Rehabilitation takes many forms, including education.[1] The twentieth century saw the growth of educational opportunities inside Colorado prisons. Cañon City is home to seven state prison facilities, while neighboring Florence houses four federal facilities. Each prison has developed its own education programs at different rates. According to Wayne Patterson, warden of the Colorado State Penitentiary during the 1960s, “there are two important elements in any correction program. . . .education in its broadest sense, and useful productive labor.”[2] If education is such an important element in a correctional facility, have appropriate programs been offered to inmates? How have educational programs within the prisons changed over time? Newspaper articles found in Cañon City’s Royal Gorge Regional Museum archive show the evolution of educational programs offered within the federal and state-run prisons of Colorado. These facilities provide educational programs in the hope that inmates will be better prepared for life after prison if they have an education comparable to individuals outside the walls. Offenders have frequently dropped out of school at young ages in order to help provide for families struggling with poverty or because they have mental disabilities. Educating them while they are serving time in prison is important because educated people have more job opportunities. Prisons provide education in order to help give inmates a foundation for a new life in which they are not compelled by economic circumstances to revert to crime.

Levels of education offered to inmates expanded during the twentieth century. Night schools offered by chaplains gave way, in mid-century, to formal state-supported programs. The Colorado State Penitentiary opened its first official school in 1955 to teach illiterate inmates how to read and write. The first class consisted of twenty-four inmates, fifteen of whom received eighth-grade diplomas. Ira Sanger taught this first class and worked to expand the new program. He was then hired by Warden Harry Tinsley to head an education program for the prison. The program began with only primary and lower secondary school classes. Four teachers taught grades one through eight. Sanger hoped to add high school level classes to the program, but did not have enough outside teachers to accommodate the student inmates.[3] Therefore, he looked for inmates who would be able to teach classes themselves. Sanger eventually found eleven inmates who became self-taught teachers of such subjects as English, math and typing.[4]

Introduction of GEDs and college credit

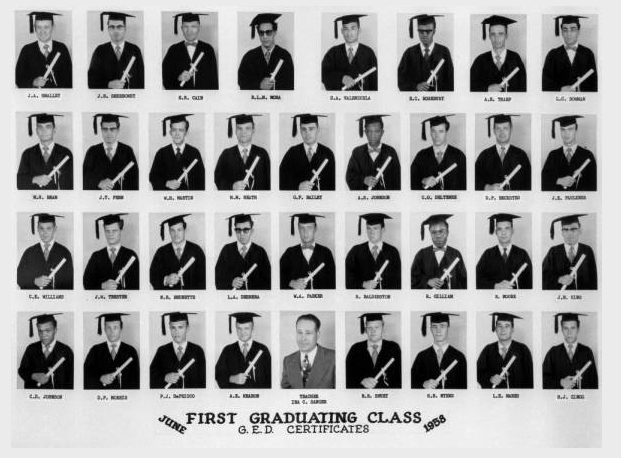

In 1958, the state allowed inmates to receive high school diplomas after completing General Educational Development courses. The eleven inmate teachers then took over teaching courses from a first-grade through twelfth-grade level. All classes were taught in the evenings because the inmates were required to complete their daily work before attending class. The inmate teachers protested the timing of classes because in the evenings they had to compete with television programs for attendance. Many more inmates were enrolled in classes than actually attended. The prison compromised by allowing some classes to be taught during the day, leading to substantial student success. Eight years after the integration of high school courses into the prison education program, over 1,500 inmates had received high school diplomas. Considering that the average grade placement for new inmates who were given the California Achievement Test upon entering the prison was sixth grade, Sanger’s work was had been a considerable accomplishment.[5]

Another significant achievement came in 1967, when after ten years of negotiations the State Penitentiary was able to set up an affiliation with local community colleges to offer select courses at the prison.[6] Southern Colorado State College in Pueblo sent an instructor to the penitentiary every Monday night to teach sociology and every Tuesday night to teach English.[7] An instructor from Adams State taught math and astronomy.[8] The penitentiary paid the colleges for the service and then the inmates reimbursed the state through their work in the prison factory.[9] Sixty-three inmates enrolled in the first quarter of classes.[10] Instructors noted how alert and motivated the inmates were. One instructor claimed his class of inmates was better read than his average freshman class at the community college. Overall, the first quarter of college classes taught at the prison was a success, although they proved expensive for inmates.[11] An inmate needed to work for three months at top prison pay rates to afford a single quarter of credit.[12] Prison officials recognized both that cost was problematic and that higher education classes were important to the long-term success of inmates, so began developing a scholarship fund to support tertiary study. In January of 1968, the second quarter of college courses opened. Instructors from Southern Colorado State College taught English and psychology while instructors from Adams State again taught astronomy and algebra. Each course met for three hours a week over a period of eleven weeks. The prison was able to negotiate with the colleges for a fee reduction to make courses more affordable for the inmates.[13]

Soon, inmates began to be tested for math, reading and language skills for academic placement upon entering prisons in the state. Inmates were also asked about career interests for placement into vocational programs. Participation in educational and vocational programs was optional. However, Colorado House Bill 00-1150 gave incentive for inmates to attend classes because they could reduce their sentences by up to sixty days for participation in education. The Correctional Education Program Act of 1990 established an official education division in the Colorado Department of Corrections. The act defined a correctional education program as a “comprehensive competency-based education program for persons in custody of the department.” The objective was to increase educational and vocational proficiency to reduce recidivism and allow for better reintegration into society. Inmates expected to be released within five years were mandated to have priority access to career and technical education programs to provide them with marketable skills for the world outside prison. All prison education curricula had to be approved by the Department of Education or the State Board for Community College and Occupational Education.[14]

Assessing inmate needs

Since 1990, all adult offenders in Colorado have been processed at the Denver Reception and Diagnostic Center, where their mental, physical and educational needs are assessed. Offenders are given the Test of Adult Basic Education with math, reading, and language sections. Each section of the test is graded and the offender is given a “needs” score of one to five indicating an educational placement level. For example, a score of one would place an inmate at college level while a score of four signifies that an inmate is functionally illiterate. Inmates with “needs” scores of one and two are eligible for career and technical education training. Inmates with scores from three to five are placed in academic education classes.[15] This breakdown of the academic needs of the inmates shows how much progress has been made in the way the state views and handles the necessity of education for inmates. Colorado has worked to find a test that it believes best assesses the needs of inmates. It also attempts to provide the necessary programs for inmates because the DOC and the state legislature alike have realized that education is key to an inmate’s rehabilitation.

Educational requirements for federal prisons differ from the state regulations. In the Cañon City and Florence area, where both prison systems are represented, the development of educational programs in the federal prisons has lagged behind those in state prisons. In the early 1980s all federal inmates who did not pass sixth-grade level math or reading were required to attend a literacy program for ninety days. By 1990, federal inmates were required to attend classes until they achieved a twelfth-grade literacy level and completed a high school equivalency degree. If the inmates refused, they were given the lowest-paying prison jobs and might be subjected to disciplinary actions. Tougher literacy standards were meant to lower recidivism rates in the belief that literate people would be able to function better in society after release. Attendance also increased an inmate’s chances of being placed in a post-release halfway house in order to support his reintegration with society.[16] Today, all federal prisons offer literacy, English as a Second Language, parenting, and wellness classes. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, “parenting classes help inmates develop appropriate skills during incarceration. Recreation and wellness activities encourage healthy life styles and habits.” In addition, “institution libraries carry a variety of fiction and nonfiction books, magazines, newspapers, and reference materials. Inmates also have access to legal materials to conduct legal research and prepare legal documents.”[17]

Federal inmates are encouraged to meet a minimal literacy requirement as part of a rehabilitative program, not all federal correctional facilities are required to provide educational opportunities. For example, the Federal Prison Camp, FPC Florence, opened in July of 1992 without education, recreation, furlough or halfway house programs. The inmates protested the lack of programs, holding a hunger strike to express their dissatisfaction. They also gave prison officials a written list of grievances. The response from the executive assistant to the warden was that “the Federal Bureau of Prisons program statement allows for many things. That does not mean every institution has to offer them.”[18] The prison camp relocated the organizers of the strike to other prisons to have disciplinary hearings.[19] The inmates were dismayed by this response to their complaints about the facility, but had effectively no recourse. In contrast to the lack of programs at FPC Florence, the Federal Correctional Facility in Florence has consistently provided educational opportunities. In 1993, inmates there were given educational, psychological and medical examinations before they could begin work. The prison also provided GED and ESL courses.[20]

Vocational programs

Although federal and state prisons have developed education programs at different times, vocational programs appeared in both systems at around the same time and offered similar courses. In the 1985-1986 school year, 2,463 inmates took academic or vocational courses in Colorado prisons. [21] The vocational courses included commercial art, carpentry, woodworking, dental prosthetics, welding, office equipment repair, appliance repair, small engine repair, barbering, meat cutting, business and office education, word processing, industrial maintenance and landscape management. Inmates who completed vocational courses received credentials authorized by the State Board of Community Colleges and Occupational Education. In 1994, the Federal Correctional Facility offered a cabinet-making course, coupling “education with hands-on training.” Seventeen inmates participated in the year-long course, working in cabinetry six hours a day. They started in the classroom studying a book on cabinet making and then put their knowledge to use in the workshop.[22] Today, the Federal Correctional Facility offers vocational courses in computer information systems, custodial training, customer service, carpentry, machine technology, renewable energy, and welding technology.[23]

The Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility offers similar vocational courses in computer information systems, cosmetology, custodial training, customer service, and food production management.[24] These courses are taught because they are growing fields of work. More people are needed to work in basic public service job fields. Inmates with knowledge of custodial work or customer service can apply those skills to many different jobs, thus giving them more opportunities for employment in the world outside prison. In 1980, Territorial provided a dental lab technician program. Six inmates enrolled who were due to be paroled in the following few years. The program was a collaboration between the Pueblo Vocational Community and the State Division of Vocational Training. Classes met for six to eight hours a day for five days a week. This program involved ten months of training. Once the inmates were released they would only need to participate in a six- to eight- month internship in order to become qualified to work as dental technicians.[25] This opportunity for dental training exemplifies a vocational program relevant to the outside world and helpful in released prisoners’ eventual job searches. Similarly, in 1974 the state penitentiary provided a wastewater treatment program. Thirty-eight inmates participated in the three-month program. They were taught math, chemistry, microbiology, hydraulics, practical wastewater operations, safety, maintenance and housekeeping. The course gave the inmates a foundation to take the state examination for an operator’s license. The prison even provided the state examination for the inmates to take once completing the course.[26]

Throughout the twentieth century, the quantity and quality of educational programs offered to state and federal inmates increased significantly. According to the head teacher at the New Horizons school in the Fremont Correctional Facility, “behavior change can be accomplished in various ways through education, but not [entirely] because of expanded knowledge… the biggest disability [in inmates] is [a lack of] self-confidence.” New Horizons teacher Nancy Litvack says, “a lot of students have failed their entire lives… they have set themselves up to fail.”[27] The academic system at the prison is designed to foster an environment to help inmates learn so they do not fail. Instead, the inmates gain self-confidence—and that is the central rehabilitative aspect of education in prison.

Studies have shown that inmates who participate in educational programs are less likely to return to prison once released. Educational and vocational programs supporting this goal are offered in the prisons of Cañon City and Florence. The history of the prison education system confirms that incarceration facilities are still discovering the best ways to facilitate education as integral to rehabilitation for inmates. Taxpayer funding for prison schools reduces recidivism, so is cost-effective—but its greatest benefit is to the human persons whose quality of life it improves.

[1] Originally researched and drafted by Ann Holsapple.

[2] “Prisoner-Teachers Want Day Classes,” Cañon City Daily Record, October 9, 1967.

[3] “Ira Sanger Heads School for Prison Inmates Under New Educational Program,” Cañon City Daily Record, April 18, 1956.

[4] “Prisoner-Teachers.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Prison College Classes Open New Quarter,” Cañon City Daily Record, February 8, 1968.

[7] “Prisoner-Teachers.”

[8] “Prison’s First College Session Comes to Close,” Cañon City Daily Record, December 14, 1967.

[9] “Prisoner-Teachers.”

[10] “Prison College Classes.”

[11] “Prison’s First College.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Prison College Classes.”

[14] State of Colorado, Department of Corrections, “Overview of Educational Programs Fiscal Year 2013,” ed.Rick Raemisch, 2014, 3.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Required to Upgrade Skills,” Cañon City Daily Record, October 18, 1990.

[17] “Federal Bureau of Prisons,” accessed November 1, 2015, www.bop.gov.

[18] Tracy Harmon, “Federal Inmates Unhappy in New Home,” Pueblo Chieftain, 1992.

[19] Tracy Harmon, “Half-day Food Strike ‘Disruptive’,” Pueblo Chieftain, 1992.

[20] Tracy Harmon, “Florence Prison Accepts Medium-security Inmates,” Pueblo Chieftain, January 23, 1993.

[21] John Lemons, “Inmate Education: Main Goal Is to Change Attitudes,” Cañon City Daily Record, March 30, 1987.

[22] Tracy Harmon, “Cabinet Making Mixes Education, Hands-on Training,” Pueblo Chieftain, October 27, 1994.

[23] Raemisch, 6.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Bill Finch, “Inmates Wind Up Dental Training, “Cañon City Daily Record, January 17, 1981.

[26] Chris McLean, “Waste Water Treatment Class Has 38 CSP Inmate Graduates,” Cañon City Daily Record, January 29, 1975.

[27] Lemons.