When friends and parents of the Colorado College extended family saw the dramatic pictures of the Waldo Canyon Wildfire just west of campus last June, they were stunned and alarmed over what they were seeing. How could this happen? Was our beloved campus in danger? Some called in and were relieved to learn that the college was never threatened and indeed had become a haven as a temporary shelter for some of the terrified residents who had to flee their homes. When it was over, 346 of those houses had been burned to the ground with damage exceeding $352 million. Two people died. It was to be the most destructive wildfire in Colorado history, eclipsing the High Park fire west of Fort Collins, which had earned that dubious distinction only two weeks earlier.

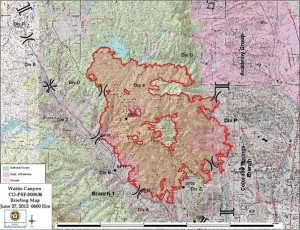

The fire was reported on Saturday, June 23, below the Rampart Range Road and near the popular Waldo Canyon Trail in the Pike National Forest. It was a dry and windy afternoon, and by evening the fire had spread to 2,000 acres. It burned all night and the next morning evacuations were ordered in Manitou Springs and towns up Ute Pass. Some subdivisions above Garden of the Gods became threatened that afternoon and U.S. Highway 24 was closed. The extreme burning conditions continued into Monday, June 25, as the fire spread to 4,500 acres. The flames jumped containment lines on the Rampart Range Road and there was great concern that it might get into Queen’s Canyon above Mountain Shadows subdivision and the landmark Flying W Ranch.

The fire was reported on Saturday, June 23, below the Rampart Range Road and near the popular Waldo Canyon Trail in the Pike National Forest. It was a dry and windy afternoon, and by evening the fire had spread to 2,000 acres. It burned all night and the next morning evacuations were ordered in Manitou Springs and towns up Ute Pass. Some subdivisions above Garden of the Gods became threatened that afternoon and U.S. Highway 24 was closed. The extreme burning conditions continued into Monday, June 25, as the fire spread to 4,500 acres. The flames jumped containment lines on the Rampart Range Road and there was great concern that it might get into Queen’s Canyon above Mountain Shadows subdivision and the landmark Flying W Ranch.

Tuesday, June 26, proved to be the worst day of all. East winds drove the fire all the way to Rampart Reservoir, and then shifted to the south pushing it toward Queen’s Canyon to the north. The fear was that once it reached the heavily forested canyon, the flames would race up the canyon like a blow torch. This had occurred in other fires in the Front Range. Instead, the very worst-case scenario happened; a perfect firestorm developed when a late afternoon dry thunderstorm came from the west around the north side of Pikes Peak. When the storm reached the head of Queen’s Canyon, a huge downdraft with 65 mph winds developed and pushed the fire downslope toward the residential areas south of the Air Force Academy. As evening came, a huge fire ball descended into the neighborhood of Mountain Shadows. The terror of the spectacle was captured on cell phone cameras as people raced for safety. Fortunately, it was an orderly retreat assisted by police from many communities.

There are many lessons to be learned, some of them repeat lessons. The combination of dry forests, high winds, and homes being built in areas prone to wildfire all contributed to the disaster. The unusual combination of circumstances that drove the fire proved to be truly extreme. Few who witnessed it will ever forget it.

Keith Argow ’58 was actively involved with the local community while at CC, working with the U.S. Forest Service and serving as student body president and commanding officer of the ROTC cadet detachment. He later became a USFS district ranger and fire boss, and is publisher of National Woodlands Magazine, and Fire Lookout Magazine in Washington, D.C.

Keith Argow ’58 was actively involved with the local community while at CC, working with the U.S. Forest Service and serving as student body president and commanding officer of the ROTC cadet detachment. He later became a USFS district ranger and fire boss, and is publisher of National Woodlands Magazine, and Fire Lookout Magazine in Washington, D.C.