe impact on him.”[11] Juxtapose Turner’s sentencing to the case of Brian Banks, also a promising athlete in California. Accused of rape in 2002 at age sixteen and tried as an adult, he faced forty-one years to life in prison.[12] Banks, a black man, plead no contest to avoid an all-white jury. Though later evidence confirmed his innocence, Banks spent five years in prison on trumped-up charges.[13] The judge, in Banks’s case, did not consider the “severe impact” on Banks as a person. A comparison of the treatment of these two individuals caught up in the justice system suggests not that more time in prison would “fix” Turner or make up for his misdeeds, but illustrates a stark polarity representing imbalance and injustice in American jurisprudence. Courts sentence people convicted of very similar crimes, even in the same state, entirely differently. The justice system continually positions those of certain class and color as perpetual outliers. Yet it is easy to blame systems without looking at the underlying people who support and sustain them. Surely it is not just judges making these mistakes where lives and futures are at stake.

The example of rape sentences in California speaks to racial bias; legal scholars, noticing the seriousness of this phenomenon, have delved deeper into its national prevalence and cultural, social, and economic sources. Michelle Alexander systematically investigated racial bias in the justice system in her path breaking, mightily influential 2012 study The New Jim Crow, observing that “for nearly three decades, news stories regarding virtually all street crime have disproportionately featured African American offenders.”[14] Lisa Bloom expanded on Alexander’s assertion two years later in her book Suspicion Nation, noting “the standard assumption that criminals are black and blacks are criminals is so prevalent that in one study, sixty percent of viewers who viewed a crime story with no picture of the perpetrator falsely recalled seeing one, and of those, seventy percent believed he was African-American.”[15] These grim statistics demonstrate that when it comes to identifying a face of a different race, more mistakes and, hence, wrongful convictions are likely to occur. The Innocence Project, a non-profit legal organization committed to identifying and exonerating those wrongfully convicted, found that fifty-three percent of misidentification cases where the race is known involved cross-racial identification.[16] Although the American criminal justice system theoretically operates on the principle that every accused is innocent until proven guilty, certain identity characteristics feed collective pre-judgment, leaving some individuals more vulnerable from the witness stand. Past frames present. To this day, historically marginalized communities pay the greatest price for crime.

Prison riots and the public

Once behind bars, offenders face a continuum of similarly racialized injustice. Their connection to the outside world is confined to letters, proctored visitation, and the occasional fee-based, monitored telephone call. This access, at the discretion of the penal institution, is subject to compliance with policies of “good behavior.” As Sykes points out in the 1950s and as still maintains sixty years later, “at certain times, as in the case of riots, the inmates can capture the attention of the public; and indeed disturbances within the walls must often be viewed as highly dramatic efforts to communicate with the outside world.”[17] An instance of such performative engagement of public attention emerged in the December 30, 1947, riot at Colorado State Penitentiary. While the riot itself provides an intriguing line of inquiry, an analysis of the public response and rationalization following the event is still more instructive. As the news wires chronicling the characters, the motives, and the gritty details, Hollywood capitalized on this opportunity to dominate the public imagination with a “morality play” of a story depicting good versus evil.

Just six months after the riot, directors and film crews flocked to Cañon City, creating a movie covering the events of the turbulent December day. This movie, titled Cañon City, speaks to a public yearning to create narratives around the incarcerated.[18] While the viewer is introduced to all twelve escapees, special attention is given to James Sherbondy, a convict who hesitated to join in the riot, and who is treated in the film with much historical accuracy. Upon his escape, Sherbondy entered a local family’s home, taking them hostage. When a child of the house suddenly fell ill, Sherbondy allowed the seven-year-old boy to be taken to the hospital. This compassionate act, as represented in the movie, arouses the viewer’s sympathy, serving as a reminder that not all human decency is lost in prison. In the film as in the event, Sherbondy was recaptured the next day and severely punished for the escape attempt. Playing himself in the film, Warden Roy Best then shamelessly self-promoted his regime of strict discipline and unquestioned submission to authority by those paying their debt to society—as indeed he did in the historical instance.

Two years after the movie’s release, ironically, Best was charged by a Colorado grand jury with five counts of embezzling state property. The town rallied behind Best, gathering the funds for his $10,000 bond.[19] Even as the warden faced a two-year suspension, his notoriety increased. Details of his abuses became public knowledge. Nonetheless, when most of the relevant evidence was destroyed prior to the trial, Best was acquitted. Although it is unclear how Best’s trial was rigged, public influence was evident. The people of Colorado had trouble accepting the idea that their flagship prison’s esteemed warden was a criminal like those he watched over and punished. As someone appointed by and reaffirming Colorado political power, Best did not fit the image of the criminal purported by the media. In contemporary experimental psychology, this pattern is called confirmation bias.[20] This principle similarly explains how it can be easier to accept that someone living in poverty is inclined to break the law, and thus to justify locking any in that segment of society behind bars, than that a middle-class perpetrator is guilty and justly subject to confinement. The human predisposition to affirm or exaggerate pre-existing impressions has ensured the longevity of prisons, as most of the families with members who are incarcerated lack the resources to challenge the system and the narrative of criminality as applied to them. Best, however, had the resources and the public’s support, and thus escaped the legal label of criminal. Three days prior to his reinstatement as the warden of the Colorado State Penitentiary, Best suddenly died. Thereafter the Colorado prison system entered a new era of reform under the leadership of Harry Tinsley.

Prison as Continuum: Re-“carcerating” the Incarcerated

Tinsley, believing that his duty as warden extended beyond discipline, helped institute more than twelve self-help programs at CSP. “Society can’t gain by merely caging its offenders behind bars,” Tinsley asserted in an August 1968 Denver Post article. His policies reflected this ethos, attempting to create a sense of community in prisons to better prepare the inmates for responsible places in the world outside. Tinsley established a dialogue and a sustained relationship between the prisoners and the free population with programs like “Don’t Follow Me,” in which convicts traveled outside the prison walls to talk to teenagers and adults about their life in prison and what brought them there. A veteran guard commented, “Roy Best would spin in his grave if he knew a bunch of cons were running around the countryside giving talks on behavior.”[21] Paradigms that placed little to no value on the life of a prisoner were changing under Harry Tinsley’s administration.

Colorado’s first parole preparation facility opened in 1959 under Tinsley’s leadership. Edward W. Groul, executive director of the state’s adult parole division at the time, described the center as a place where prisoners “learn to bridge the gap between prison and free society.”[22] The institution of this Pre-Parole Release Center acknowledged and responded to the difficulty inmates face upon their release and re-entry into society. The center continues to charge the corrections system with more than just confining and warehousing those who have erred. As Tinsley made clear, “Locking them up is not enough. We have to do something to help them help themselves and become useful citizens.”[23] Such an idea was radical because it looked past the isolation of inmates from the outside world and towards their reintegration into the society from which they had been forcefully removed. The funding of Lyndon B. Johnson’s mid-1960s Great Society-era programs had projected the image that prisons and inmates were worthy of these government investments, but involvement in the Vietnam War put prisoners’ issues on the backburner, retarding further such development.

When the Vietnam War ended, concern for the growing criminal population appeared stunted. Instead, on a national level, public punitiveness seemed to be increasing in the 1970s.[24] In 1974, chief guard training officer of Colorado State Penitentiary Uhland blamed the abuses of power occurring in Colorado prisons over the last century on the public’s neglect of the incarcerated population, stating that “Public apathy to what goes on inside prison walls anytime but during a crisis allows the problems to perpetuate themselves. Do you know why almost all prisons have high walls around them?” Uhland continued, “A tall chain link fence would accomplish the same purpose. People don’t want to see what goes on inside a prison. They don’t want to know.”[25] Most operate on an “out of sight, out of mind” basis in regard to the prisoner. Corrections Director Rudy Sanfilippo echoed this sentiment a year later in a Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph article, blaming the public’s attitude on “witches syndrome:”

A century ago the sanctimonious of Salem burned the mentally ill as witches. Lepers were isolated for fear that you could contact the disease by looking at a leper…there was a feeling that if you could toss the offensive of the world into a snake pit you would have them out of sight and out of mind. People are at the same level of thinking right now regarding criminal offenders.[26]

In 1975, Sanfilippo tried bringing the problem into a larger context by reminding people that life on the inside influences life on the outside. “What we do now is brutalize offenders,” he opined, “so how come anybody should be surprised if when they get out of jail they hold up the nearest store? They come out mad and vengeful.”[27] Indeed, recidivism metrics are held up by detractors of rehabilitation as support for their work. Colorado had the third-highest return-to-prison rate in the nation in 2010, 52.4 percent according to a report by the U.S. Department of Justice.[28] While the 2013 recidivism rate cited by current director Rick Raemisch is forty-nine percent (a three percent decrease), this rate still does not reflect well on the success of the Colorado prison system.[29]

Recidivism rates all too easily confirm existing biases that the root cause of criminal behavior is a failure of individual character, not of wider society. In this view, some people are inherently criminal—when given the choice between freedom and crime, they choose crime. To attempt to rehabilitate offenders is, according to this logic, to throw good money after bad. Such conclusions are reached without full knowledge of the reality offenders face upon release. Hiring practices even for unskilled jobs discriminate against persons with criminal records. Mental health and medical support, as well as public housing, are difficult to find. Competition for work is harsh when one’s skills are stale and outmoded. Municipal restrictions, including parole and fines, further limit job flexibility. The prisoner returns to society stigmatized, disenfranchised, and consigned to minimum wage jobs, constant parole surveillance, web mugshot postings, and routine searches in DNA crime databases. The formerly incarcerated individual, in effect, carries a life sentence. The struggle to re-claim a sense of dignity becomes constant. Unwanted and rejected by mainstream society, some former inmates simply cannot re-envision their place in it. Another wall, built on shame, ostracism, fear and social contempt, keeps them prisoners long after their “debt to society” is repaid.

Looking forward

While progress in viewing the prisoner as a fellow human being occasionally emerges, public commitment to successful reentry varies over time, sometimes because of events of regional significance. The most recent large-scale setback to the Colorado Corrections Department was the murder of Tom Clements, former executive director of Colorado Prisons. Clements was fatally shot on his front doorstep on March 19, 2013, by Evan Ebel, a recently-release inmate. A tape-recording made by Ebel two days before showing up at Clements’ doorstep suggested that the killing was motivated by anger towards a system wielding a profound, non-negotiable abuse of power—holding him in long-term solitary confinement up until his release.[30] Ironically, Clements was a reformist penologist, making great strides towards decreasing the use of solitary confinement on mentally ill inmates, and Ebel was turned loose prematurely because of administrative error. What happened between them was a tragedy, one that will continue to plague the conscience of Colorado residents and the corrections community alike. The media attention surrounding Ebel in the aftermath induced fear in a public already hesitant to reintegrate ex-offenders into society. The event served as disturbing evidence of what can result when we return people to our states and towns and neighborhoods after degrading their mental and physical faculties, flouting institutional power over individual powerlessness.

Of the 2.2 million persons currently incarcerated in the United States, the vast majority will be released for re-entry. Some estimates hold that ninety-eight percent of offenders will be returned to our communities and neighborhoods.[31] Given that more than twelve million people in the U.S. today have prior felony convictions, few neighborhoods are excluded. Each month, Colorado releases over 800 prisoners on parole or sentence discharge.[32] These individuals return to families and children and a society that tries to erase their existence. In the era of mass incarceration, Americans can no longer afford to ignore those segments of its population enmeshed in the gears of the justice system. Biases aside, we need to reconsider not just when to release our prisoners, but how we intend to include them in the national discourse of how to salvage our justice system. In the future of corrections, adherence to methods and attitudes of the past will no longer do America justice.

[1] Originally researched and drafted by Caleigh Cassidy.

[2] David J. Rothman, “Perfecting the Prison,” in The Oxford History of Prisons: The Practice of Punishment in Western Society, ed. Norval Morris and David J. Rothman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 103.

[3] Gresham Sykes, Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 8.

[4] John M. Glionna, “In Colorado’s Prison Valley, Corrections Are a Way of Life,” Los Angeles Times, August 15, 2015.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1995), 201.

[7] Kate Richards O’Hare, In Prison (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923; repr. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977), 16.

[8] Gary Fields and John R. Emshwiller, “Federal Guilty Pleas Soar as Bargains Trump Trials,” The Wall Street Journal, September 23, 2012.

[9] “The Constitution of the United States,” Amendment 6.

[10] Gabrielle Paiella, “Why Brock Turner Only Got 6 Months in Jail for Sexually Assaulting an Unconscious Woman,” New York Magazine, June 7, 2016, http://nymag.com/thecut/2016/06/why-brock-turner-got-six-months.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ashley Powers, “A 10-Year Nightmare Over Rape Conviction is Over,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 2012.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010), 103.

[15] Charles M. Blow, “Crime, Bias, and Statistics,” New York Times, September 7, 2014.

[16] Sue Russell, “Why Police Lineups Can’t Be Trusted,” Pacific Standard, September 29, 2012.

[17] Sykes, 8.

[18] Cañon City, dir. Crane Wilbur (MGM, 1948), DVD (Bryan Foy Productions, 2010).

[19] Dee Kirby, “Warden Roy Best of Canon City,” Palmer Lake Historical Society 5 (2010): 1.

[20] Paul C. Giannelli, “Confirmation Bias,” Criminal Justice, 22 (2007): 60.

[21] Fred Baker, “Life Doesn’t End in Prison,” Denver Post, August 13, 1968.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Peter K. Enns, Incarceration Nation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 25.

[25] Jay Whearley, “Tensions Build Up Behind Old Walls,” Denver Post, September 22, 1974.

[26] Ray Broussard, “100 Years Behind, Says of State Prison,” Gazette Telegraph, August 6, 1975.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Jennifer Brown, “Parole to Jail,” Denver Post, June 2, 2013.

[29] Kirk Mitchell, “Colorado Prison Population Is Spiking amid High Recidivism Rate,” Denver Post, December 17, 2014.

[30] Alan Prendergast, “After the murder of Tom Clements, can Colorado’s prison system rehabilitate itself?” Westword, August 21, 2014.

[31] Joan Petersilia, “Parole and Prisoner Reentry in the United States,” Prisons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 512.

[32] Prendergast.