Climate change is an issue that cemented its place in the public consciousness years ago; ask anyone about it and they’re sure to have an opinion. The sad thing is that most people are unaware of the full story, which leads to confusion and a continuation of the political divide surrounding climate change. The truth is that the issue goes deeper than I ever knew before this class, and some of it’s more than a little unsettling.

We’ve all heard by now (whether we believe it or not) that greenhouse gas emissions, caused by our modern industrial society, are changing the makeup of the atmosphere and causing global warming. Unfortunately, this is where the conversat ion often ends. Global warming/climate change has become an extremely divisive issue in politics. The general state of affairs seems to be that the political left believes that climate change is human caused while the right believes that either we are not responsible or it’s not happening.

ion often ends. Global warming/climate change has become an extremely divisive issue in politics. The general state of affairs seems to be that the political left believes that climate change is human caused while the right believes that either we are not responsible or it’s not happening.

It doesn’t really make sense that there can be such a divide on an issue that is scientifically based, right? Well like Sarah talked about in the last post, here in PS356, we’re all about bringing different academic perspectives together. In the wider world, though, this doesn’t often happen. Scientists are often not great at getting their point across to people outside the sciences. Politicians and political pundits are usually not well versed in scientific knowledge and may spread misinformation when they talk about something they don’t truly understand.

If you take time to learn about the processes of the natural world that are driving climate change, it becomes hard to deny it. Harder still is forgetting about it once you know what the extent of the consequences might be.

So the truth goes something like this:

We know from geological studies that at no time in the last 650,000 years has the Earth’s atmosphere contained more than 290 ppm (parts per million) CO2. By 2010, however, the count had risen to 389 ppm and it is now rising by more than 2 ppm per year. Looking at the second half of the 20th century (when things really started accelerating), we see that global temperatures have risen in tandem with CO2 concentration. What’s more, over the same period, sea levels have been rising and glacier volume has been shrinking dramatically.

I saw the effect on glaciers first hand this summer when backpacking through Glacier National Park. Photos of the park from 80 years ago held up to the current landscape show an astonishing change. Sheets of ice used to cover entire mountains and now they’ve shrunk so much that it can be difficult to distinguish the glaciers from mere snow fields. Official estimates say that the glaciers in the park will be completely gone in about 20 years.

When I learned this fact, I was truly upset, as Glacier National Park is, for many, myself included, the most beautiful of the National Parks. I’ll be sad to see the day when it can no longer live up to its namesake.

Now we know the basics in regards to proof of climate change, but the possible future effects are where things get really interesting.

It’s a common concern that melting polar ice caps will lead to sea levels rising, but that’s not the only role the ocean has to play in this. Oceans are a lot more complex than we usually think about; they’ve got layers. The upper layer acts as a massive carbon absorber, pulling in CO2 from the atmosphere and trapping it in the water. This might sound like a good thing, since it’s reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. The problem, though, is that this carbon is making the ocean more acidic, which then causes problems for marine organisms. Further complicating marine life is the heating of the oceans, rounding out a one-two punch of disruptive change to the environment that the organisms evolved in.

Ocean heating also brings up problems for the atmosphere, as it is causing the trade winds to intensify. These wind patterns got their name from the days when they propelled sailing ships across the oceans, allowing for European expansion. Now, they’re stirring up the oceans and leading to mixing of the aforementioned layers. The deep layers of the ocean contain massive, ancient carbon deposits which are now being brought to the surface, releasing even more CO2 into the atmosphere.

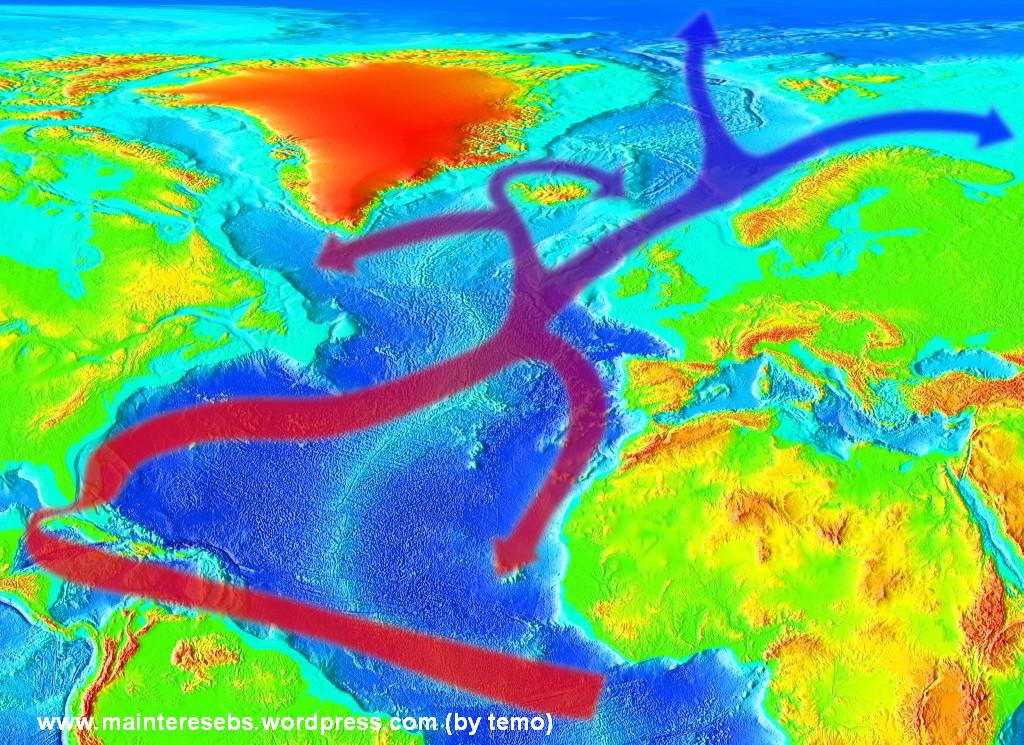

Now, if you look at a world map, you’ll see that Western Europe is at the same latitude as the northern expanses of Canada that are largely frozen. Well why should you be able to lie on a beach in Spain while you need a parka to survive in Canada? It’s because of a process called Thermohaline Circulation, sometimes called the Great Ocean Conveyor. This is the scientific name for the ocean currents you probably learned about in middle school. Water that is heated in the tropics travels northward on top of the oceans, as warmer water is less dense. Once it reaches the northern latitudes, the water cools and sinks to the bottom of the ocean and is pulled back to the equator. The particular current that heats Europe, the Gulf Stream, flows along the eastern United States and then cuts across the Atlantic towards Europe and Africa, leaving Canada out in the cold.

Now, if you look at a world map, you’ll see that Western Europe is at the same latitude as the northern expanses of Canada that are largely frozen. Well why should you be able to lie on a beach in Spain while you need a parka to survive in Canada? It’s because of a process called Thermohaline Circulation, sometimes called the Great Ocean Conveyor. This is the scientific name for the ocean currents you probably learned about in middle school. Water that is heated in the tropics travels northward on top of the oceans, as warmer water is less dense. Once it reaches the northern latitudes, the water cools and sinks to the bottom of the ocean and is pulled back to the equator. The particular current that heats Europe, the Gulf Stream, flows along the eastern United States and then cuts across the Atlantic towards Europe and Africa, leaving Canada out in the cold.

This process is dependent on the salinity of ocean water. Salt is what causes the dramatic differences in heat content and water density that allow for the currents. We face a problem, though, as the melting of the polar ice caps is releasing fresh water into the oceans, diluting the salt content. If the salt content drops too low, the Great Ocean Conveyor could shut down, plunging the northern parts of the world into an ice age. While this sounds pretty grim, keep in mind that another option is that the release of deep ocean carbon could lead to a runaway greenhouse effect, making our atmosphere look more like that of Venus than the one we’re used to on Earth.

Forget The Day After Tomorrow; I’m pretty terrified of the prospect of Earth trying to be like Venus. The environment on Venus is so harsh that the first space probe that entered the atmosphere was destroyed in under an hour. Think about what that means for a human.

The information is out there, and people need to know so that we can gain momentum in the effort to address climate change. I may be biased, but I think the science behind all this is not only worth knowing, but also pretty interesting. The issue with climate change is that its consequences are not yet easily felt, but if we wait to act until we see those definite consequences, we’ll be too late.

So go out and tell your friends, tell your mom, just tell everyone, because this problem isn’t going away. Unless you have some fantasy about riding a woolly mammoth across the frozen tundra of New York, you have a stake in this.