By Mitchell Adams

ALAMOSA— For farmers in the San Luis Valley, farming is more than work. It is their life.

“It’s what we do,” said Cleave Simpson, the general manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District. “People have been here for eight to nine generations doing the same thing.”

Agriculture is the largest industry in the valley, and it has been for hundreds of years. Simpson is a fourth-generation farmer, and his son is planning on farming as well.

But farmers in the valley may not be able to continue.

Over-pumping of groundwater and a climate shift to aridity, often bringing less snowpack are reducing water levels in the valley, a recent series of interviews determined.

In the past, the valley’s underground water contained in aquifers made farming a breeze, as farmers would suck up water from the ground for their crops when surface water was insufficient, or if they didn’t have rights to divert river water.

Today, water supply is a source of tension. Some farmers with wells barely acknowledge that their pumping can affect the entire water system.

Farmers who depend on diverting water from rivers, such as the headwaters of the Rio Grande River struggle due to decreasing flows over the last two decades. Water levels, both in rivers, and aquifers are steadily declining, Simpon said.

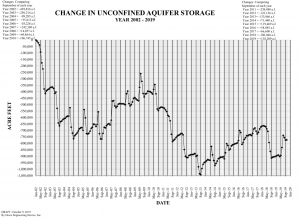

A Rio Grande Water Conservation District chart showing the decreasing levels of water in the unconfined aquifer

“We are seeing a shift to aridity,” Simpson said.

Farmers in the valley are fighting to survive in this new arid climate.

They have taken initiative to solve the water issue because it will determine whether agriculture is sustainable. Farmers have formed subdistricts, and put self-imposed fees on groundwater, currently at $90 per acre-foot pumped (1 acre-foot equals 325,851 gallons), Simpson said.

Farmers can also reduce the amount of land they irrigate. Simpson said that this may be the most efficient way to ensure balance and sustainable water use.

To cut back on land use, farmers can take advantage of the federal government’s long-standing program that compensates farmers for not farming.

The Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program pays farmers to idle parts of their land for 15 years. Even though this income may exceed what farmers could earn growing crops, the program has not been popular in the valley, Simpson said.

“People don’t want to deal with the U.S. government,” he said.

He cited rigidity of the 15-year contracts, and the lack of freedom to rotate which parts of a farm are idled as other reasons the program is not successful.

Farmers participating in their newly formed local subdistricts are using some of their water-fee revenue to run their own friendlier custom version of the federal land idling program.

This version gives farmers greater flexibility to determine their own rotation of idled land.

“We’re scrambling,” Simpson said.

In this water struggle, stakes are high, said Sheldon Rockey, a co-owner of Rockey Potato Farm in Center.

If farmers aren’t able to reduce their pumping of groundwater and snowfall in the mountains is too sporadic to rejuvenate water supply, Colorado’s state engineer has threatened to come into the valley and shut off wells.

Rockey said he dreads this state-level intervention and worries that the state engineer essentially would, “throw darts on a map” to determine which farms could survive. Farmers want to solve the problem themselves because the state engineer doesn’t know the cultural makeup of the valley, Rockey said.

“I’m concerned about the valley,” Rockey said.

Farm equipment on the Rockey Potato Farm (Whitton Feer)

Even in the face of intensifying water challenges, the bulk of farmers are still producing. In some cases, farmers are continuing to pump as if nothing has changed.

But about 60 percent of farmers are following the advice of experts on how to use less water growing potatoes, said Samuel Essah, a state-backed potato researcher at Colorado State University’s San Luis Valley Research Center.

“Farming is the kind of business where you need to like it,” Essah said.

If farmers weren’t so passionate about their work, the natural eco-systems in the valley might fare better, Essah said.

“Farming’s in our blood,” said Riley Kern, a 22-year-old farmhand who grew up in the valley.

Reilly Kern, 22, in front of a pile of fingerling potatoes (Whitton Feer)

Kern is one of three full-time employees at the Rockey potato farm. The other two, brothers Sheldon and Brendon Rockey, represent third-generation potato farmers.

“We want to be here,” Rockey said, optimistically looking ahead to the future, “so our girls have an opportunity to farm.”