When Owen Cramer went to Oberlin College in the late 1950s, he planned to pursue chemistry. Tim Fuller attended Kenyon College around the same time, ready for pre-med.

The two Chicagoans settled in, started studying, and soon found passions leading them elsewhere.

By 1965, that “elsewhere” was Colorado College. Cramer, a Homerist who could recite Latin like “a mad priest,” was hired to restart a defunct classics program. Fuller, a political philosopher with eyes only for liberal arts education, would broaden the focus of the Political Science Department.

A half century, of course, is no small chunk of time; as Cramer notes, Rome became the center of the world between 220 B.C. and 167 B.C. And over the last 50 years, he and Fuller have moved to their own exalted spots at CC. They’ve served on countless committees, including the one that created the Block Plan; hired other longtime faculty members; and helped send thousands of students into successful careers of their own.

“They are iconic, they are enduring; they anchor the college’s values and mission,” said Sandra Wong, dean of the college and dean of the faculty.

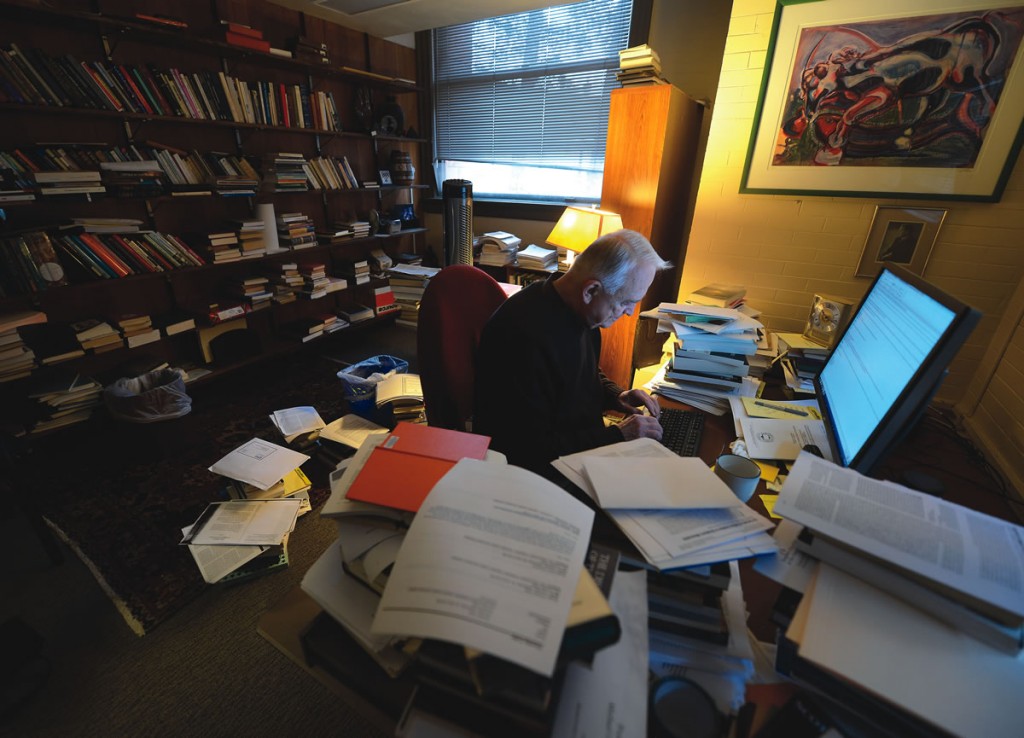

Owen Cramer, Professor of Classics

Owen Cramer spent his senior year of high school abroad, in Athens. At Oberlin College, he deepened his knowledge of Greek, studied German, “reactivated” his middle-school Latin, and even served as an emergency French teacher. After graduate studies in classics at the University of Texas at Austin, he came to Colorado College — a place he said he’d never heard of before being contacted for an interview.

Clearly, the man has no fear of educational experimentation, which made him and CC an excellent match in 1965.

At a college whose classics program had been mothballed for a decade, the 23-year-old Cramer immediately operated as his own department. He shared space with history faculty, and his first courses, in Greek and Roman history, were cross-listed.

He also tackled Latin, as Jenny Holland ’72 remembers well. Newly enrolled in 1968, she had some background in the classics — and near-certainty that they were irrelevant in the tumultuous modern era. That alone would have made her first meeting with Cramer inauspicious, but she also mistook the youthful professor for another student. No matter.

“He assigned me a book by Apuleius called ‘The Golden Ass,’ which was written in Silver Age Rome about a total Roman counterculture,” recalled Holland, who now as a music teacher strives to help young people make similar connections. “I was kind of blown away.”

It was no cursory nod to the present. Outside of class, Cramer was putting in time as a draft counselor and as a member of the El Paso County Democratic Central Committee. At the same time, he also was serving on CC’s Academic Program Committee, which sought to establish the school’s operational goals for the 1970s, and general objectives for the rest of the century.

“We were building utopia for after the war,” he said. “And the war wasn’t even over by 1974.”

But if the committee couldn’t control that, it could establish the Block Plan. Longtime CC professor Glenn Brooks would call Cramer “a steady source of fresh ideas” during that time, though Cramer probably gained more attention for an episode in which he read Homer’s “Iliad” aloud, sunup to sundown, over three days with a group of students at various campus venues.

“He’s definitely a maverick,” said fellow Classics Professor Marcia Dobson, whose presence at CC is actually another testament to just that.

In the ’70s, Cramer was eager to expand the department. To enhance his chances, he led dozens of students in independent study blocks — up to 36 at a time, he remembers — so that he could tell administrators, “I have this heavy teaching load. I need staffing relief.”

Dobson was his selection, and she turned down other offers to join Cramer at CC. She remembered, “I said to myself, ‘I could learn more from this man about classics in two years here, even if I leave after that, than I could going anyplace else in the country.’”

Of course, neither of them has gone anyplace else. They established a major in classics in the ’80s, and expanded the department with a third tenured position 20 years later.

Along the way, Cramer has helped establish, and direct, CC’s Comparative Literature program. He has chaired the Romance Languages and Spanish departments. He has sung in the Colorado College choir, contributed music criticism to local media, and served on neighborhood boards. He and his wife Becky have raised four kids.

Cramer said sometimes he and other longtime professors talk about how their careers may have unfolded at big research universities. But he has no regrets about having taken a chance on CC back in ’65, and no plans to stop teaching anytime soon.

“This,” he said, “is as good as it gets.”

Tim Fuller, Professor of Political Science

At a conference in England this fall, Paul Franco ’78 ran into Tim Fuller, his college professor from 40 years ago. They got talking about movies, and Fuller said he’d recently watched “Her” and “Ex Machina,” at his students’ recommendation.

“He said, ‘Whenever a student suggests that I watch something, I always do,’” said Franco, who’s a professor of government at Bowdoin College. “And I thought, ‘That is the secret formula for keeping in touch with students.’ … He remains ceaselessly curious about them and interested in what they have to say.”

That, Franco believes, helps explain Fuller’s youthfulness and effectiveness as a professor. And it’s evidence of what another alum, Todd Breyfogle ’88, considers Fuller’s devotion to carrying on “the conversation of mankind,” as Michael Oakeshott would phrase it.

In Fuller’s story, Oakeshott, the 20th-century British political philosopher, is a presence almost from the beginning. While researching a paper on Thomas Hobbes in his sophomore year at Kenyon College, Fuller picked up an edition of Leviathan with an introduction by Oakeshott. He devoured all 60 pages that Saturday afternoon, and said, “On Monday morning I went to the professor … I said, ‘Well, I’ve decided that I want to go to graduate school in this subject and teach it.’

“Now, did I really know what I was talking about? Probably not.”

But through his graduate career at Johns Hopkins University, nothing changed his mind. “I was interested in observing politics as the kind of dramatization of the human condition,” he said. “The place where the human condition shows itself in its most public form.”

It was at Hopkins that Fuller met longtime CC professor Glenn Brooks through a mutual acquaintance, right when Brooks and company were seeking a professor of political theory. Fuller interviewed, got the job, and moved West to the first coed undergraduate environment he had ever experienced.

As a new professor, Fuller said, he pressured himself to construct elaborate lectures “that had way more material in them than you could deliver in a 50-minute period.” Then one day in class, he looked up from his papers and saw a sea of glazed faces.

“So I put down these notes,” he remembered. “I walked out in front of the podium and I just asked them what they thought. And that changed everything.”

The changes were actually just beginning, with the Block Plan he helped create taking effect in 1970, and the college preparing for its 1974 centennial. For that latter celebration, Fuller invited Oakeshott to speak on campus, and the philosopher accepted. It started a relationship that deepened until Oakeshott died in 1990, and that Fuller has honored with extensive published work since.

Fuller wrote in depth about his Oakeshott connection for CC’s 125th anniversary memoir collection, in part to express gratitude for the opportunities the college has afforded him over the years. That concept comes up again when he talks about his turns as dean and acting president in the ’90s and 2000s, respectively.

“I never wanted to become a professional administrator,” he said, “but I was very happy to serve in those various capacities simply because I owe the college a lot.”

His bond to CC includes his wife Kalah having earned an MAT degree here, and having two daughters graduate from the college in the ’90s.

Today, Fuller said he sees no reason to stop teaching and writing, and continues to feed a passion that falls somewhere in between the two. For decades, he has held an informal “political theory discussion” group in his home, inviting any interested students in to talk about great literary works. “Sometimes I choose what we’re going to read,” he said, “sometimes they choose.”

With Tim Fuller, it would be hard to imagine it any other way.

2 Responses to 50 Years with Owen Cramer & Tim Fuller

As we would say at Georgetown, “hoya saxa!” Owen can translate.

Jim O’Donnell

ASU

Nice to read this about my cousin Owen. I see him rarely, but do stay in touch. I also saw photos on Facebook of the ceremony where he and Fuller were honored for their teaching tenure at CC. Coming from a family of educators (including his parents), Owen is just “doing what comes naturally.”

Comments are closed.