Ashley Entwistle, ’26, History-Political Science

The two-day World Leaders Action Summit commenced on the first Tuesday of COP29, where the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan invited heads of state and governments to engage in bilateral meetings, high-level roundtable discussions, and special events. Journalists flooded event halls and common areas, shooting footage of leaders as they hurried between meetings.

Meanwhile, the Canada Pavilion took a different approach to the Summit, spearheading its own Indigenous Climate Leadership Day, highlighting voices sidelined by heads of state in climate discussions. This thematic day would have passed me by had I not taken the time to collect a pin from the Canada pavilion, pertinent to my dual-citizenship.

I began Tuesday, November 12, at the USCAN press conference on climate policy in the aftermath of the US election. Alongside three senior policy analysts from think tanks across North America, attendees heard from Sheelah Bearfoot, a representative from the Chiricahua Apache Nation. Sheelah emphasized that, despite tribal sovereignty in the US, Indigenous nations at COP29 were effectively given the same status as NGOs. She expressed concern for the future of tribal recognition in climate discussions––with the outcome of the US election only intensifying her fears.

I returned to the Canada Pavilion in time for the afternoon panel on “Centering Indigenous Knowledge and Leadership in Mitigation and Adaptation: Examples from the Arctic,” moderated by Anne Simpson, policy advisor for the Inuit Circumpolar Council. The panel featured Paul Irngaut, Vice-President of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., Rodd Laing, Director of Environment for the Nunatsiavut Government, and Per-Olaf Nutti, President of the Sámi Council.

Each panelist discussed the importance of Indigenous knowledge in policy, and how it provides holistic and local perspectives on climate risk management. Panelists talked about ways that indigenous knowledge integrates intergenerational and place-based insights in the context of Arctic ecosystems. The key issue, highlighted here, was that world leaders have routinely failed to effectively listen to these perspectives when constructing climate policy. Rodd Laing shared that Canadian officials have made performative attempts to engage with Indigenous communities. Yet, despite these “so-called efforts,” the knowledge they’ve shared has not been integrated into policy. He asked hopelessly: “What do they do with our knowledge?”

This dichotomy is exemplified by the COP process as a whole. This talk on “Centering Indigenous Knowledge” was one of the most important exchanges I’ve attended so far, though it took place in a small pavilion room, with a tiny audience—and all people who already had prior relationships or connections with the speakers. While the audience size was disappointing, I took advantage of the opportunity to engage, staying behind to build on the points raised by the three panelists.

In line with his skepticism toward the COP process, Laing shared his view of a contradiction: climate leaders in Canada are focused on addressing climate change impacts in the global South, yet are largely failing to address the severe effects of climate change on northern First Nations communities in their own country.

“Canada tried to eliminate us,” Irngaut stated, offering context to the historical injustices faced by Canada’s First Nations people. As Canada and other countries continue to divert attention away from their northernmost Indigenous communities in Arctic territories—who are bearing the brunt of climate change regionally—they perpetuate these injustices, albeit in new forms.

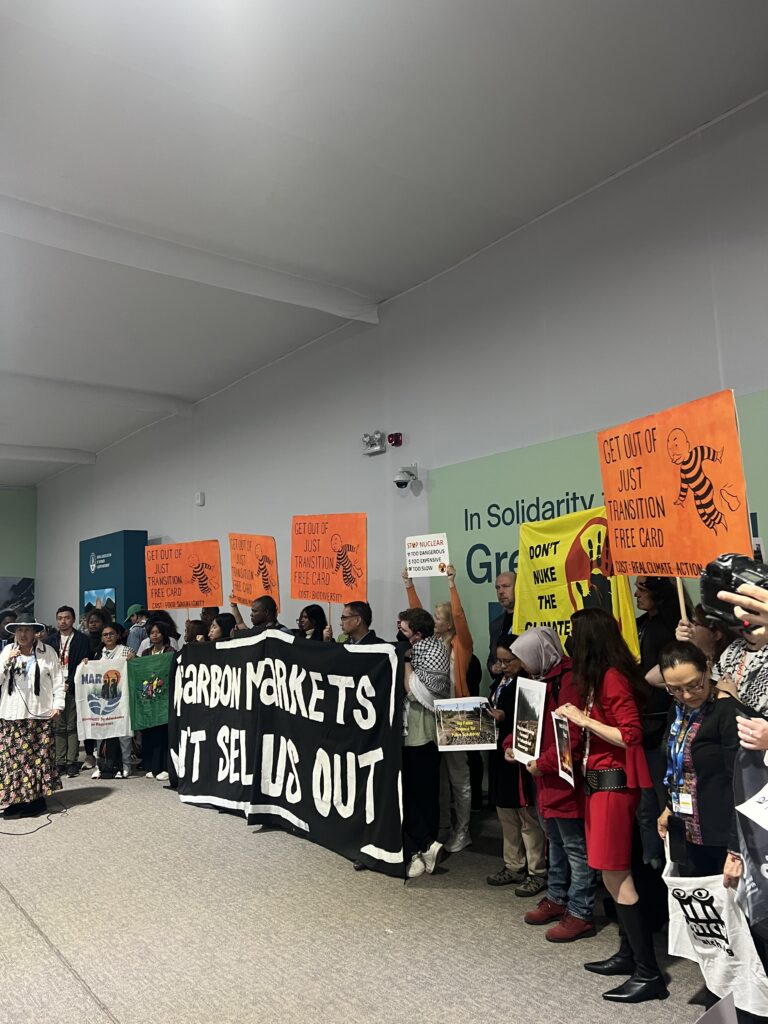

The three panelists emphasized the importance of COP29 in advancing climate justice, yet they expressed frustration in seeing their own nations attempting to address the climate crisis globally, while neglecting it at home. Similar frustrations have manifested themselves in different forms, such as the protest that took place on Thursday, November 14, in the stadium corridor, where activists called out world leaders for promoting false solutions to climate change—solutions that overlooked local Indigenous knowledge.