By Mitchell Adams

PAONIA– Casually zooming through dimly lit tunnels deep inside a mountain housing Colorado’s last underground coal mine, John Poulos, an engineering manager at West Elk Coal Mine, blinked the headlights of a rugged pickup truck before taking a sharp turn. As Poulos routinely navigated the 7.5-mile long maze, he discussed the future of mining.

“All your true wealth comes out of the ground,” Poulos said. iPhones, agriculture equipment, cars, and batteries all require mining, Poulos said.

Poulos has been working in the mining industry for over 40 years, both in the mine and as a manager, supervising the engineering department.

He has seen changes in many aspects as two coal mines have recently shut down in the North Fork Valley, leaving around 1,000 workers jobless. Culturally, Paonia, the home of the West Elk Mine has transformed, Poulos said.

Paonia has gone from a mining and agricultural town to a place filled with “artsy-fartsy stuff,” Poulos said. “There are three juice bars and four bike shops in Paonia.”

The town’s culture isn’t the only aspect that has shifted.

John Poulos, who has worked in the mining industry for over 40 years (Whitton Feer)

“I’ve lost a number of friends that have moved away, and they will never come back,” said Kathy Welt, an environmental engineer at West Elk.

As the mines have closed, families have had to leave the valley to maintain the economic lifestyle they were used to, Welt said.

Coal mining often provides families with sustainable incomes and benefits. Coal miners at the West Elk Mine can make around 110,000 dollars including benefits annually, Welt said. When these jobs disappear, communities struggle.

“It trickles down from us,” Welt said.

In Delta County, officials are thinking about consolidating the schools of Paonia and Hotchkiss. Hospitals are struggling, as many nurses have left with their families who had previously benefited from working at one of the mines.

“Everyone is in survival mode, trying to keep our families whole here in the valley,” Welt said.

Climate experts like Amory Lovins, who spoke to reporters inside of the Rocky Mountain Institute headquarters in Basalt, are heavily pushing renewable energy sources over fossil fuels. Inadvertently, this is exacerbating the North Fork Valley’s “survival mode.”

“Markets flip quickly,” Lovins said optimistically while munching on Wheat-Thins.

Lovins is optimistic that extreme climate warming can be largely mitigated by using smart design strategies and moving towards renewable energy sources.

He finds that mainstream climate reporting doesn’t focus on conservation-minded design nearly enough. Lovins used the production of steel, which releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, as an example.

“How to not use steel doesn’t get attention like how steel can be green,” Lovins said.

Lovins also discussed the importance of minimizing the level of energy people and buildings use.

Amory Lovins shows a computer monitor charting the efficiency of his home to reporters (Whitton Feer)

Both his home and RMI’s innovation center use passive energy technology, meaning they hold heat extremely well due to insulation, and hardly need any electricity to be warm. Accompanied by solar panels, these buildings are energy net positive, meaning that they can give energy back to the grid.

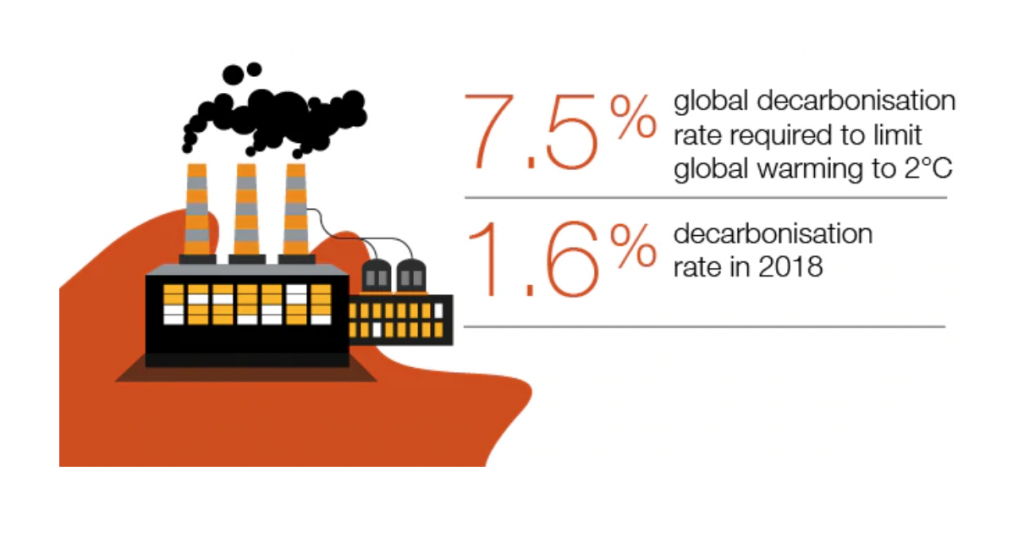

Price Waterhouse-Cooper, a major international consulting company, recently released a decarbonization index. It states that in order to limit climate warming to 2 degrees Celcius by 2100, which is a moderately positive scenario, the world needs to reduce carbon going into the atmosphere by 7.5 percent every year.

In 2018, the decarbonization rate was 1.6 percent.

Price Waterhouse Cooper’s 2019 carbon index

With this urgent decarbonization movement brought on by climate experts like Lovins, rural mining communities like the North Fork Valley will suffer as they lose their biggest economical asset, coal.

Working for the coal industry in Paonia, Welt is not sure if decarbonization changes anything.

“We believe it’s so minute,” Welt said. “They’ve shut down coal-fired power plants and we don’t believe it made a difference.”

Even with optimistic beliefs regarding the climate effects of the coal industry, Welt knows that the market is changing.

She says she has concerns for the economic future of Paonia.

“It has to be diverse,” Welt said.

Both of her sons live in the valley and have worked in the coal industry. Camden Welt has set up a ranching operation which he hopes will prove economically viable, as he moves away from the unpredictable coal industry, Kathy Welt said.

One of the proposed methods to diversify Paonia’s coal-dependent economy is using solar power to create a new industry in the valley.

Solar Forward, an initiative started by Paonia based Solar Energy International, aims to provide technical development for rural communities looking to get involved with renewable energy.

The idea was based on Paonia’s changing economic structure.

“The economic benefits of a solar market goes far beyond jobs,” said Mary Marshall, the program manager for Solar Forward.

Communities see energy independence, which correlates directly to economical independence allowing money to stay in the community, Marshall said.

If the renewable industry continues to expand, the job sector will grow as well, Marshall said.

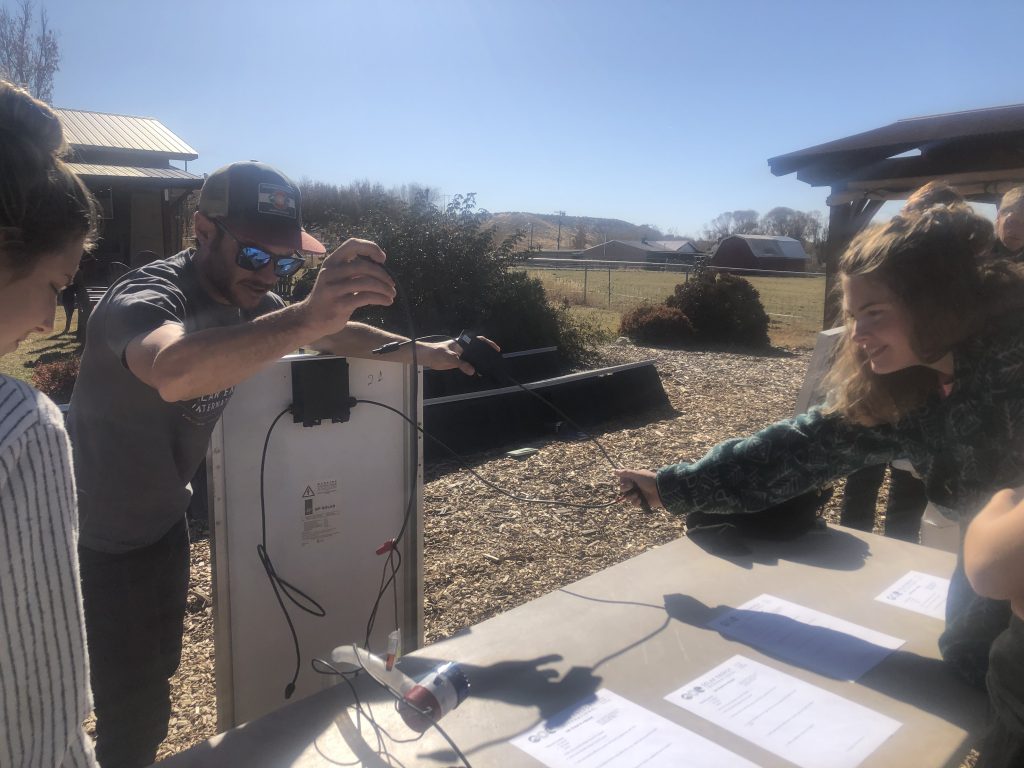

Solar Energy International, which has a solar education campus in Paonia invited reporters to tour the facility and learn about solar. Here, journalists learn how to create a water pumping circuit using solar (Johnna Geick)

Even with a potential solar industry, the future of the North Fork Valley is unknown, and a recent court decision hindering the West Elk Mine may have ramped up the uncertainty.

On November 8, a federal judge blocked the United States Interior Department’s previous approval of the West Elk Mine’s 2,000-acre expansion into the Gunnison National Forrest.

This decision could lower the already declining lifespan of the mine.

While court decisions, climate scientists, and international consulting firms collectively push to shut down all things coal, working-class people struggle to figure out what comes next.

“Pay and benefits don’t grow on trees,” Welt said. “My boys are afraid.”