In the Before Times, Colorado College students would go to the college’s cafeteria, grab reusable plates and silverware, and serve themselves from a spread of food. At the college’s coffee shop, students could bring their own mugs instead of using disposable to-go cups.

But then the pandemic hit, and guidelines for COVID-19 safety began encouraging everyone to embrace single-use containers. At CC, pandemic safety included serving food on disposable products in the dining halls and delivering packaged meals to quarantined students.

“The waste stream that’s coming off of that has been much larger and much more concentrated,” said Director of Sustainability Ian Johnson in a recent interview with The CC COVID-19 Reporting Project. “Even just hauling the waste has become an issue just because of the concentrated loads,” he added.

As college campuses across the country try to mitigate the spread of Coronavirus by reinventing packed cafeterias as takeout locations, some worry waste may be piling up.

“Because of health reasons, everything has to be served in a to-go container. That’s just not something that can be negotiated,” said Westly Joseph ’21, the zero-waste programming and outreach intern for CC’s Office of Sustainability.

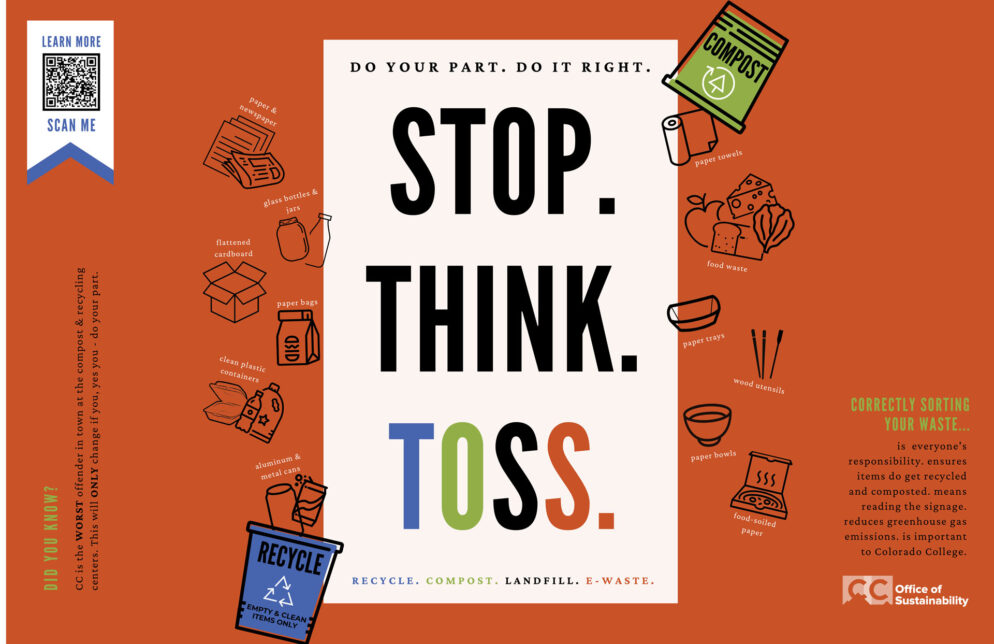

One strategy? Film a video for incoming students to watch during New Student Orientation that explains how to dispose of Bon Appétit’s most commonly used containers. The video, called “Trash Talk,” demonstrates which containers go into compost, recycling, or trash. Joseph said the Office of Sustainability also suggested that Bon Appétit [the college’s food service provider] should only give students plastic silverware with their meal if they requested it.

Still, waste overflow in the quarantined dorms proliferated. Originally, Sodexo — the hospitality company that works with CC — had employees going through the dorms to sanitize high-touch surfaces and take out trash, Joseph said, but there was so much waste they couldn’t stay on top of it.

“Then Sodexo suggested that students, when they go into their outside time, drop their trash off in the dumpsters,” Joseph told The CC COVID-19 Reporting Project. “With the help of students, that was the best option.”

This winter, the college will participate in the “Campus Race to Zero Waste,” an annual competition during which institutional participants weigh everything in the trash, recycling, and compost bins to track how much waste they produce. When the competition occurs, the Office of Sustainability will have more data on the amount of waste on campus this semester, Joseph said.

In addition to disposable containers, pandemic guidelines encourage increased ventilation capacities in buildings, which is effectively measured by the number of air changes per hour in an area. Air changes are facilitated by heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, so a necessary increase in the number of air changes lead to HVAC systems using more energy.

Because of the pandemic, CC increased air changes in buildings from about two per hour to three. “So we’re looking at roughly about a 33% increase in heating and cooling loads,” Johnson said, though he added that some of the increase is being offset by a “de-densified” campus.

During the cooling season (summer), increased airflow means that more chilled air needs to enter a room. CC uses electrical chillers that run on renewable energy. “And so while we have an increased energy profile, we don’t have an increased carbon footprint associated with that,” Johnson said. “It just means that we’re consuming more solar power.”

Conversely, the heating season (winter) uses warm air from a central heating plant that is primarily fueled by natural gas. Though natural gas produces far fewer greenhouse gases than burning coal or oil, it is still a nonrenewable energy source that produces emissions, consequently increasing CC’s carbon footprint.

Photo by Ian Johnson

In January, CC fulfilled its goal of becoming 100% carbon neutral by 2020. That means the school has a net carbon footprint of zero — the output of emissions is equal to the amount the school sequesters, or takes out of, the atmosphere.

CC sequesters emissions through carbon offsets, which are monetary investments into projects that remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it elsewhere. The increase in emissions due to more frequent air changes will probably lead to further investment into carbon offset projects, Johnson said.

CC has also seen decreased emissions in some areas. For example, fleet vehicles are not traveling as often, and the pandemic has grounded most business travel.

“Some of the fundamental shifts that happen here may permanently alter our greenhouse gas profile and what those sources are, but only time will tell,” Johnson said.

Though the concerns surrounding pandemic waste and energy are nothing to sneeze at, for Johnson and Joseph, sustainability isn’t just about the environment — it’s about improving the welfare of society in a variety of ways.

“Sustainability is not just environmentalism,” Joseph said. “It’s racial justice. It’s gender equity. It’s sustainability of having work that you can be passionate about and that you can do for the foreseeable future rather than being burnt out.There are many different aspects of sustainability, and our office acknowledges that.”

Johnson agreed, citing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as getting at a broader understanding of the word “sustainability.”

“We’re not just going to go back to business as usual,” Johnson said. “But what is a reasonable thing to start planning for, and how do we get around some of these hurdles and start doing this in a way that is more environmentally sustainable? … Sustainability is about meeting needs now and into the future.”

Original publication date: Sept. 30