When Ellen Weir Casey earned an English degree from Colorado College in 1971, she knew she wanted to teach young children whose innocence and possibility had always touched her.

Eight years later, she found herself consumed by another desire, one that would ultimately redeem a devastating mistake and fulfill the most cherished potential of her own life: having a baby.

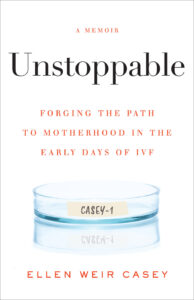

Her determination to achieve that dream made Casey the mother of Colorado’s first test-tube baby, the end of a harrowing years-long odyssey she recounts in a new memoir, “Unstoppable: Forging the Path to Motherhood in the Early Days of IVF.”

“Young women today assume in vitro (fertilization) is always an option,” says Casey, who lives in Colorado Springs. “But it wasn’t back then. There’s not a lot out there about the history of early infertility treatments, especially about the early patient’s experience. Young women need to know about the strong women who went before them, who opened the doors for them.”

“Young women today assume in vitro (fertilization) is always an option,” says Casey, who lives in Colorado Springs. “But it wasn’t back then. There’s not a lot out there about the history of early infertility treatments, especially about the early patient’s experience. Young women need to know about the strong women who went before them, who opened the doors for them.”

Casey’s saga began in 1974. Seeking an alternative to the birth control pill and trusting her doctor, she agreed to an experimental IUD.

“As smart and educated as I was, I still had the mindset of believing what a man in authority told me,” says Casey, then a graduate student at CC. Two months after the device was inserted, she sought emergency help for a high fever, cramps, and a raging infection that occluded her fallopian tubes. The IUD was removed, but the damage was done. Casey learned she was infertile five years later, as a newlywed unable to get pregnant.

She blamed herself.

“It was so important for me to be a mother,” she recalls. “And I felt like I personally had ruined my own chance to have what I wanted by taking this IUD without researching it.”

Research would consume much of the next few years. Casey became an expert in emerging reproductive technologies, poring over microfiche, reading medical journals, and logging the countless hours necessary to educate herself in the pre-Internet age.

“My research skills definitely were excellent because of CC professors having such absolutely high standards,” Casey says. “CC taught me the importance of a primary source … to always find excellence, to find the best thinker, the most innovative thinker.”

It wasn’t the first time she had benefited from the college. CC helped pay her senior year tuition after her parents divorced, leaving her suddenly cash-poor. A few years later, CC allowed Casey, who already was a working teacher, to earn a Master of Arts in Teaching by enrolling in summer liberal arts institutes without the usual additional coursework. She graduated with her MAT in 1977.

Casey’s dogged research on infertility generated early possibilities, but each ended in heartbreak. In 1979, pioneering microsurgery opened her left fallopian tube, which allowed her to conceive. But it also caused scarring, which resulted in an ectopic pregnancy that might have killed her had she not recognized the symptoms and had an emergency operation.

In 1980, Casey had laser surgery, also new at the time, to open her remaining fallopian tube — only to suffer another life-threatening complication in the form of a rapidly growing cyst six weeks later. Another emergency surgery removed the cyst and the tube — along with any chance of a natural pregnancy.

There also were failed attempts to adopt before Casey — truly unstoppable — turned to the nascent technology of IVF, which involves removing eggs from a woman’s ovaries, fertilizing them with sperm in a Petri dish, and then transferring the embryos into the woman’s uterus.

“My odds were 9% that this would work, that I would get pregnant and have a live birth,” Casey says. “It was experimental; they were still trying to figure it out.”

But Casey’s last shot turned out to be her best. In 1983, she welcomed daughter Elizabeth, Colorado’s first test-tube baby. Thirty-five years later, in 2018, Casey became a grandmother to Bennett — an extension of a dream deferred but never relinquished.