By Jamie Harvie, ’25, Anthropology

Each year, the UNFCCC’s Conference of Parties (COP) accrues an international assemblage of world leaders and students, activists and NGOs, government officials and economists, and everyone in between. During this two-week event, these individuals and delegations – all with varying levels of power, capital, and social capital – become actors and audiences. They sit and speak in press conferences and negotiations, walk the mazes of pavilions and exhibits, and listen to the proclamations of presidents and prime ministers in the plenaries. Ostensibly, they’re to witness and participate in the international efforts fighting against climate change. However, that is only one aspect of how the space of COP is utilized.

The international power and clout concentrated here accord a valuable opportunity for the efforts of state and non-state actors to legitimize narratives around contested (inter-)national affairs. This is especially true for the host nation – as the city where COP-goers eat, sleep, and explore becomes an inescapable venue for nation-branding. At COP28 in Dubai, for example, participants were subject to an omnipresent performance of “green nationalism.” There, the language, physical structure, and agenda of events and spaces were tailor-fitted to a narrative of oil’s benevolent and prosperous heritage in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the possibilities of a sustainable, post-oil future. In so doing, they obscured the climatic harm of Emirati resource extraction and attempted to legitimize their authoritarian form of governance.

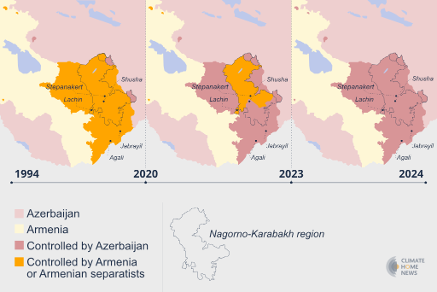

Azerbaijan, the UAE’s petro-state analogue in the Caucasus region, hosted 2024’s COP29 in its capital city of Baku. This year, one of the most common genres of narrative revolves around global conflict. Although there are any number of wars, skirmishes, and “special military operations” currently being waged across the world, there is one that was especially visible in the streets and venues of Baku – the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan. The space of COP29 became a symbolic flashpoint for this conflict, revealing strategies that state and non-state actors have employed to legitimize particular narratives.

Distinctions without a Difference

Back in March, I did not respond to the news that I had been selected as a member for Colorado College’s delegation to COP29 with an immediate and enthusiastic “yes.” Instead – paralyzed by hesitancy – I reacted by calling my mom, looking for her advice. Being unaware of the conflict in the Nagorno-Karabakh breakaway republic (NKR), she was confused by my reticence and discomfort with the idea of travelling to Azerbaijan. I tried my best to explain the historical struggles between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the predominantly-Armenian NKR, the 2020 and 2023 iterations of the conflict, the ethnic cleansing of Armenians in the region, and my fears that I would be helping to legitimize these abuses by attending COP.

However, I am writing this after having attended COP and living in Baku for over two weeks. I told (and tell) myself that the reason I was there was not for Baku or for Azerbaijan. Instead, it was because of COP. There was a distinction there, I told (and tell) myself. Yet each day that went by, I was greeted with challenges to that conceptual framework. Whether in the streets of Baku or the rooms and halls of the conference, it was difficult to disentangle the conflict from COP.

Finding Nagorno-Karabakh in the Halls of COP29

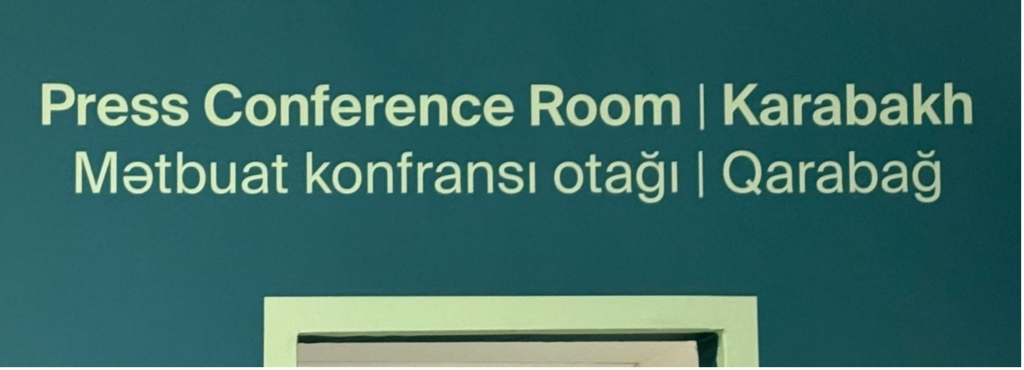

In Baku Stadium, the designated rooms where conferences and events are held owe their names to certain places, people, or symbols that are important to the history and culture of Azerbaijan – Buta (symbol), Shirvan (place), Natavan (person), Nasimi (person/place), Caspian (place), etc. However, Area D of the venue holds the most notable one – as that is where “Press Conference Room | Karabakh” can be found.

The significance of this particular toponymic decision should not be understated. The narrative-forming nature of place-naming and its relevance to nation-building processes is widely recognized in the academic world – even being the primary subject of analysis for the field of “critical toponymy.” Within this context, the ideological nature of this particular place-name would appear standard for a state production or performance of power.

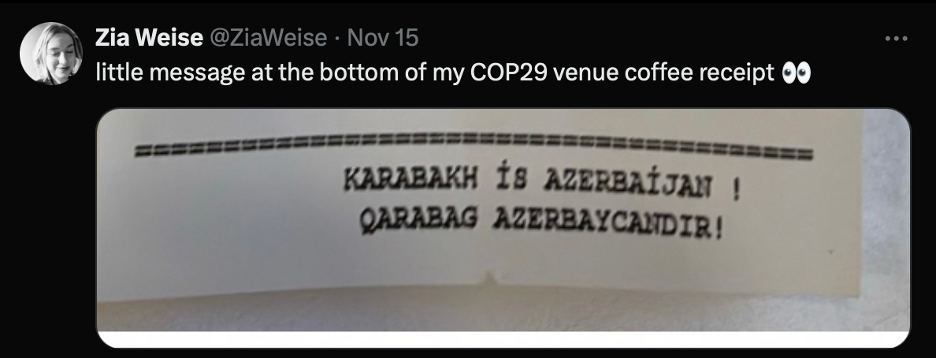

However, what makes the Karabakh conference room unique is its temporary existence in a place that is chiefly populated by non-Azerbaijanis, and which most Azerbaijanis will never enter. Therefore, it should not be seen as a material act of control over the actual place of Karabakh – that would manifest within place-naming processes in the region itself. Like the English message on the venue’s coffee shop receipts, this is not being done with Azerbaijani people in mind. Instead, it is a symbolic act that is meant to legitimize and normalize Azerbaijani control in the eyes of the venue’s attendants. It, like the receipts, serves as a constant reminder to this global audience that “Karabakh is Azerbaijani.”

From Spaces to Speeches

While the receipts and room names are certainly provocative, other attempts to legitimize and normalize Azerbaijani control over the region proved even more overt. Within the first 90 seconds of his opening speech at the World Leaders’ Summit, President Ilham Aliyev remarked on the “30-year-long occupation by Armenia” in Karabakh. Additionally, in trying to maintain relevance to the subject of climate change, he also used this time to champion the burgeoning green energy projects in the districts “liberated from Armenian occupation four years ago.”

What President Aliyev is referring to here is the region’s post-conflict recovery efforts centering around the establishment of green infrastructure and renewable energy sources. There, the rubble of the conflict is treated like a blank slate to ‘build back better.’ In fact, one Azerbaijani political scientist has go so far as to proclaim that, “Karabakh will be the new Silicon Valley, but in a green way.” However, other scholars, activists, and international officials have called these projects, and the rhetoric around them, acts of “greenwashing” that serve as a cover for ethnic cleansing.

Nevertheless, even when Karabakh is not mentioned by name, its centrality to the Azerbaijani agenda at COP29 remains evident. Sitting at the ‘Leaders’ Summit of the Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) on Climate Change,’ I awaited declarations from the leaders of these SIDS on the necessity to act quickly and forcefully on global emissions. To my surprise, however, the first person to take the stage for speeches was President Aliyev. The first half of his speech spoke to Azerbaijan’s financial and humanitarian support for SIDS and the need for powerful climate action on their behalf. Yet halfway through he switched subjects, shifting focus to the “neo-colonialism” of France and Netherland’s overseas ‘territories’ (read: colonies). Among other actions, he decried the carelessness and harm caused by their nuclear testing in French Polynesia and condemned the brutal repression of recent decolonial protests in New Caledonia.

In a vacuum, everything President Aliyev said about the continuation of French and Dutch colonialism is true and he would be right to bring it up. In fact, each condemnation was met with applause from Global South leaders and delegations. Even I found myself applauding at certain points. However, something felt off about his decision to speak on these issues, leading to many traded glances of perplexion with my classmate. In his final remarks in the speech, Aliyev alluded to his true intentions here:

But what else can we expect from the European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe if Chief European diplomat Josep Borrell calls Europe a garden and the rest of the world jungles?! If we are jungles, then stay away from us and don’t interfere in our affairs. (Emphasis added).

As it turns out, France is one of the most vocal opponents of Azerbaijan’s actions in Karabakh, issuing multiple condemnations and calls for sanctions. So – rather than statements born solely out of righteous indignation on behalf of those subject to colonial rule – Aliyev’s proclamations feel more like political posturing with the goal of delegitimizing France’s denouncement of Azerbaijan.

What’s Missing

Ultimately, what is just as – if not more – significant than what’s in the space or what’s been said in these halls, is what’s missing. Specifically, the Armenian delegation has been absent from this year’s COP. There had been a back and forth between the two nations in the months prior to the conference, with Armenia agreeing not to block Azerbaijan’s hosting privileges in exchange for the release of 32 POWs. Nevertheless, it was Azerbaijan’s refusal to release additional captives following this deal that determined Armenia’s decision not to attend.

It can be argued that in doing so they surrendered their ability to control the narrative around the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. However, such an argument would be a reductive reading of the situation. Rather, I believe that Armenia’s absence constitutes a form of what Andrew Donofrio calls “tactical silence.” Among those who chose to attend – me included – Armenia’s boycott is an act meant to “entice reflection,” as Donofrio puts it. We are meant to consider why we are here and they are not, and if that decision is something that can be justified.

As it stands, I am still grappling with those questions. This has not been the “COP of peace” that Azerbaijan tried to frame it as in the months preceding the conference. Rather, narratives around armed conflict permeated throughout the venue, laying bare one of the biggest hurdles to global cooperation on climate action: its inseparability from human rights and international justice.