Hello CC!

My name is Hannah Baum, and I am a sophomore in Professor Karen Roybal’s Southwest Studies class, called Art, Power, & Resistance.

The focus of our first week was art, embodiment, and tradition. Before starting to discuss the focus of the course, Southwest art, culture, and history, we spent two days discussing and learning how to view and interpret art. As viewers, we were introduced to the practice of consuming art as a four-step process: look, describe, think, connect. However, we quickly realized that this process is far more complex and convoluted than it appears, especially because of the Eurocentric ideologies that tend to govern traditional museum spaces and dominant conceptions of fine art.

In his 1994 essay we read for class, Dr. David Fenner presents the potential issues with choosing to or not to define art, which he calls the “meaning argument” and the “criticism argument,” respectively. Through this reading and class discussions of what is and is not art, I concluded that there isn’t and will never be one, ubiquitous definition of art. I’m still not sure how I, personally, define art, though I think this inability to define is a beneficial thing, as it allows for the consumption and interpretation of art to exist outside of conventional, often colonial-imposed boundaries. In my attempt to define art, I noticed how historians, scholars, and observers define certain things created for utilitarian use, like bowls, rugs, and ceremonial instruments, as art. I never considered how we might label something as “art” to extract meaning for historical context. While I think it is important to acknowledge art as symbolic, analyzing it from an exclusively historical lens can perpetuate the Eurocentric view of Indigenous art and culture as finite, extinct, and existing only in the past.

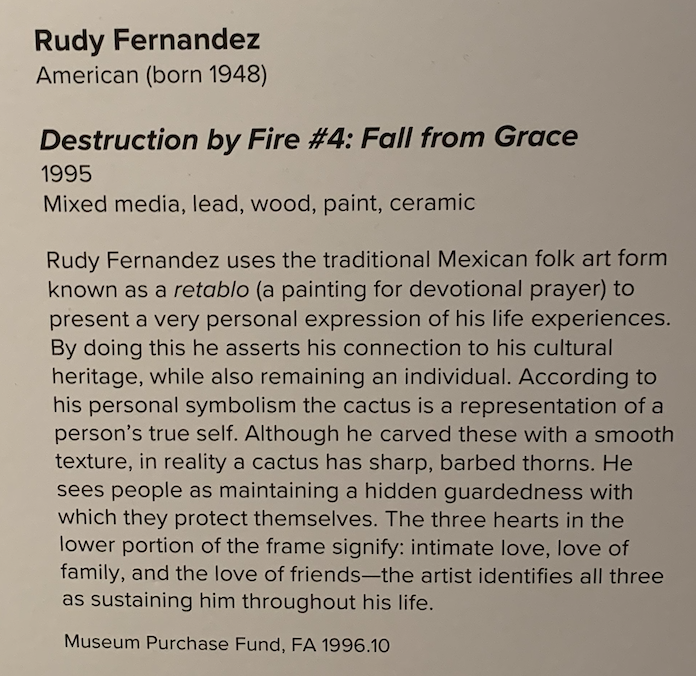

Vicente Telles, one of many artists whose work we looked at in class and the FAC, dismantles this idea of Indigenous art, culture, and identity as static, by illustrating the evolution of tradition, rather than its mere continuation or even disappearance. As a New Mexican Santero, Telles utilizes elements of Christian folk art, which is characterized by religious imagery, cosmic symbols, subdued color palettes, asymmetry, and frequent absences of naturalism and depth. He maintains this iconic New Mexican style and honors traditional artistic processes, while incorporating modern aesthetics and subjects. For example, in his 2020 painting entitled Madrecita, a modern twist on a traditional retablo, Telles depicts a Latina woman with beautiful braids, modern clothing, and a hardened, almost despondent facial expression. She looks forward, her head enclosed by a wooden cell covered in barbed wire and wilting flowers. Although just a woman, her facial expression and body positioning mirror that of a saint, a santo. Telles’ use of Christian iconography to emphasize culture and identity rather than religion, and to introduce pervasive issues, like immigration detention, border crossing, violence against Indigenous women, and the “flattening” of Latinx, Chicanx, and Indigenous identity may appear anachronistic. However, it effectively encourages viewers to assess and analyze the seemingly dichotomous motifs of tradition and modernity, pushing them to see the connection between and converging of the two. Ultimately, Telles employs a contemporary lens to advance the Santero tradition to make it relevant, illustrating how his individual and collective New Mexican identities are constructed by the incorporation and evolution of tradition into the present-day.

Exposure to both Telles’ traditional and contemporary works brought to light the concurrent evolution and liberation of Southwestern culture and identity, with the development of colonialism into the modern white power structures and supremacy that are implicated through Telles’ artistic commentary on societal issues affecting Indigenous peoples. The evolution of the past into the present shown in his art afforded me the understanding of how arbitrary the division between labels of traditional and contemporary is, and why Southwest art and culture should not be defined by colonialism, conquest, or current Western perceptions of Indigeneity.

All the art we looked at this week was created with the idea of evolving tradition in mind. This art, in conjunction with class discussions, assigned readings, and guest speaker visits, illuminated how art can be used as a tool for decolonization and resistance. Furthermore, as I grew more informed, my perspective on and gratitude for Southwestern art changed and grew immensely. Appreciating this genre of art aesthetically was immediate but being able to think critically about New Mexican history, Indigenous practices, different power structures, and the influence of the past on the present took more time.

Altogether, I am very thankful for the opportunities I had this week to engage with my peers, guest speakers, and others who contributed to our class. After taking six consecutive STEM blocks, I began feeling like my education was becoming a process of memorizing information and regurgitating it on exams. It felt mechanical. I registered for this class with the intention of taking a break from STEM and meeting two general education requirements but have already gained far more than that. This block is just my second of two fully in-person blocks I have taken at CC, and it has yet to disappoint. I experienced my first trip to the FAC, in-person discussions with both peers and guest speakers, creative assignments, and much more; content from some of my favorite moments from this week is included below. I am very excited to see what is in store for the coming two and a half weeks!

Miles Tokunow’s creative performance project we watched for class, “Stages of Tectonic Blackness” https://vimeo.com/466734530 (3 minute version), https://vimeo.com/489564928 (27 minute version)