Other Schools Looking at CC’s Model

When Professor of Anthropology Sarah Hautzinger started preparing her spring courses in January, she did not envision teaching a Block 8 course in which the major project would be in direct response to “COVID-19” and “social distancing.” Indeed, those words would not have appeared on her syllabus in January, February, or even mid-March. But into Block 7, when her vision for the upcoming 200-level anthropology course began taking shape, those concepts were foremost in her mind.

Assistant Professor Amanda Minervini, who teaches in CC’s Italian program, originally planned to teach a gastronomy class in Italy during Block 8. When the coronavirus pandemic forced her to make new plans, she created a course specifically with the pandemic and online format in mind — Storytelling During the Time of the Plague: Boccaccio and “The Decameron.”

Such is the flexibility of CC’s Block Plan. Rather than being locked into a traditional 16-week semester course, Hautzinger and Minervini were able to quickly adapt their courses so the focus was immediately relevant to what was taking place across the country — and the world.

That ability to react and adapt quickly is one of the advantages of the Block Plan, says Chad Schonewill ’03, assistant director of solutions services. “I mean, if there’s any place geared to reacting quickly … that’s bread and butter for the whole college, but certainly for IT,” he says.

The book Minervini based her class on, “The Decameron,” by the 14th-century author Giovanni Boccaccio and set in 1348 Italy, is a collection of 100 stories told by a group of young adults sheltering in the Tuscan countryside having left Florence to escape the plague. It’s a far cry from a gastronomy class in Italy, but completely relevant to the times, and Minervini credits the Block Plan for its nimbleness to adapt courses to changing circumstances. “There is no other system that would allow me to develop and teach a whole course in response to a rapidly changing situation like this,” she says.

Hautzinger’s class, The Body — Anthropological Perspectives, which included a project called “Social Bodies While Distanced,” also was unique to this moment in time, something the CC anthropologist loves about the Block Plan. “Every block is its own story,” says Hautzinger. “The Block Plan moves away from cookie-cutter courses. Each block is like a bead added to a string; the color and tone are idiosyncratic to that moment. The whole month is tied to that experience, to a single course and not multiple courses.”

Adjustments Add Flexibility to Academic Calendar

The block format is attracting interest from other colleges and universities because of the flexibility it offers, not only for course content, but also for scheduling.

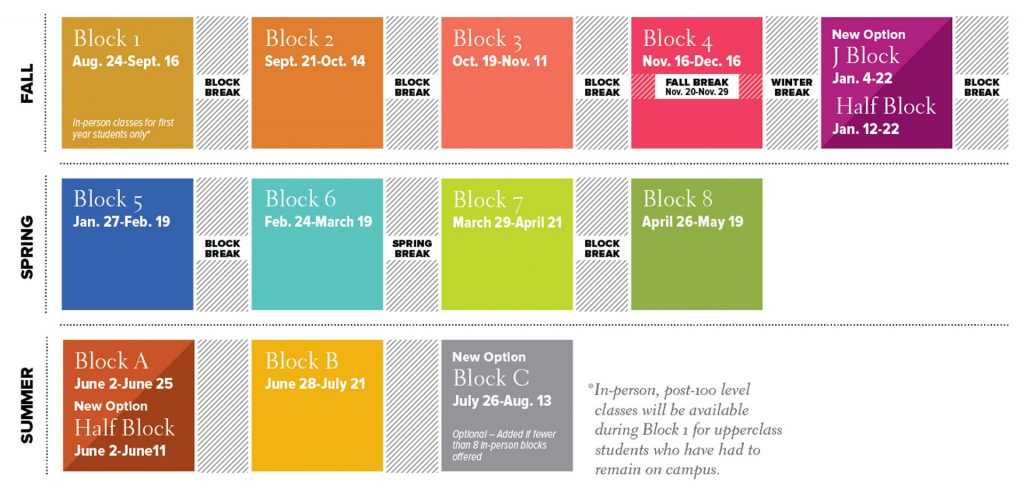

The flexibility of the Block Plan allowed CC to adjust its academic calendar for the 2020-21 academic year, broadening scheduling options for students and providing more value to them during this unpredictable year. The addition of a new January “J Block,” in addition to half blocks and summer courses, means that students can take 10 blocks of courses for the usual 8-block tuition cost this academic year. Or students may choose to shift their academic year’s start and end dates, while still meeting their requirements for the year. Currently, CC plans to offer 11 blocks, beginning in August and continuing through Summer 2021, with the ability to add a 12th block if needed.

Former Provost Alan Townsend, in an “All Things Considered” interview that aired on NPR in May, said, “Colleges that use [block scheduling] have the opportunity to change the way classes look every three weeks — since there are multiple start and stop points. With a semester, you have only a single start and then, often 16 weeks later, an end.”

This calendar, with multiple options, allows students to adjust their schedule as needed. In addition to the “J Block,” CC is offering its usual credit and non-credit Half-Block classes, additional summer Half Blocks will be added, and a summer Block C may be added if needed.

“Different students can make different choices. That’s really hard to do with a semester-based system, but the blocks allow us to do that,” Townsend said in the NPR interview, which addressed “Six Ways College Might Look Different in the Fall.”

Other Schools Looking at CC’s Model

CC has been contacted by various small liberal arts colleges, K-12 schools, and universities, including research universities and an Ivy League institution, seeking information about block teaching, says Traci Freeman, executive director of the Colket Center for Academic Excellence, and Jane Murphy, associate professor of history and director of the Crown Faculty Center. Schools want to know the benefits and challenges of the block structure, how faculty should design courses for the intensive format, what works and what doesn’t, and what challenges students face learning at an accelerated rate.

“They are interested in hearing how the Block Plan works and how to prepare faculty and students to teach and learn in a block system,” says Freeman. “They are also interested in the impact of the block on student life, academic support, and advising.”

Murphy and Freeman co-organized the Institute on Block Plan and Intensive Teaching and Learning, originally scheduled to be offered in-person this summer, in connection with the 50th anniversary of the Block Plan. With interest in block programming intensifying because of COVID-19, Murphy and Freeman restructured elements from the original program and designed a remote version, offering two webinars in July with colleagues around the globe. Among those presenting at the July webinar were Freeman and Drew Cavin, director of the Office of Field Study. Freeman and a colleague from Cornell College — a private liberal arts college in Mount Vernon, Iowa, that has been teaching a Block Plan model since 1978 — co-presented “Teaching and Learning in Block Plan and Intensive Courses,” and Cavin presented “Active and Experiential Learning Online.”

Additionally, Freeman, Murphy, and Mike Taber, professor of education, traveled to China last fall to consult with administrators and faculty at Duke Kunshan University, which has a seven-week term. This spring and early summer, Freeman and Murphy presented to several hundred faculty and administrators at multiple institutions, in addition to holding conversations and sharing materials with folks across the country. Among their presentations was “Teaching and Learning for Intensive, Time-shortened Courses,” which Murphy and Freeman delivered in June to faculty and administrators at three small liberal arts colleges.

Murphy says other schools are especially interested in hearing about introductory STEM and other content-heavy classes, reading, writing, and research.

“We answer these questions honestly. Research would indicate that time-shortened courses are no better or worse for student learning than semester courses,” says Freeman. “What does seem to matter in a time-shortened course is the faculty member and their pedagogical choices. This said, the Block Plan does put certain pressures on the processes of teaching and learning, which faculty designing classes should take into account. And we make the point the Block Plan alone is not what makes CC special, but rather it is the teaching and learning culture of the institution that has developed alongside the Block Plan that matters most.”

Murphy agrees. “We advise them that classroom climate, inclusive pedagogies, and meaningful relationships between students and student-to-faculty also is really essential to a successful block,” she says. “These relationships with one another and the material motivate students to do the intense work we are asking.”