By Mitchell Adams

SALIDA— Proudly gazing through a window at the five fourteen thousand-foot peaks he can see from his log-cabin-chic living room, homeowner Jerry Mallett explained why he chose to build his dream home in a forest fire zone.

“My wife wanted a view,” Mallett said with a grin. “We had to roll the dice.”

The risk of their gamble was evident on the morning of October 2, when Mallett and his wife Nancy got a call from the sheriff at 2 A.M. advising them to evacuate because the Decker Mountain fire was burning within a mile of their home.

Mallett took it seriously and knocked on his neighbor’s doors, making sure they were awake before he headed down into the town of Salida around 5:30 in the morning.

“The whole mountain was on fire,” he said.

Mallett’s home is perched on the side of Methodist Mountain, overlooking the town of Salida in addition to the snow-capped peaks. He has thinned out most of the trees surrounding his house. But one tree stands close, with snowy branches hanging over his wooden deck. Mallett acknowledged the risk of the tree during a recent conversation with federal forest officials in his living room.

After a week, the Malletts were able to return to their homes. Nobody in the area was hurt during the Decker fire, which burned 8,959 acres before firefighters put it out, according to the federal incident report.

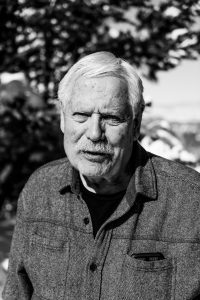

Jerry Mallett lives in a house near the Decker fire. He was evacuated for about a week. (Whitton Feer)

In Colorado, forest fires are becoming more of a threat to people who insist on living in the woods, federal officials said.

As the climate becomes increasingly arid, more of the low-level brush is dry and primed to be fire-fuel. Also, warmer winters, due to climate change, are allowing more tree-killing Pine Beetles to survive than usual, which increases the amount of dry, dead timber.

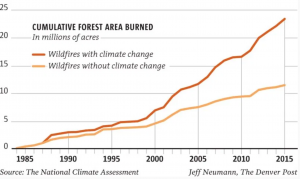

According to the National Climate Assesment, Climate Change has a direct effect on the number of forest fires, in Colorado, and all over the country.

National Climate Assesment chart showing a projection of wildfires if the climate was not warming

The authorities in Chaffee County, where Mallett lives, have set no rules on where someone can build a house in relation to forest fire zones, said Mallett, a former county commissioner.

When he built his house in 2000, he knew the property was in a potential burn zone, Mallett said. Building here is a “choice and gamble” that people are still taking, even with the increased fire risks, he said.

Mallett knows a lawyer who moved in from Mississippi and built a house fairly far up the mountain. She wanted a secluded home with a view.

“Anyone who moves up here is opportunistic,” said Mike Rosso, one of Mallett’s neighbors, who runs the Colorado Central Magazine out of Salida.

Mallett woke up Rosso by pounding on his door. Russo’s first worry was about his cat escaping the house. From there, he grabbed his musical instruments, computers, cash, and his cats.

“I was sharp and focused,” Rosso said.

Even after these smoke-filled horrors, plenty of people are developing homes in the area.

Winding roads snaking up the side of the mountain connect secluded, modern, pastel-colored houses. All of the homes feature privacy and a spectacular view.

A housing development called Boothill was also evacuated during the Decker fire. Boothill has a promotional site touting, “well-treed lots with mature Pinon Pines for privacy and interest,” and the land’s close proximity to trails. The site makes no mention that the subdivision is located in a forest fire risk zone.

As people continue moving into these dangerous areas, fire services have to protect them.

“For me, my job is to protect my people, if your home is there or if you’re a visitor to the forest,” said Terry Krasko, a staff officer for the United States Forrest Service, who was assigned to the Decker fire.

Tom Kenney, a helicopter-tech leader for the Forest Service usually attacks forest fires when they’re small. On this job, he said he was more concerned about protecting the people.

Kenney outlined how the forest fire season is becoming longer due to the changing climate. The season now stretches from April into November, much after the seasonal workers, often students, return home. This, along with houses built in burn zones, burdens the Forest Service.

“We are looking to have a higher level of permanent staff,” Kenney said. “It would be nice.”

Burn zone from the Decker fire (Whitton Feer)