Another example in the long line of injustices against the Navajo Nation, over 2,000 Navajo farmers have been unable to use their normal water stream in the aftermath of the Gold King Mine spill of 2015.[1] On August 5th, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was checking up on Gold King, attempting to clear debris from the long closed mine. Not following protocol in multiple instances, 3 million gallons of toxic water were released into the Animas River, turning it a vile shade of yellow.[2]

Animas River in the wake of the Gold King Mine spill, August 2015. (Jerry McBride, Durango Herald)

This pernicious water stream began in Silverton, Colorado, an old mining town that has fallen on tough times. At its peak in the early 20th century, Silverton was thriving; 2,000 of its residents worked for one of the many mines in the area. However, this prosperity is fickle in the mining industry and eventually the amount of jobs dried up and people were forced to find other sources of income. Considering the vast beauty of the American West, becoming a tourism spot often bears a fruitful source of income. Towns such as Breckenridge, Aspen and Telluride have all adapted out of mining into popular tourism destinations that boast world class skiing and hiking.

Silverton, on the other hand, has had a tough time letting go of its mining past. Johnathan Thompson of High Country News described the sentiment of one local: “He mourned the loss not just of jobs and money, but also of authenticity and, in a way, identity. Mining is real, genuine palpable; tourism is entertainment.”[3] Sympathy can be felt towards the people of Silverton for their loss of identity, but mining has a far greater impact on the surrounding environment and has the power to harm many communities located outside of the Silverton area. Even as late as 2014, a mining company, Colorado Goldfields, existed with the purpose of revitalizing the mining industry in and around Silverton. Companies like Colorado Goldfields have prevented the local mines from receiving Superfund status, which designates especially detrimental areas and provides the necessary resources to clean them. This nostalgia and disregard for the environment has left many downstream communities feeling the burden of this harmful industry.

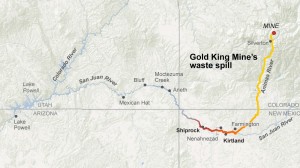

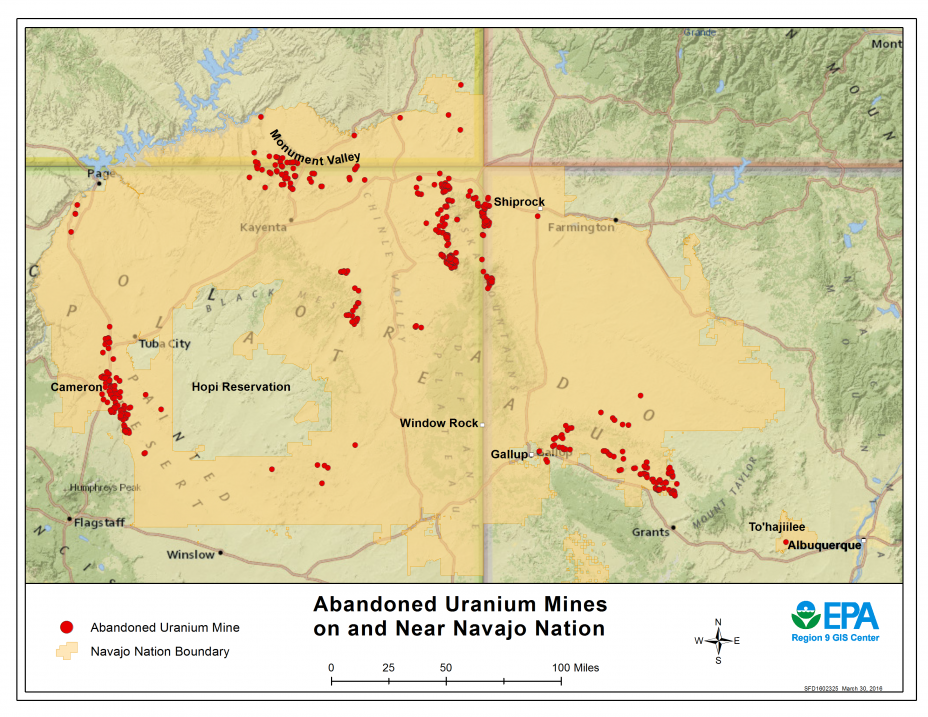

In the wake of the Gold King Mine spill, the millions of gallons of toxic wastewater flowed down from the Animas River, eventually merging into the San Juan River. The San Juan River flows through the land of the Navajo Nation, who have faced a multitude of environmental injustices over the course of their history. Currently, there are around 1,100 abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation land causing detrimental long term health effects.

Spill path of toxic water into New Mexico and Utah. (Lorena Iñiguez Elebee, Los Angeles Times)

As mentioned above, over 2,000 farmers have lost their water stream, causing crops to dry up. In the little over one year that has passed since the spill, the Navajo Nation feel that the EPA has not done an adequate job in the clean up and restoration of the affected areas, and have even filed a lawsuit against the agency.[4] The EPA has not done enough testing on the river sediment, which could cause long term health effects. One Navajo local from Mexican Water, Utah, was skeptical of the EPA conclusions: “We know this river. We know the sediment moves slowly and that the worst of the pollution is yet to come.”

That same community of Mexican Water had not seen any help from the EPA for months after the spill. This area is very isolated, there are no nearby paved roads and the nearest grocery store is 35 miles away. Even areas that saw relief from the EPA complained that the quality was not up to their standards. Water is sacred to the Navajo; they use it in its pure form for many religious ceremonies. Therefore, they have still not deemed the San Juan river water usable, even if the EPA has said otherwise.

Who is to blame for this environmental disaster? The EPA has taken responsibility for the spill, but do they deserve 100% of the criticism? Ethel Branch, the attorney general of the Navajo Nation, stated, ”From the very beginning, the EPA tried to shift the conversation to the overwhelming nature of dealing with abandoned hard rock mines in the West, in my view to dilute the significance of what occurred and the need for them to be accountable and to clean up the contamination or address it in some way.” Silverton residents have fought for the revitalization of the mining industry, even in recent years. Fearing the stigma of Superfund status, residents rejected the EPA’s help multiple times.[5] However, Ms. Branch brings up a fair point. Just because the EPA was put in a tough cleanup position does not discount the problems of the Navajo Nation. They still do not have a reliable water stream for farming or religious activities. The burden of responsibility lies with both the EPA and the mining community of Silverton. A higher priority needs to be placed on cleanup efforts in the Navajo Nation as they are a low income community that was not at all responsible for this environmental disaster.

[1]http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/print/2015/08/21/navajo-crops-drying-out-san-juan-river-remains-closed-after-toxic-spill-161461

[2]http://www.forbes.com/sites/wlf/2016/02/24/accountability-for-thee-but-not-for-me-epa-the-animas-river-and-environmental-crime/#584fa17b6d4b

[3]http://www.hcn.org/issues/48.7/silvertons-gold-king-reckoning

[4]http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/16/politics/navajo-lawsuit-epa-animas-river/

[5]http://www.journalgazette.net/news/us/Mine-cleanup-aid-was-rejected-8195108

Native tribes are defined by the Supreme Court as “dependent sovereigns” because “their sovereignty predates that of the United States, but that it is nonetheless internal to, and dependent upon, the federal government[3]“. Sarah Krakoff defines environmental justice for tribes as “the achievement of tribal authority to control and improve the reservation environment,” making a respect for tribal sovereignty central to tribal EJ issues.

Native tribes are defined by the Supreme Court as “dependent sovereigns” because “their sovereignty predates that of the United States, but that it is nonetheless internal to, and dependent upon, the federal government[3]“. Sarah Krakoff defines environmental justice for tribes as “the achievement of tribal authority to control and improve the reservation environment,” making a respect for tribal sovereignty central to tribal EJ issues.

act was passed in response to a push by the Bush administration to increase the use of nuclear power as a clean energy source. In 2013, the Navajo Nation Council voted to block Uranium Resources Inc. from building new mining projects on the reservation

act was passed in response to a push by the Bush administration to increase the use of nuclear power as a clean energy source. In 2013, the Navajo Nation Council voted to block Uranium Resources Inc. from building new mining projects on the reservation