Studying war has been a personal and professional passion of mine for many years. As a CC student, my independent minor focused on the war poetry emerging from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. At Dartmouth College for my Master’s, I published a paper on my grandfather’s experiences in World War II, and my thesis explored the wartime poetry of Wilfred Owen and Keith Douglas. Returning to my alma mater, I wanted to use a different, and timely, lens to explore the college’s history.

The Early Years

Founded in 1874, nine years after the end of the U.S. Civil War, Colorado College’s early years took place on the frontier of the American West. Colorado would not become a state until 1876, and so the first students and faculty of the college arrived in what was then know as the Territory of Colorado – established in 1861.

A state with a diverse and proud history, Colorado’s frontier was a place of danger and excitement. The territory, initially thought to be on the periphery of the predominantly East Coast-based Civil War, became a crucial battleground in 1862. The Confederate invasion of New Mexico that year was a prelude to the planned invasion of the Colorado Territory. The Confederate invasion of these regions hoped to cut supply lines from California to the rest of The Union. The Confederate forces were defeated at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, from March 26-28 of 1862, and their plans to cripple Union supply lines were thwarted.

Another, and equally crucial, conflict that made up the historical backdrop to Colorado College’s early years was the Colorado War. Brought West by the Colorado Gold Rush, the settling populations demanded that the U.S. government override the tribes claims to the lands, and without provocation they moved to force the tribes into a reservation by force. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux tribes fought against the settling miners and militia populations of the plains of Colorado, Wyoming, and Nebraska – largely for control over the bison migration grounds of the aforementioned lands.

Coming of age as an academic institution of some regional and national renown with the backdrop of the post-war American West, Colorado College has been imbued with a spirit of exploration and determined resolve ever since its early years. Despite its contemporary reputation as a bastion of liberal thought in the American West, CC has long had associations with the act of war and the institutions that carry it out.

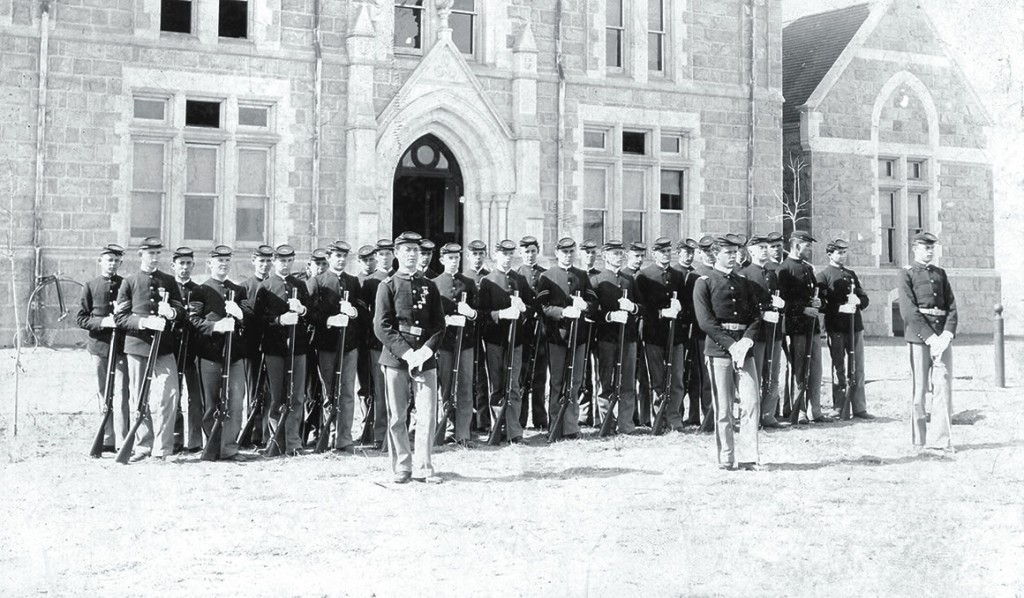

Gen. William Jackson Palmer, one of the early financial and land benefactors of Colorado College, was made a general during the Civil War and received the Medal of Honor. In the late 1880s, Colorado College began hosting the drill team of Cutler Academy. According to The Colorado Collegian, the precursor to later college news publications The Tiger and The Catalyst, the drills “commenced with real earnest, and it is a familiar sight to see the boys marching on the campus, responding to the stern orders of the commanders. Several more guns are needed […].”

A Century of Turmoil

In the 20th century’s early decades, Colorado College’s contribution to both global scholarship and global conflict grew. The United States’ entry into the Great War on April 6, 1917, “marked the beginning of an era of profound change in American society — a change in values and mores that would also bring turbulence to the college” (Juan J. Reid, “Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 85). On May 8, 1917, a special Commencement ceremony was held for those withdrawing for military service. Fourteen men, bound for the Army Reserve Training Corps at Fort Riley, Kansas., were awarded their diplomas that day. Additionally, the CC faculty lost three members to government service in connection to the new war efforts.

In January 1918, the college adopted a military training program for all male students and was tasked with the instruction of an Army Signal Corps service school. The first contingent of men, trained as radio operators by the college’s Physics Department, reported on May 15, 1918. Hagerman Hall and Cossitt Gymnasium were converted to military housing for the troops, Washburn Field was used as a drill field, and trenches were dug on the campus near Nevada Avenue to provide training in trench warfare. Straw-filled dummies were set up so that male students could practice bayoneting the enemy. (Robert D. Loevy, “Colorado College: A Place of Learning, 1874-1999,” Page 111)

For the remaining seven months of the war, a total of 512 men received radio and telegraph training at the school. Of those 512, “355 had seen service overseas” (“Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 89).

Under the assured leadership of CC President Thurston J. Davies, the college experienced drastic growth. New property acquisitions, and renovations to student housing, additional student services, and instructional improvements despite harsh economic times added to a seemingly unstoppable wave of optimism surrounding the college as the 1930s came to a close. With the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, Colorado College entered a new phase of military involvement — one of its most prominent and enduring.

As the Axis forces moved across Europe, the mood on campus began to change. CC students were polled about the possibility of the United States getting involved in the war, and it was shouted down — 290 to 20. Against. By the fall of 1940, however, the situation overseas had drastically changed. Britain was on the verge of collapse, and France had fallen under the rule of the Vichy government — a puppet government of the Nazis, who had taken control of the country.

The U.S. acted incrementally, first passing the Compulsory Military Training Act. At Colorado College, all male faculty and students between the ages of 21-35 were required to register for the draft. A year later, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, winning the war replaced educational excellence as CC’s primary goal. (“A Place of Learning,” Page 126). Male students began to disappear from campus as they either volunteered for or were drafted into service. In March 1942, President Davies was commissioned as a major in the U.S. Marines and assigned to Marine headquarters in Washington, D.C. His influence on Colorado College did not wane during his absence, as he was placed in charge of the Navy V-12 college training program. This was designed to enlist and train young males for military service while also allowing them to take college-level classes. Colorado College was quickly brought into the program.

Once again, Washburn Field became the focal point of all military drills and training on campus, and victory gardens were set up grow vegetables and raise livestock to help the war effort. While President Davies was in Washington with the Marine Corps, Dean Charlie B. Hershey was appointed as acting president of the college. He made swift changes to implement all the necessary requirements for the college to take part in the V-12 program. The college converted more than half a dozen buildings into Navy housing and erected Quonset huts and barracks on campus.

Quonset huts on campus, used to house enlisted students, families, and, after the war, veterans and returning students.

All told, 52 CC students lost their lives serving their country in the Second World War.

Throughout the course of the war, the city of Colorado Springs changed dramatically. Camp Carson, constructed in 1942, “became a major Army training base, particularly for tanks and other forms of mechanized warfare” (“A Place of Learning,” Page 129). Peterson Air Field, an Army Air Corps training base, was built to the east of the city, and the “headquarters of the Army 2nd Air Force was established in the eastern section of the town” (“Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 155). These additions brought thousands of servicemen, workmen, and families to the city. In short, Colorado Springs grew to resemble the town that later Colorado College graduates came to know – a military town.

After the war ended in the fall of 1945, Colorado College entered a period of prosperity and togetherness. President Davies returned to his post, but health concerns forced him to resign in 1948. Colorado College’s eighth president, William H. Gill, took over for him.

William H. Gill Military Postings and Honors:

• World War I: Served in Europe, awarded Silver Star for bravery.

• World War II: Oversaw both the 89th Infantry Division at Camp Carson and 32nd (Red Arrow) Infantry Division in the Pacific Theater. Awarded his second Silver Star, the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Legion of Merit, and Bronze Star.

Gill’s appointment came at a unique time in the college’s history. With four out of five male students being veterans, as well as several among the faculty, a man with military leadership experience was perhaps the best choice to take CC’s helm. By the late 1940s, the growing threat of communism had unsettled many in the federal government, particularly in the post-war fallout and confusion. There was, according to Loevy, “considerable concern that agents of the Soviet Union and their domestic sympathizers were trying to infiltrate educational institutions in the United States and preach a philosophy of world communist revolution” (“A Place of Learning,” Page 134).

In 1949, the House Un-American Activities Committee requested that 103 colleges across the country, including CC, send lists of their textbooks and readings used in social science and American literature classes. Gill replied to the request by saying, “Colorado College is a private, independent college. We are not about to send you or any other agency of the government the information that you requested concerning our textbooks and collateral readings” (quoted in “Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 169). After pushback from other colleges, the request was withdrawn nationally and the matter left to rest. The college moved forward under a newly deliberate leader with an eye toward the future — unhampered and unimpeded by litigation.

By the 1950s, the United States became embroiled once more in an international conflict, this time on the Korean peninsula with the outbreak of the Korean War. The CC community was impacted again, with all men — except veterans — required to register for the draft. An ROTC unit was activated on campus in the fall of 1952. Overwhelmingly, male students volunteered for the unit. Those who completed the four-year program received second lieutenant commissions in any one of the 15 branches of the U.S. Army.

The 1960s brought turmoil to American society at large, including Colorado College. There was, as Reid details, “a revolution in the morals and manners of college students developed on campuses throughout the country in the ’60s” (“Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 254). A counterculture of drugs and experimentation arose alongside growing military activity in Vietnam, and the frictions between these two factions grew into protests across the country and around the world. The draft added to CC students’ discontent in the mid-’60s, and organized protests erupted across campus. President Lloyd Worner was lenient to the concerns and political opinions of his students, allowing “any student who did not want to go to class to protest the war, or who wanted to speak out or demonstrate in opposition to the war” to do so freely and without hindrance (“Colorado College: The First Century, 1874-1974,” Page 183).

A New Century, New Wars

With the traumatic events of Sept. 11, 2001, the mindset of a nation — of the entire world — was irrevocably changed to a more wary and less assured one. The terrorist attacks in New York City, Shanksville, Pa., and Washington, D.C., killed almost 3,000 people. Despite being almost 2,000 miles away, the impact of these tragedies was felt deeply in the CC community. College staff was proactive in reaching out to the most affected students, helping them contact loved ones and arrange to visit families if necessary. Counselors were available for extended hours through the college’s Boettcher Health Center, and residential life staff organized meetings in the dormitories and residence halls so students could gather to discuss, debate, and engage with the issues that arose from 9/11.

Once the initial task of helping those students immediately affected had been underway for some time, the college felt that it was time to turn attention to the needs of the greater campus community. Classes continued, and different perspectives and opinions welcomed. There was also an “impromptu gathering” in Shove Chapel, allowing all members of the community to come together to share information, express their fears, and tell their differing perspectives on the events” (Loevy, “Colorado College: 1999-2012,” Page 19).

“Discussion and discourse […] is what we do,” President Kathryn Mohrman wrote in a letter to the CC community. She went on to say, “In times like this, a liberal arts education is more relevant than ever before” (“Colorado College: 1999-2012,” Page 19).

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the United States and its allies set in motion a series of conflicts that would come to define the first two decades of the new millennium. The global war on terrorism included two major conflicts and dozens of other smaller ones that have since emerged. The two major conflicts involving the United States were in Afghanistan, launched in 2001, and in Iraq — beginning with Operation Iraqi Freedom — in 2003.

As controversial as the Vietnam War in the ’60s and ’70s, the War on Terror propelled the CC community into a new era of heated debate and, occasionally, vocal disagreement. The author of this story arrived on campus as a first-year student in fall 2008, just as much of the initial activity was winding down.

That same sense of inclusion that President Mohrman wrote about is something that Jennifer Kerner ’07 touched upon in an interview conducted for this story, in which she discussed the perceived disparity between the military components local to the college and the college community itself. “Before we can discuss fostering acceptance and tolerance between two communities, we must be sure that we are employing inclusivity in our work, our lectures, and our discussions,” she said.

Kerner is completing her Ph.D. dissertation in political science at the University of New Mexico while working as the government liaison officer for the American Red Cross in New York City. The daughter of a volunteer physician in the Vietnam War, she traveled to Vietnam in 2006 with her father and cycled from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi.

“Perhaps the most difficult thing for me during my time at CC was the feeling that I had to play devil’s advocate for issues related to the military,” said Kerner. “The community I came from was fairly conservative with a solid military history, and my own family has a history of serving as well. I came to CC not knowing that such a divide could exist.”

Mike Shum ’07, now a filmmaker and video journalist, felt similarly. “There wasn’t so much aggression or anger as there was curiosity about these events,” he said. “My senior year roommate was one of my best friends from high school, then a helicopter pilot based at Fort Carson. I’ve always wanted to experience issues from the other side to what I know, and I’m never satisfied with one point of view — I always want more.”

“I think the perceived disparity comes from, not only a lack of understanding between the two communities, but a lack of desire to understand,” Kerner said. “Both communities may believe that they are the protagonist. And that’s where this false, I believe, divide arises. When I arrived at CC, I quickly learned from older students and by observation that my amicable relationships with USAFA (United States Air Force Academy) students were ‘un-Colorado College’ of me.”

A 2012 graduate — now working for the U.S. Army — who wished to remain anonymous for this piece, said that although CC “didn’t, for the most part, prepare me for what I do now,” it did “provide me the gift of mental endurance,” he said. He brings a unique perspective to the topic, one that is often overlooked in the larger narrative of the college and its relationship to warfare. “While CC in many ways did not prepare me for my job in the Army, it did prepare me for life […] and it is my hope that I can use both of these experiences together, rather than driving a wedge between them.”

Colorado Springs is a city, now more than ever, dominated by a military economic base. According to an article headlined “Discover: Economy Dominated by Defense” by Wayne Heilman in the Colorado Springs Gazette from Sept. 21, 2014, more “than 55,000 civilians and military personnel work for the Department of Defense at the Air Force Academy, Fort Carson, Peterson Air Force Base, and Schriever Air Force Base.” Additionally, Heilman wrote that an estimated one-fourth of economic activity in the Colorado Springs area is made up of “defense-related business and payrolls.”

In 2013, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, an estimated 53,575 veterans were living in Colorado Springs. With this population in mind, as well as the aforementioned economic base of the city, Colorado College has chosen to take a proactive approach to assisting those men and women who wish to pursue a CC education. Under the leadership of President Jill Tiefenthaler, CC now participates in the Veteran Administration’s (V.A.) GI Yellow Ribbon Program. This is designed to alleviate some or all of the costs of higher education for returning veterans. At the time of writing, the college offers financial assistance to five undergraduates and 10 MAT students — $32,077 and $28,007 respectively, per year.

These funds not only offer relief and opportunity to current veterans, but the college’s involvement in this program harkens to its historical commitment to serving its community and its country — not solely as a force for education and understanding, but also for issues of gravitas and great upheaval.