It’s Spring 2020, and Colorado College’s campus is mostly empty, with students’ finishing their classes online because of the global fight against COVID–19. A century ago, the college was fighting a different global pandemic, and now some are returning to the archives to learn about it.

“Here we are in April of 2020, undergoing a global pandemic, with Colorado College students distance-learning, and CC faculty and staff mostly working from home,” wrote Jessy Randall, archivist and curator of Special Collections, in a blog post. “Naturally, I’ve been getting some questions (via email) about the closest thing we have to a parallel situation in CC’s history, the 1918 flu pandemic.”

In April 1917, the U.S. entered into World War I, and in January 1918, CC began to host an Army Signal Corps service school, a military program that trained men to be radio operators. Later that year, a pandemic sometimes referred to as the “Spanish influenza” swept across the globe, infecting around 500 million people according to estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and thus altering the structures of higher-education institutions like CC.

One of the earliest mentions of the pandemic in The Tiger, the CC student newspaper now named The Catalyst, came in an Oct. 1, 1918 article about the football team.

“Work was hindered somewhat last week by the precautions taken against a possible outbreak of the Spanish influenza, but now that all danger is past, the practice will be even more energetic than before,” the paper wrote.

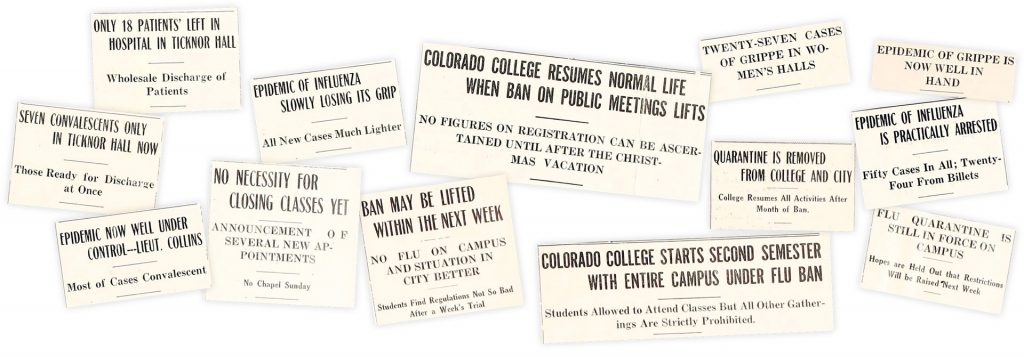

Three days later, the newspaper reported that the outbreak was “well under control.” Later that same day, CC canceled classes in accordance with a city ban on all public meetings. Ticknor Hall became an emergency hospital largely staffed by members of the local American Red Cross chapter, and Montgomery Hall became a convalescent ward. The paper reported that headaches, vomiting, bloodshot eyes, and a fever of 100 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit were some of the influenza’s early symptoms and warned students to report “even the slightest cold” immediately.

“The advice is basically the same 100 years ago and today,” Randall says. “Wash your hands. Don’t get too close to people. Don’t cough on people. If you feel sick, don’t go to class.”

Over the course of the next month, there were an estimated 180 cases of influenza at CC. Eight men in the Army radio school and Physics Professor William W. Crawford died from the influenza.

By Oct. 29, only seven patients were left in Ticknor, and classes resumed on Dec. 16 after the city lifted its ban on public gatherings.

“In order to go to Colorado College, everybody had to get on the campus,” said Fern Pring Corley 1922 in an archived interview with Judy Finley ’58. “We couldn’t then leave at all.”

Over a year later, in January 1920, the influenza returned. Though the city’s board of health banned all public gatherings again, they allowed CC students to attend classes, as long as no other gatherings were held and students remained solely on campus. About a month later, the city removed the ban, and CC resumed its normal activities.

“It passed, we largely forgot about it, [and] we didn’t take the public health lessons from it that we should’ve taken,” said Metropolitan State University of Denver professor Stephen Leonard in a recent streaming panel hosted by the Denver Project for Humanistic Inquiry. “So the 1918 to 1919 flu largely faded from memory.”

Fast-forward to the fall of 1957, and the college was facing another influenza pandemic.

On Oct. 18, 1957, The Tiger reported that the weekly incidence of respiratory infections in the college infirmary had grown from 30% to 60% above normal over the past three weeks, and they were still rising. The pandemic was putting a heavy strain on the infirmary, and the paper reported that some cases may soon be cared for in the dormitories. A new vaccine had just become available, and the paper directed students to receive their shots at the infirmary for a charge of 50 cents.

At the time, Ann Latimer ’60 was a sophomore living in Loomis Hall. She says that women who were ill were held in their dorms, and since many men lived off campus, they used the infirmaries. She never got sick, but Latimer says she remembers at least 12-14 people on her floor of Loomis did.

“We just talked to them from the doorway while they were in bed,” Latimer says. “There’s nothing to do with masks or anything else like that — you just stayed a distance away.”

The peak of the 1957 outbreak for CC was around Homecoming in early November, when over 50 students were sick and missed the events, according to The Tiger. Shortly after, the influenza started to decline. No quarantine was necessary, and no members of the CC community died, Randall says.

“People were recovering at different times … but they weren’t reinfecting each other like this virus,” Latimer says. “So that came and went, and then life returned to normal.”

Though she says the flu outbreak in 1957 was different from the 1918 pandemic or COVID-19, Randall says it surprises her to see how similar today’s narrative is to the narrative 100 years ago.

“There’s no other way to get at history than what’s written down and what’s remembered, so it can be a comfort — it can be the opposite of a comfort — to see how similar things were 100 years ago,” Randall says.