CC’s Block Plan Celebrates 50 Years, and Counting

The origin of the Block Plan is typically told in the manner of a promising joke, the kind you know will take a while to unfold, but whose punch line is worth the wait.

Three professors walk into a bar.

The bar was Murphy’s, a dive on the north end of Colorado Springs. It was 1968, a gray and gloomy November afternoon, ahead of the regular happy hour crowd. The three Colorado College faculty members sipping beer in a booth were Psychology Professor Don Shearn and Political Science Professors Tim Fuller and Glenn Brooks.

A few months earlier, Brooks had been tapped by CC President Lew Worner to head up a comprehensive campus self-study as a preamble to the college’s 1974 centennial.

“The reason we had gone there was to discuss what we thought we had learned from that undertaking,” Fuller recalls. “It was a casual conversation, kind of a bull session.”

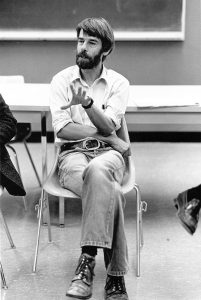

History Professor William R. Hochman displays his enthusiasm for a point made during class at Colorado College. Photo by Ben Benschneider

Talk inevitably turned to a persistent complaint. “What the self-study produced was a certain kind of agreement among all the different elements on the campus that their time was fragmented. People were being asked to devote themselves to a lot of different things at the same time,” Fuller says. “So we talked about this notion of fragmentation of time and energy.”

In those days, a conventional semester schedule had everyone juggling multiple classes simultaneously. Introductory courses might have a hundred students. And even “small” classes — say, 40 students — typically met for only 50 minutes three times a week.

“I was really getting frustrated with class size,” Shearn recalls. “And I wanted to have students have a discussion, and continue that discussion. That’s what prompted the remark at Murphy’s: ‘Why don’t you just give me 15 students and let me work with them? No bells; no interruptions.’”

Not a punchline, but a “eureka moment” in the development of short, intensive blocks in which students and faculty devote themselves to single subjects in succession, says Associate Professor Steve Hayward. The English Department chair is creating podcasts and a film, and overseeing publication of books commemorating the Block Plan’s 50th anniversary this year — officially, Labor Day.

It’s been a pressing and sometimes poignant task, as participants in the creation of the college’s most distinguishing feature disappear into history.

“We’ve been working on it two and a half to three years,” Hayward says. “We had to get it off the ground really early; we were aware that many of the people we needed to talk to were in fragile health, and we could miss them.

“And we did miss some.”

Economics Professor Emeritus Ray O. Werner died in March 2018. An effective, articulate critic of the plan, Werner is remembered as one of several opponents who — feeling the discussion was fairly and fully made — moved to implement the Block Plan immediately after faculty formally approved it.

History Professor Emeritus Bill Hochman, who memorably described the Block Plan as “playing a series of sudden-death overtime periods one right after another,” died in March 2019. And, at 89, Brooks — whose visionary leadership made the plan a reality — has lost much of his eyesight to macular degeneration.

They’re part of a generation of faculty that came of age during the tumult of the ’60s, a time of cultural ferment — and openness.

“It was a period of considerable upheaval in the country, with the counterculture movements, conflict over Vietnam, and civil rights … and also, it was an era of interest in experimentation in educational reform,” Fuller says.

The Block Plan “probably couldn’t have happened, and happened so fast, if it had not been the late 1960s,” Brooks recalls in an oral history of the plan. “The culture of the time was very much in favor of change in education.”

It was that spirit of openness and innovation, rather than discontent, that spurred the campus-wide reflection that birthed the Block Plan. A number of faculty, notably the late Political Science Professor Fred Sondermann, encouraged Worner to use CC’s centennial as an occasion for reflection as well as celebration. “[They] went to the president and said, ‘As we approach the centennial we should not just celebrate, but we should say what we plan to do in the second century,’” Fuller recalls.

Brooks took it from there.

“I proposed that, instead of setting up a committee, the college should operate more like a committee of the whole. The faculty should get as many people involved as it could,” he recalls. “A lot of that was pretty innocent, I suppose. I wanted this populist approach to changing the college — and to reflection about the college.”

Brooks “had this broad conversation with the faculty around the question, ‘How can we do what we do better?’” says History Professor Susan Ashley, whose book, “The Block Plan: An Unrehearsed Educational Venture,” will be published in conjunction with the anniversary. “It was a very good question. It allowed them to really think of something completely new without untethering from their mooring.”

One obstacle quickly became apparent.

“People felt pulled apart by the conventional semester system,” Brooks recalls. “They were jumping from one place to another and doing too many things. There developed a fairly quick — I won’t call it a consensus — but a dominant point of view: There ought to be a better way to organize ourselves.”

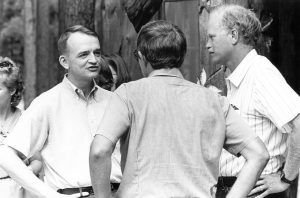

Political Science Professor Glenn Brooks discusses the new Colorado College Plan. Photo by Ben Benschneider

By early 1969, that “better way” began to look like the answer to Shearn’s frustrated question during that catalyzing conversation at Murphy’s: intensive blocks in which faculty and small groups of students could focus on a single course.

During the summer that followed, Brooks engaged the campus community with detailed memos that encouraged reflection on three crucial questions, Ashley says: “Could we do it, should we do it, and if we were to do it, how would we do it?”

And the whole thing began to seem possible. “I wouldn’t have given it a nickel’s worth of chance when I made that comment at Murphy’s,” Shearn says. “But when I saw Glenn Brooks working — he’s a very thorough guy, he listens well — and as the weeks went on, I thought, ‘This could really happen.’”

“Don had the original idea,” says Brooks, who emphasizes a team effort in bringing it to fruition. “My part was to add some structure to it and figure out how to make something like that work. The underlying principle was a group of students signed up to work with one professor full-time, where the professor would have pretty much full control.”

Opposition centered on concern that single blocks were too short for students to digest, reflect, and embed knowledge.

“It was only three weeks, and then students moved on to another course,” says Philosophy Professor Emerita Jane Cauvel, one of five influential senior faculty members who endorsed a hybrid plan for classes shorter than semesters but longer than blocks. “I felt they would lose a lot of what they learned in one block when they moved on to the next.”

As the alternative was developed and vetted, the Academic Programs Committee modified Brooks’ original proposal for 10 three-week blocks to nine 3.5-week blocks with a block break. It was that plan that 58% of faculty approved on Oct. 27, 1969.

What had seemed a pie-in-the-sky notion nearly a year earlier had become the college’s radical re-commitment to its central mission: providing a top-flight liberal arts education. Brooks again took the lead in making it reality.

“They had to find 100 rooms in which to have classes all at once,” Hayward says. “At other universities you can use the same room for three classes a day. At CC it’s thought of as a ‘course room’ that you can inhabit for the duration, this revolutionary idea of a classroom as a space to be made, not a space that exists. The Block Plan is a way of taking control of time — that’s how Glenn Brooks talks about it.”

Shearn claimed an attic room in Palmer Hall, a floor above his office. “[Brooks] wanted every faculty member to have a course room so you could be in there all day and not be interrupted,” Shearn says. “I put some couches in there, a coffeemaker, doughnuts. This was a 24-hour-a-day place; the door was always open.

“I could get up there at 7 in the morning and students would be in there talking. I built a self-instruction neuroanatomy program on 35mm slides. They’d be punching the buttons, looking at pictures, memorizing names.”

The plan was ideally suited to field trips. Shearn recalls taking students to a winter conference on brain research in Vail, Colorado, where a student’s family provided lodging. “They would intensively research one presenter in advance, and then talk with these presenters [at the conference]. It was a shock to these guys how much these kids knew.”

That kind of single-minded focus “put an end to what we call time-stealing, in which individual students had to make decisions about neglecting some courses in favor of more demanding ones,” Brooks says. Attendance quickly improved, because every day counted for so much, Fuller says.

The approach suited Lorna Lynn ’80, now an internal medicine physician in Philadelphia. Her daughter, Anna Lynn-Palevsky ’18, who recently earned a master’s in epidemiology from Harvard, also graduated from CC, and her son, Jacob Lynn-Palevsky ’22, is currently enrolled.

“The Block Plan allows you to be really immersed in a subject, so you start to think in that discipline,” Lynn says. “I remember my first course was physics. I was riding my bike up Uintah Street to get some things from King Soopers and I found myself thinking about gravity and acceleration, and I thought, ‘Wow, I’m thinking about physics while I’m riding my bike.’

“And that happened in most classes. It’s the immersion and the discipline that allows you to really understand different ways of looking at the world, and the small class size that allowed professors to really get to know their students, and to see who had a particular promise that should be nurtured.”

Nelson Hunt ’71 benefited from the plan, too, though it meant he would have to shift from a semester schedule to the Block Plan for his final year. “It looked worth trying,” he recalls. “I just wasn’t sure I wanted to be the guinea pig for that particular year.” The schedule ended up curing his procrastination, improving his GPA and embedding a skill he needed for the legal career he envisioned.

Political Science Professor Tim Fuller and Dean Dick Storey talking with a third person, back to camera.

“It did what I really wanted it to do in the real world — made me able to organize, plan, and write quickly, clearly, and well,” he says. “That was a skill I was able to develop throughout my entire career at CC, but particularly that senior year.”

But the Block Plan also created an unanticipated problem when Hunt applied to law schools — admissions offices that didn’t know what to make of his transcript. His first round of applications went nowhere. Four years later, after serving in the Coast Guard and then re-taking the LSAT — and after CC’s approach was better-known — he was accepted into law school, the beginning of a long career as a Washington attorney, prosecutor, and judge.

The plan was likewise both boon and burden to faculty in the early years, taxing some disciplines more than others.

“For some of my colleagues, it was a setback,” Brooks concedes. “To some extent in mathematics, but probably more in foreign languages. It was very intense.”

Some “poured old wine into the new bottles,” he says. “We still continued to lecture more than we admitted to.” Others seized the opportunity to completely revamp courses, understanding that form, of necessity, would drive content.

“I’m sure some professors never left their yellowed notes,” Shearn says. “But for a lot of us, we had to move quickly and make adjustments, because the discussion might go on all day.”

“You had to start out looking at the material differently,” Cauvel says. “What is most important? What can you leave out? It was good because you had to re-think your courses. So in that sense it was really valuable.”

Still, many professors found the plan — teaching eight blocks a year with one block off — physically and emotionally exhausting. “There’s an intensity and excitement about being with the students every day, but then there is this rupture,” Cauvel says. “They go away and you don’t see them for a couple of years.”

“Faculty generally felt the Block Plan was extremely demanding, and to make it work you simply had to have time to prepare and also had to have time to maintain your professional life, which feeds the courses you teach,” Ashley says.

Efforts to lighten the teaching load led to several reductions in the number of teaching blocks; today, most faculty teach six, and have three blocks with no formal teaching assignment — “a real escape valve,” Ashley says.

Reality changed the vision in other ways. Originally intended as a holistic scheme that integrated courses with residential life and a leisure program, what Brooks still calls “The Colorado College Plan” quickly became synonymous with its defining feature, the academic block. Residential life exists now largely as its own entity; the amorphous leisure program never hit its stride.

The latter was “an attempt to answer the question of what we wanted the intellectual and cultural tone of CC to be like,” says Classics Professor Owen Cramer, who was involved with the program early on. “We wanted a college culture that wasn’t just course-taking. What were we going to do with the part of the day we’re not in classes?

“But it was already clear in the ’70s, that it was going to be very hard to sustain that tripartite vision of college life … nobody really understood the leisure program.”

Yet the academic block — the radical innovation that became synonymous with Colorado College — endures, the answer to a question put by a frustrated professor in a dive bar on a gloomy November afternoon more than a half-century ago.

Three professors walked into a bar.

They came out with an idea, which became a vision, which became a plan, and then a reality shaped by the crucial question Glenn Brooks posed: How can we do what we do better?

Give faculty 15 students and let them work. No bells; no interruptions. It was the end of what Shearn calls “the sterile classroom.” Instead, he says, “we became part of nature, talking about and moving through the experience.”