In 1960, the American National Election Study asked a random sample of Americans how “displeased” they would be if a child of theirs married a person from the opposing political party.1 About five percent of both Democrats and Republicans said they would be displeased.

In 1960, the American National Election Study asked a random sample of Americans how “displeased” they would be if a child of theirs married a person from the opposing political party.1 About five percent of both Democrats and Republicans said they would be displeased.

In 2016, the numbers looked a little different. A similar question appeared on a national survey, and 60 percent of Democrats said they would prefer their child marry a Democrat, while 63 percent of Republicans preferred their child marry a Republican.2

Political polarization — a measure of overlap between the two parties or ideologies — has undoubtedly widened over the past 70 years. This is true at the elite level and the individual level. Ample evidence suggests that Congress is more polarized than ever.3 But what about the public? Voters have certainly become better sorted ideologically into the party system: liberal voters increasingly support the Democratic Party and conservative voters increasingly support the Republican Party. But is the American electorate as polarized as their representatives? Most evidence suggests that elected officials are more extreme than their constituents4, but there is little doubt that voters are more polarized and better sorted than in previous eras.

In my work, I consider the role of ideology in politics. More specifically, I ask questions centered on how our identities as liberals and conservatives affect our behavior and thinking — politically, psychologically, and socially. While party identification has long been the single best predictor of voting behavior, ideology is just as deeply important to Americans, acting increasingly as a social identity, and serving as a guiding force outside of the voting booth. Social identities can be thought of as a person’s sense of who they are based on their group memberships.5 They speak volumes about who we are and how we define ourselves. Being a CC Tiger, for example, is a deep and lifelong attachment for some (perhaps especially those reading this article). For others, being a parent is central to defining them. To still others, being American is fundamental to their identity. Research demonstrates that our ideological attachments operate much like these core identities.

So, why focus on ideology over partisanship, especially when it comes to polarization? Ideological identifications, it turns out, are potentially even more deep-seated than party identifications. Ideology is gut level. That is, it is linked to our morality — our sense of right and wrong — to our personalities, is more closely tied to how we live our lives, and is a strong predictor of our social circles. It is this last component that is particularly fascinating. Social identity theory suggests that we seek to enhance our own self-images, and we do this primarily by sorting the world into in-groups and out-groups. In this thinking, someone who defines themselves by being an American may consider his in-group (America) to be better than other countries. Not only is America the best, the thinking goes, but other groups (e.g., Canada, France) are terrible. This tendency to categorize the world into “us” versus “them” is not only a precursor to societal ills such as racism and sexism, but it’s also an antecedent to political polarization. And this division is particularly strong among liberals and conservatives.

In my own research, I have found that liberals and conservatives stereotype each other — just as social identity theory would predict. But, they stereotype not just on political matters or policy preferences. They do so on matters of morality, too.

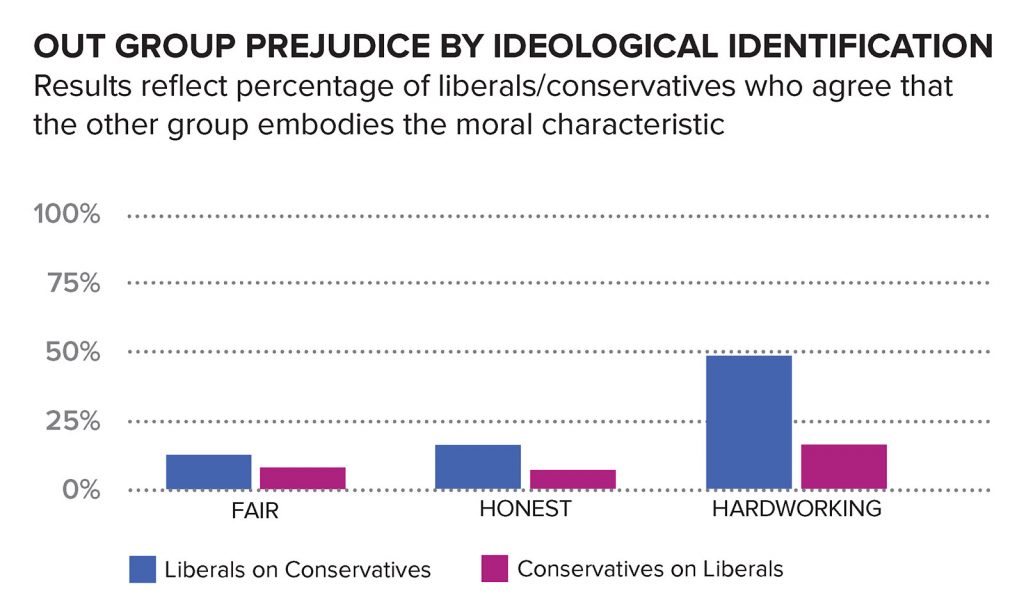

The figure below demonstrates this. In this survey, conducted in 2012, respondents placed themselves on a seven-point ideological scale, ranging from very liberal to very conservative. Later, they were asked a host of questions about how they viewed liberals and conservatives (their own group and the ideological out-group). The figure below draws out a subset of these data, showing the percentage of respondents (by ideological identification) who agree that the other group embodies three central components of morality (fair, honest, hardworking).

The results are astounding and unambiguous. With the exception of nearly half of liberals believing that conservatives are hard-working, liberals and conservatives have highly negative views of their out-group. Conservatives are particularly hard on liberals, with fewer than 10 percent believing liberals are fair or honest. Importantly, these results reflect the thinking of ordinary citizens. The numbers among elites are even more disparaging.

Is it any wonder, then, that we find ourselves in a politically polarized America? Beyond the infusion of morality into politics, many other factors have contributed to this widening. A few of the most commonly studied are gerrymandering, geographical sorting, growing racial and ethnic diversity, negativity in an increasingly bifurcated media, and income inequality.

In fact, compelling research demonstrates that it’s not only that income inequality and polarization are happening in tandem — it’s that income inequality has a causal effect on political polarization6. This is true even after controlling for other common predictors of polarization. This particular realization can make ordinary citizens feel helpless: What can we do to combat income inequality in meaningful ways? Some individuals, of course, are equipped to take tangible, personal action. Those who own businesses can pay living wages, offer paid family leave, extend apprenticeship opportunities. Those with political control can advocate for a host of public policies that dampen the divide among affluent and less well off Americans.

But for most, the division we observe in the daily news and feel at work or even among our own family members seems irreparable. The reality of ideological stereotyping on moral grounds only serves to compound these feelings.

So, what do we as citizens do to combat this increasing shift toward division?

So, what do we as citizens do to combat this increasing shift toward division?

I considered this very question in the Baccalaureate address at Colorado College in May of this year. And my suggestion was simple: learn to pivot. Push back against the tendency for division, the tendency in our everyday lives to focus on what divides us and makes us different. This tribalistic thinking has become the default for many.

Pushing back begins, in my opinion, in our social worlds. It happens simply, but will challenge your routines and your thinking.

In your thinking, it requires you to focus on a set of principles that unite us. Develop a personal guiding philosophy in which differences are less important: a forward-looking, progressive vision, that a broad range of people, with varying identities and life experiences, can see and say “yes, I see myself in that vision. Those are the principles I stand for, too.” Framing issues in terms of basic values brings people together, and sends a signal that connection, not estrangement, is the goal. This, I believe is our strongest tool to combat divisiveness.

In practice, you can do this by engaging the people around you. Especially engage those people who don’t look like you, who aren’t in your social circle, who grew up in a different neighborhood than you, who you believe think differently from you. Mutual understanding is the foundation. When you disagree with someone about solutions, do not thusly assume that a real problem doesn’t exist.

Critically, in these engagements, the goal is not to change others’ minds. In fact, that’s highly unlikely. (Don’t believe me? What’s the most important issue to you in politics today? Climate change? Death penalty? Abortion? Imagine changing your opinion 180 degrees. Yeah, didn’t think so.)

Instead, the goal is coming to the realization that many other peoples’ opinions have merit, too. This leads to mutual understanding and critically, mutual respect. This is the key to pivoting on tribalistic thinking. The first step to that is recognizing your own.

In your everyday life, how do you accomplish all of this? The simplest, and most intimate way, in my opinion, is by sharing a meal. I am not being simplistic here. Sharing a meal with someone is one of the most intimate and powerful actions you can take. It’s binding. Eating the same food together increases trust and cooperation between people.7 Talk about your philosophy, what principles guide your thinking, and why they do. Be equally curious about your dinner companion’s thinking, principles, and motivations.

This is learning to pivot. This is pushing back. Bon appétit.

To read Professor Elizabeth Coggins’ Baccalaureate address from May 2018, “Learning to Pivot,” go to: 2cc.co/coggins2018

1 Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, Yphtach Lelkes. 2012. “Affect, Not Ideology. A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly Volume 76, Number 3: 405-431.

2 Vavreck, Lynn. “A Measure of Identity: Are You Wedded to Your Party?” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/upshot/are-youmarried-to-your-party.html

3 Hopkins, Daniel J. and John Sides. 2015 Political Polarization in American Politics. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

4 Bafumi, Joseph and Michael C. Herron. 2010. “Leapfrog Representation and Extremism: A Study of American Voters and Their Members of Congress.” American Political Science Review Volume 104, Number 3: 519-542.

5 Tajfel, Henri and J.C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In W.G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

6 McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. 2016. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology & Unequal Riches. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

7 Vedantam, Shankar. 2017. “Why Eating the Same Food Increases People’s Trust and Cooperation.” Podcast audio. https://www.npr.org/2017/02/02/512998465why-eating-the-same-food-increases-peoples-trust-and-cooperation