By Ella Reese-Clauson ’26, International Political Economy

On the first Friday of COP29, I entered the generally professional and sterile Blue Zone to the sight of a small line of business-clad delegates waiting to have their picture taken with a pair of attendees dressed in inflatable polar bear suits. One after another, the delegates excitedly posed with the polar bears, complying obediently when the photographer told them to “say cheese for nuclear energy.” One of the bears’ peers—dressed in a bright blue T-Shirt plastered with pro-nuclear energy slogans—handed out bananas, smiling as he professed that living next to a nuclear power plant for a one year period exposed you to the same amount of radiation as a single banana. His thesis? If we’re not scared of bananas, we shouldn’t be afraid of nuclear energy. The man, a nuclear engineer from the UK, passed me a bruising brown banana that was perhaps not the happy, healthy image he was going for. When I asked him where I could find this report, he told me to look on the website of any power plant. Clearly, their sources were unbiased.

The organizers were affiliated with Nuclear for Climate, an observing delegation linked to British, French, and American Nuclear Societies that had stood out all week in their signature blue T-shirts.

The action was in the perfect location at the entrance hall to the Blue Zone. Every delegate who entered that day walked by, swarms and swarms of people headed to their morning constituency meetings and party office spaces. As I stood to the side of the now-dancing polar bears, furiously jotting down notes and checking my schedule to see when my first session was, I heard a man complain that the organizers were “spreading all this health disinformation.” The desperate ethnographer I am, I beelined for the man, introducing myself and making small talk before getting to the meat of my questions. His name is Tim Judson and he’s the executive director of US-based Nuclear Information and Resource Service. He furiously told me that this comparison of nuclear energy exposure to a banana’s latent radiation was a recycled and debunked claim from the 1950’s. He said that, in the 50’s, nuclear energy companies wanted to dispel fears related to nuclear energy and detach it from nuclear weaponry in American minds, so they skewed some numbers to create the claim Nuclear for Climate was using today. My quick Google search later produced varying answers that could not confirm or deny his claims about the argument being debunked.

A Danish woman joined our conversation briefly, complaining that “all these Africans and Asians are seeing this and thinking it’s a good idea.” She pointed back to the crowd, where a group of Chinese delegates posed with the polar bears, holding a pocket-sized Chinese flag and chiming “China for nuclear.” She huffed away towards the meeting rooms and Judson continued his spiel, lamenting that Nuclear for Climate had somehow obtained the most highly sought-after “advocacy action” location at the most highly sought after time period every day of the coming week.

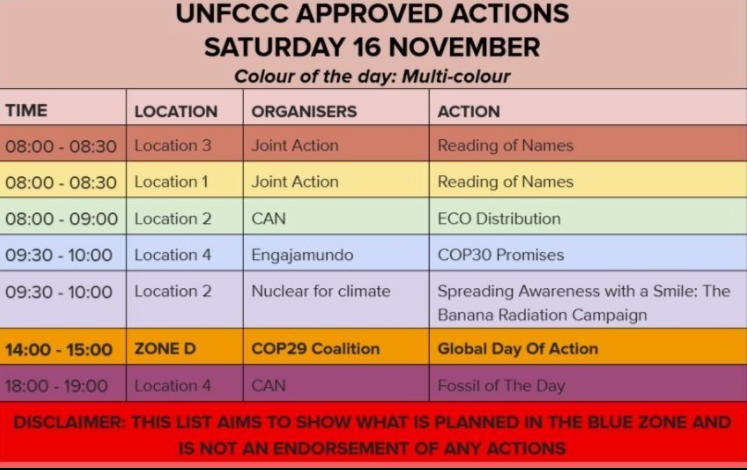

For some context into the bureaucratic nature of activism at COP, all actions have to be approved the day prior through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Chage (UNFCCC) secretariat. Even those approved actions are heavily regulated, with secretariat representatives deployed at all actions and members of the host country’s law enforcement fencing organizers into designated action locations with retractable belt barriers. The secretariat offers limited times and spaces, necessitating an in-depth application and censoring certain words. Nuclear for Climate had clearly lucked out with their bids.

Earlier in the week, I had been added to a group chat of nearly 550 young delegates dedicated to planning actions at COP29. The group chat is generally a friendly space where people plan movements, send relevant articles, send the day’s schedule of approved actions, and occasionally coordinate evening social events and parties. That Friday night after Nuclear for Climate’s action, however, the atmosphere became tense. The schedule for Saturday’s planned actions dropped, this time with a disclaimer at the bottom stating that the list “is not an endorsement of any actions.” On the list was the sequel to the morning’s polar bear photoshoot, an event entitled “Spreading Awareness with a Smile: The Banana Radiation Campaign.”

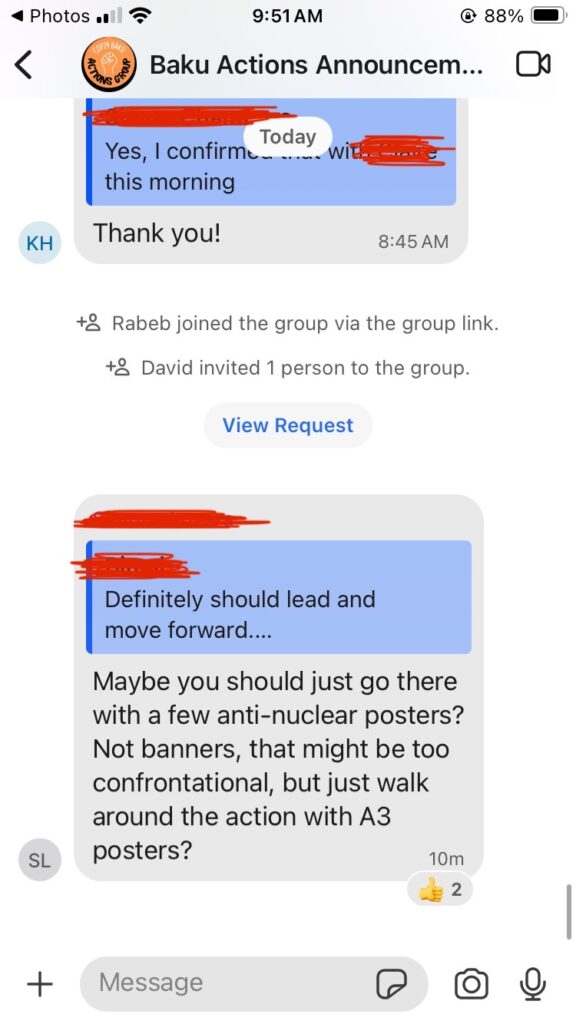

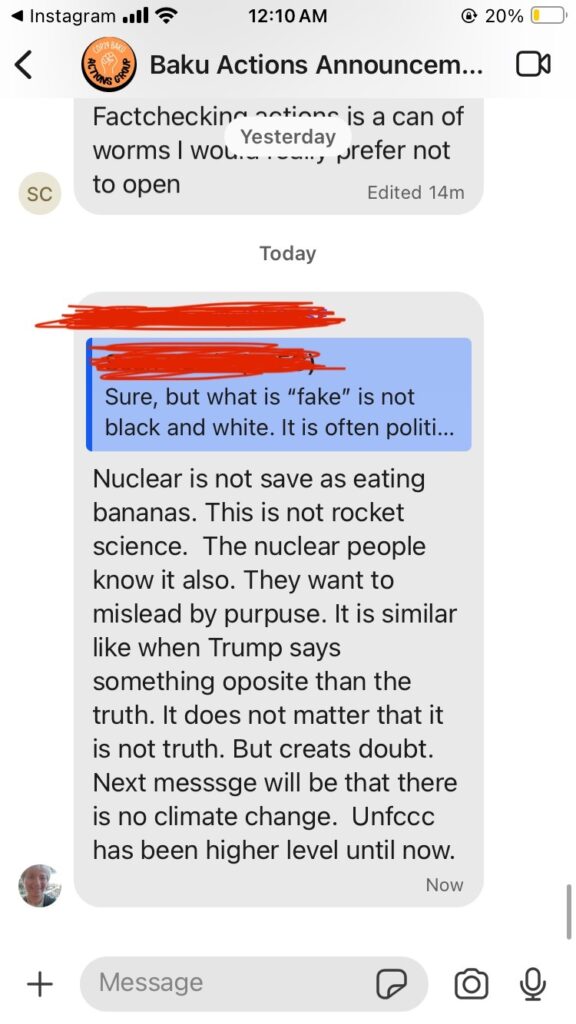

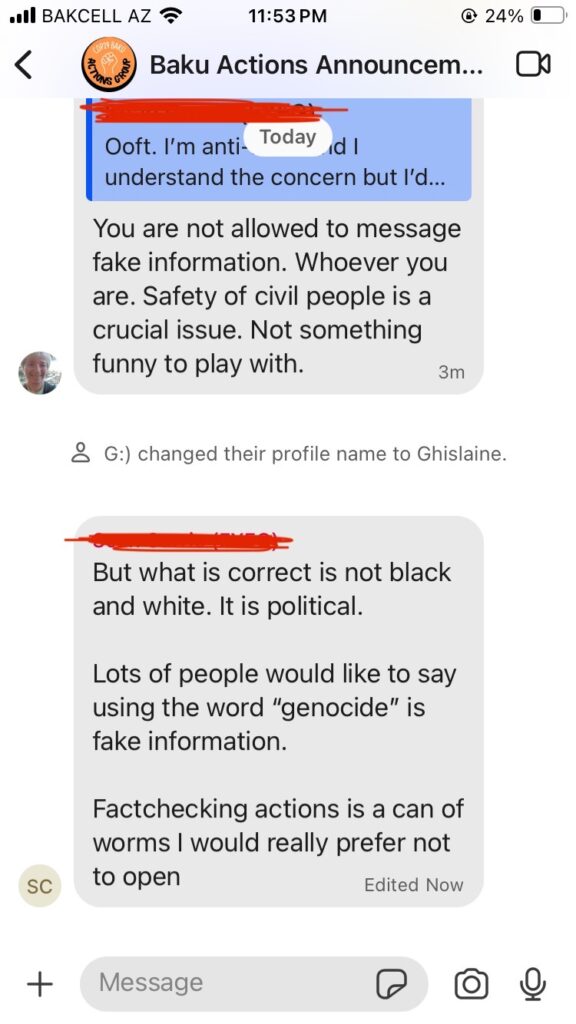

The message sparked immediate backlash from delegates who echoed Tim Judson’s comments, labelling the Banana Radiation Campaign as dangerous public health misinformation. Heatedly, members argued about whether it was appropriate to file a complaint with the secretariat. Those in favor of a complaint boldly compared Nuclear for Climate’s words to Donald Trump’s disinformation tactics, while those against it warned that doing so could prompt heavier censorship from the secretariat. Though pro-nuclear messages were ultimately deleted from the chat, prompting questions of censorship in the very space organizing against such suppression, the protest proceeded as planned for the rest of the week.

On Monday, I stopped by the retaliatory “Climate Justice Demands Real Solutions, not False Promises: Oppose the Pledge for Global Nuclear Expansion” action organized by Tim Judson’s very own Nuclear Information and Resource Services organization. The action was further into the Blue Zone, nestled near the plenary halls.

The protest was captivating. Being placed outside meeting rooms, the Secretariat representative on hand claimed they had allowed the action under the condition that it be silent. The group, who had been initially told it was a low-volume but not silent action, stuck with their original impressions. They alternately hummed, snapped, chanted, and sang South African resistance songs, holding out their palms toward the crowd in a silent plea to stop and wielding signs reading “Don’t Nuke the Climate,” “Solutions are not radioactive,” and “nuclear free and carbon free.” The group was diverse, heralding from South Africa, the UK, Australia, Nigeria, Germany, and the United States. They rallied around three main cries: too dangerous, too expensive, and too slow. To them, nuclear energy had too many dangers—both nuclear waste and nuclear weaponry—and the infrastructure required for the transition would take too much time and money to create the necessary infrastructure.

I spoke with Karina Lester, an Australian second-generation nuclear testing survivor badged with the Australian Confederation Foundation. Dressed in a bright yellow T-shirt with a QR code to a “Nuclear-Free Future is Possible” website, she informed me that the group had been at every COP since COP6 and had rallied multiple NGO’s from all over the world against nuclear energy. She pointed out, in rapid succession, all of the people in the demonstration, listing their stories, names, origins, and accomplishments while highlighting the many international environmental awards members of the group had received. She modestly failed to mention that her own organization, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

As the protesters broke out into an English-translated rendition of the South African protest song, “My Mother,” she handed me a pamphlet for ICAN Australia. It explained that, from 1952 to 1963, the British and Australian governments conducted “12 major nuclear test explosions and up to 600 so-called ‘minor trials’ in the South Australian outback and off the coast of Western Australia.” The tests dispersed “24.4 kg of plutonium…, 101 kg of beryllium…, and 8 tonnes of uranium” that impacted not just the more than 16,000 test site workers but also the nearby Indigenous communities who “have borne the brunt of this ongoing scourge.” The pamphlet walks through the health impacts of this weapons testing and its legal precedence before spotlighting a few first-hand experiences, Lester’s included.

As I read about the tragedy-ridden stories of these activists, the protestors in front of me whisper-sung:

My mother was a kitchen girl

My father was a garden boy

That’s why I’m an activist.

I entered COP with perhaps embarrassingly little knowledge of nuclear energy, but I certainly found this action more compelling than the heavily scripted Banana Smile Campaign. Notably, however, the pamphlet and the conversations I had at the anti-nuclear action focused on nuclear weapons rather than nuclear energy; for them, the development of nuclear weapons was an innevitable consequence of nuclear energy. Their argument against the energy source hinged around this conclusion. Nuclear for Climate members I had spoken with earlier that morning had condemned the development of nuclear weaponry but had not seen the two as inextricably linked, saying that they would “of course” organize against the development of weaponry but thought nuclear energy could develop without its violent counterpart.

Beyond the engagement of civil society in actions, the past two COPs have been overwhelmingly in support of nuclear power. COP28 was the first COP to include nuclear energy in its final decision, with parties concluding that the power source would have to play a key role in reaching net zero. In Dubai, 25 countries launched a Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy Capacity by 2050, concluding that they could not meet their respective Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) goals without nuclear energy. The prior week at COP29, six more countries had joined their ranks.

On the following Monday afternoon, I attended a side event titled “Tripling Nuclear Energy: How to turn Commitments into Action.” The room was sparsely populated, but I chose to sit between Judson and a Nuclear for Climate Member, each donning the T-shirts for their respective causes. Panelists, all of whom were associated with the nuclear energy sector, treated the transition to nuclear energy as a given and thoroughly answered question of how their respective countries would move forward both with their own nuclear energy goals and with supporting those of emerging economies. They addressed concerns about financing, the supply chain, and structural unemployment, treating nuclear’s benefits as a given. At the end, Judson notably held back his applause.

In the past week, the representatives of the United States have not been quiet about the nation’s plans to close in on nuclear energy as a primary clean energy solution. At a closed United States briefing from John Podesta on the United States’ priorities at COP29—which was largely overrun by questions about the election and whether President Biden plans to submit a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) plan before the end of his term—Podesta noted that nuclear energy has bipartisan support and will move forward towards the tripling goal in the United States. Similarly, in a press conference on Saturday, members of the US House of Representatives praised nuclear energy for its national security and energy potential. Just last week, the US roadmapped a commitment to 35 increased gigawatts by 2035 and an eventual 200 GW target by 2050.

The debate over nuclear energy at COP29 reflects the duality of the event itself: one COP filled with civil society’s impassioned discussions and actions, and another with party delegates negotiating behind closed doors. This year’s outcome reinforces that dynamic: Civil society in Baku may be divided on nuclear energy, but the COP29 final decision will read in favor of the radioactive energy and the United States and its 30 co-signers will continue on their nuclear-ridden path. Nuclear energy, COP29 confirmed, is here to stay.