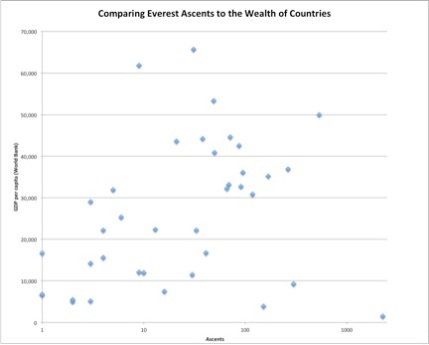

This diagram shows the expected, but nonetheless interesting, correlation between the wealth of countries and the number of successful ascents of Mount Everest from that country. Clearly this is because countries where there is more wealth are more likely to have more people willing to pay the tens of thousands of dollars that it costs to be guided up Everest. These more “representatives” on the mountain means that more people from those countries are likely to summit. But it also reveals some trends that could have deeper implications about certain countries and societies. Now, this does bring up the whole issue of the commercialization of Everest and how it has become a non-climbers mountain in many ways, and I could rant on this topic for hours, but I’ll refrain from that for now because it isn’t essential to explaining the diagram.

“The Main Sequence”

For the most part, countries fall into a moderately strong direct relationship between GDP per capita and the number of ascents on Everest. In this majority relationship, one sees countries like the United States at the very top, with a very high GDP (~50,000) and a very high number of ascents (536). The United States is a perfect example of this relationship, a very high income, and therefore a very high number of people willing to pay to “live their dream” and climb Everest. And on the other end of the main sequence, there are countries like Egypt and Armenia, both with one ascent each, and both with very low GDP’s (in the 6,000 range). Everywhere between there are countries with moderate GDP’s and a moderate number of ascents, filling out the main relationship.

“The Outliers”

While most countries fit into the “main sequence”, there are a few that fall to either side. One that stands out is Nepal, and to a lesser extent China. Both of these countries have very low GDP’s. Yet, they have high numbers of ascents (China with 299, and Nepal with the highest number: 2264). This deviation from the rest of countries can be largely attributed to proximity, Everest being on the border between Nepal and Tibet, and culture. For as long as humans have been climbing Everest, the Sherpa culture of Nepal has been a part of it, acting as guides and porters. Due to this, Nepal has a disproportionately high number of ascents when you look at their wealth. The same goes for China, although to a lesser extent. This shows that, although it has become a big part of the expedition climbing culture, money is not the only thing that matters.

The other outlier group is the countries with very high GDP’s but low numbers of ascents, like Norway and Singapore. Theoretically, there should be lots of ascents from these countries due to their wealth, but there aren’t. This raises the question of how much interest and culture play a role in Everest pursuits. For many, there is a strong desire to conquer and shoot for the highest heights, like for example the United States. That is a deeply engrained part of our culture. But perhaps that isn’t so for every nation.

Data From:

http://www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/everest/

“List of Countries by GDP (PPP) per Capita.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Dec. 2013. Web. 19 Oct. 2013. (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(PPP)_per_capita#cite_note-3)