40 Years In, the Allure of Letterpress Remains

“This Press has always depended on the kindness and devotion of students who want to help make books. What better environment is there for a student in a liberal arts college? What more encourages a range of inquiry, teaches crafts which ask the mind to work to the limits of the hand and eye, demonstrates the intersection of disciplines, the flights and vagaries of process, the focus of affection and all kinds of gratifications?”

— Jim Trissel, professor of art and founder of The Press at Colorado College

The Press is a virtual museum of type and fonts with most walls providing a collection of fonts and sizes for students to choose from for their projects.

A bit over 40 years ago, Jim Trissel, a fine art painter and art professor at Colorado College, was enlisted to help transport an old press to campus and cajoled by the then-provost to make something of it.

Intrigued, and with the old Asbern cylinder and Chase platen presses installed, Trissel took a sabbatical from teaching art in 1977-78 to learn the technology, design, and history of printmaking, and later began to collect classic typefaces. The craft of fine letterpress printing had captured Trissel’s imagination. The Press at Colorado College was born.

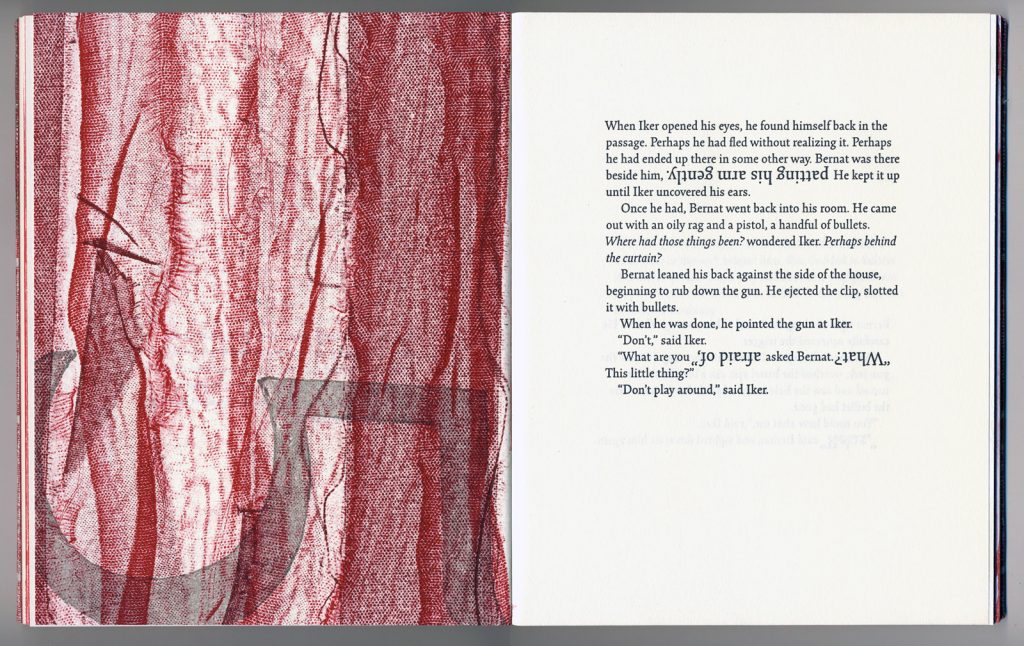

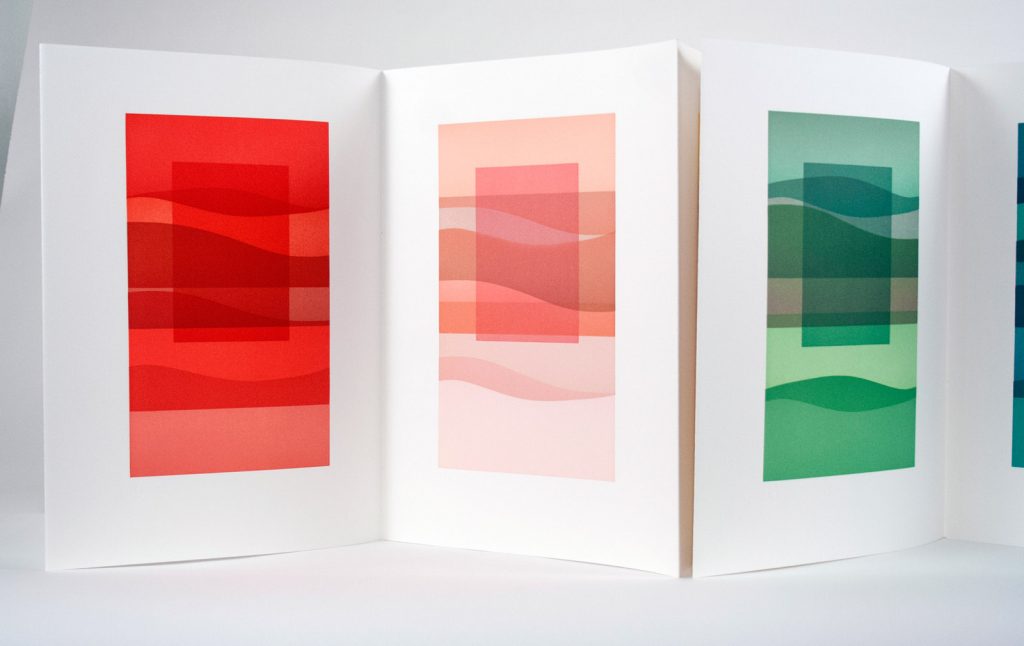

Two generations of CC students since have been lured by its creative nature — rolling ink on metal and wood type, fabricating vivid, handmade posters with chubby, graphic typefaces or spare, elegant volumes of poetry.

Over the years, The Press has produced many superb works of art that are featured in collections at the likes of Yale University, Harvard University, Chicago’s Newberry Library, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Now housed in Taylor Hall, The Press has published notable books including a book produced on commission from the Arts for Nature Trust of England as a 75th birthday gift for Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh; several books collected by the Newberry Library in Chicago; and three publications included in the New York Public Library exhibits “Seventy from the Seventies,” “Eighty from the Eighties,” and “Ninety from the Nineties.”

Trissel died in 1999, but The Press lives on.

Letterpress is the process of ‘relief’ printing using a press and movable type where a reversed and raised surface is inked and then pressed into paper to obtain an image.

Following a revival that began in the 1960s led by various design schools and The Press at CC re-introducing the teaching of letterpress, the previously specialist and expensive form of printing has become more widely used and appreciated once again.

When The Press’s current printer Aaron Cohick came to CC in the 2010-11 academic year, he was charged with rebuilding the curriculum and publication program — tweaking what existed and making it stronger. He sees The Press as an interdisciplinary, imaginative, and creative enterprise. And he’s tried to make it a welcoming space.

“I try to see to the making of as much stuff as possible. Open the doors wide. Get as many students in here as we can,” says Cohick.

“I try to see to the making of as much stuff as possible. Open the doors wide. Get as many students in here as we can,” says Cohick.

He sees The Press as a complement to academics on the Block Plan. Any class at CC can come in and do a project of their choosing; Cohick will work with the professor to see how letterpress printing can augment their class. But, in addition, he sees The Press as a place of respite or refuge.

The Block Plan can feel frenzied, noisy, chaotic at times. And, surprisingly, for a place with a lot of moving metal parts and hard surfaces, The Press is not those things. Instead, it’s an often quiet, reflective space. Labor is required, but at a slower, more meditative pace. There can be attention to long-lasting projects.

The Press also has become a place to gather as a community to work on activism-related projects.

The day following the 2016 presidential election, Cohick wanted to bring people on campus together to process their emotions and build community. “The Work Continues” poster project came out of that desire. Cohick designed the framework, put out a call to students, and encouraged people to come by The Press and make some art. About 15 students, “some who had never been here before,” and an assortment of staff, faculty, and local alumni visited The Press, chose the phrases that would go along with “The Work Continues” concept, and helped print.

“We gave away 700 in the first three days,” he says, and, to date, they’ve printed more than 1,900 copies of the posters that spread messages such as “Stay Kind,” “Stay Strong,” and “Stay Fierce.” “The Work Continues” project spread from the CC campus, and posters showed up at women’s marches across the country (including one CC parent who marched with hers in Washington, D.C.)

The Press runs two classes per year. Book and Book Structure is taught by a rotating roster of visiting artists. Cohick often teaches the Book Arts and Letterpress class. Since Trissel’s time, The Press has even had a pseudo commercial poster printing operation; people can order posters and the printing gets assigned to students based on interest and availability.

Longer-term book projects can take up to two years to complete. “There’s always some sort of big project underway that I try to involve students in. Or, students might have their own idea for a poster or a zine for a group they’re in,” Cohick says.

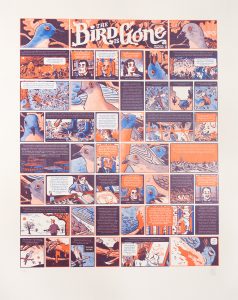

The projects undertaken by The Press are diverse, Cohick says: Three broadsides for the Indigenous Reading Series, several full-length poetry books, a comic broadside about the extinction of the passenger pigeon, for example.

Aaron Cohick shows First Year Experience students Isabel Hicks ’22 and Sarah Burnham ’22 how to line up the paper on the press before running it through. The students were working on a book arts project.

Who is the audience for these items?

“Ideally, the audience is everyone,” Cohick says. “Broadsides, posters, and prints are inexpensive; good for anyone who would like some art to hang on their walls. People interested in contemporary art, literature, poetry, printmaking — all are audiences for letterpress items. For limited edition books, audience becomes trickier. They’re expensive for books, but cheap for art. For those, libraries are buyers, private collectors, other institutions that have teaching programs.”

As to the ‘why’ … why do letterpress printing at all at a place like CC?

“I’ll tell you what The Press is not. It’s not about a living history exhibit. It’s not even about preserving history,” says Cohick. “It’s more about how these processes can redirect our attention — how it changes the way you look at a printed page, makes us slow down, focuses our attention in different ways. It’s about the doing and what comes out of that. Getting your hands dirty, making mistakes.”