Coming to Baca makes perfect sense for a block on Cultural Astronomy. It’s not just the wide, largely un-light-polluted sky, but something about the sense of quiet tranquillity that engulfs Crestone, a site of important spiritual convergence. There’s something befitting of this mindful environment, as we turn our eyes to the night sky. Considering celestial bodies, I think, demands respect of the wider forces that govern our universe – how can I fully appreciate the gargantuan gravitational orbits of planets in our solar system, amid the frantic hustle of campus life at Colorado College.

We arrived to Baca on Wednesday of the first week of the block, and on Thursday travelled over three hours down to Chimney Rock, a site of cultural astronomical importance for the ancestral Pueblo people of the Southwest. From Chimney Rock, it is thought that people converged to observe the moon as it rose between two tall chimney-looking rock stacks, an occurrence called the Major Lunar Standstill. The orbit of the moon around the Earth oscillates, as it is offset by about 5 degrees from our meridian. As such, the moon rises and sets at different points on the horizon through the year – one can observe this on a weekly basis. Every 18.6 years, however, the moon completes this oscillation, and its point of rising and setting appears to freeze for a period of time – the moon rises at the same location on multiple nights. This is a Major Lunar Standstill, and Chimney Rock is thought to be the only place in the world with a geological formation that naturally serves as a viewing platform. The people who lived at Chimney Rock were here for this purpose – to study the moon and the stars and the sun and their relationship to each other. Dwellings and Kivas – ceremonial buildings – were built at the site to house such populations. At the time of the Major Lunar Standstill, it is thought that people from across the Chaco region flooded to Chimney Rock, which exists as a natural amphitheatre, to observe the celestial phenomenon.

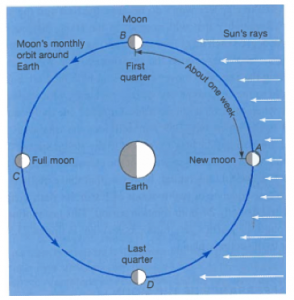

Much of our first week in class has been focused on the moon and its phases. We all know that the silver orb of in the night sky is not a light shining from the moon itself, but a reflection of the sun’s luminosity. But if the moon acts as a mirror for the sun’s rays, then how does the angle of the moon and the sun, relative to Earth, impact the reflection we may see in Colorado? In other words, how are the phases of the moon dictated by the position of the sun and the moon, again relative to Earth? For the moon to be full, the sun’s luminosity must shine directly upon the side of the moon that is visible to us on Earth. Thus, the Earth and Moon’s orbits must be such that the Earth is between the Sun and the Moon. We see a new moon, on the other hand, when the Moon lies between the Sun and the Earth. This is because most of the Sun’s luminosity is reflected back out to space towards the Sun, where we cannot see it, while only a slither of light – a crescent moon – is reflected back to us here on Earth.

In our second class of the block, Professor Dick Hilt asked how many of us had seen the moon the night before. I’m not sure that anyone raised their hand, and to clarity, it was not a cloudy night. Going forward in the block, I will make an effort to pay more attention to the sky around me at night, and observe the celestial bodies as communities through history have done.