By Lili Weir

Potato farmers facing a shift to aridity in the San Luis Valley are turning to alternative agricultural practices to sustain themselves in a changing environment.

“We’re committed to making it work,” Rio Grande Water Conservation District general manager Cleave Simpson said in a recent interview.

A fourth generation farmer, Simpson said he sees fundamental problems resulting from over-pumping underground aquifers. This draw-down of the aquifers, combined with the decreasing snowpacks along the Rio Grande River headwaters, are shrinking the overall amount water available and drying out the valley.

“Our demand for water exceeds our supply,” Simpson said.

To survive in this increasingly arid environment, potato farmers are forming subdistricts to impose aquifer pumping fees, planting vegetation in rotating fallow fields to restore soil health, and using crops that require less water with help from agricultural scientists.

The climatological data surrounding the viability of continued farming in the Southwest appears less optimistic than many of the farmers seem to want to acknowledge.

“I don’t think about it,” third generation potato farmer Sheldon Rockey said.

In spite of some farmers denial, the shift to aridity in the San Luis Valley is apparent and unavoidable, Simpson said.

Scientists have projected that the Southwestern United States will become increasingly uninhabitable, let alone fertile enough to sustain agriculture.

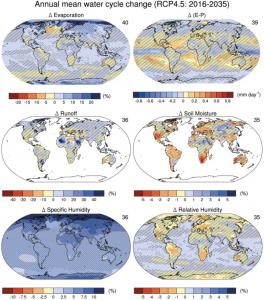

The levels of dryness (see relative humidity, evaporation minus precipitation, and soil moisture below) are projected to change the Southwest into a more parched environment, according to data put forth by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

(AR5 Chapter 11 Near Term Climate Change, Figure 11.4)

As the valley becomes more arid, farmers turn to tried and true well technology, to pump even more water from aquifers, and subsidize the amount of water they need for their farms that they are no longer getting from snowpack runoff.

The environmental and economic implications of over pumping aquifers could be ruinous to agricultural industry in the valley.

“If we do nothing we will pump our aquifer to the bottom,” Simpson said.

Farmers have organized themselves into subdistricts to enforce fees on the water being pumped from these aquifer wells, and use the money generated from this tax to incentivize fallow field programs valley wide. Although the price per cubic foot of water continues to increase annually because of increased aridity, Simpson maintains that these subdistricts are essential in moving towards a water balance.

Farmers are increasingly turning to scientists for more advice on how to maximize the efficiency of their farms in terms of water and cost, said potato researcher Samuel Essah at the San Luis Valley Research Center.

One effective way of doing this is to encourage farmers to move away from crops that require a lot of water to more water conscious plants. This includes shifting away from producing barley and alfalfa, and using more varieties of potatoes and quinoa, Essah said.

Another practice that many farmers are starting to use includes a return to crop rotation and seeding out of use fields with sixteen different types of plants that don’t require irrigation and sequester nitrogen. Doing this increases the soil quality of the land, and actually allows farmers to maximize their production on fewer acres which cuts the cost of water significantly.

“By having this kind of rotation we’ve cut our water usage in half,” said Rockey.

“The bottom line is economics,” said Essah, and implementing these practices not only benefits the farmers pocketbooks, but also renews the soil which leads to less erosion and lessens the amount of water being mined from the aquifers.

Even in spite of the increasingly insecure water supply in the valley, locals remain optimistic about their ability to withstand these changes thanks to these new practices.

“Our plan is to be here…. I believe it’s going to work,” Rockey said.