Come to the first State of the Rockies Speaker Series events tonight at 7pm in the Cornerstone Arts building on the CC campus! Jonathan Waterman and Pete McBride, co-authors of The Colorado River Basin: Flowing Through Conflict will be showing images from the recently published book and covering the issues of the Colorado River Basin. This first speakers series event will lay the foundation for the rest of the series titled: The Colorado River Basin: Agenda for Use, Restoration, and Sustainability for the Next Generation.

The State of the Rockies Project Speakers Series kicks off tomorrow night @ 7pm!

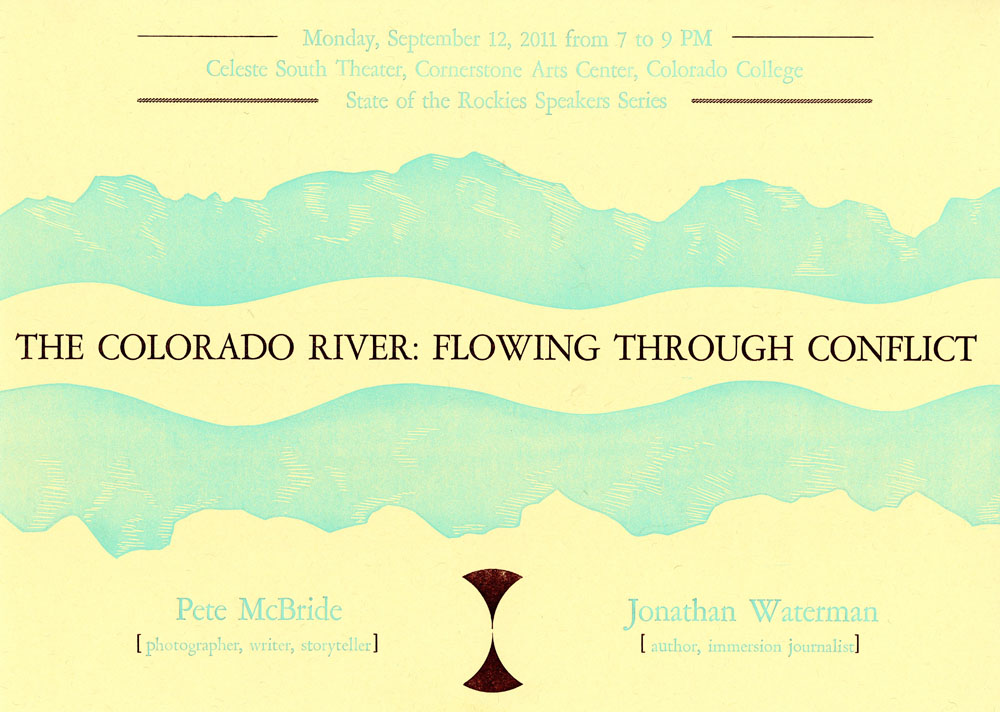

Join us tomorrow night, Monday 9/12, at 7 pm for the first State of the Rockies Project Speakers Series event of the year in the Celeste South Theater in the Cornerstone Arts building on the Colorado College campus. Jonathan Waterman and Pete McBride will be presenting on their recently co-authored book The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict and covering the contentious issues of the Colorado River Basin. This first event will lay the foundation for the rest of the Rockies Project Speakers Series: The Colorado River Basin- Agenda for Use, Restoration, and Sustainability for the Next Generation.

The first State of the Rockies Speaker Series event is just a few days away!

Come to the Celeste South Theater in the Cornerstone Arts building on Monday September 12th at 7pm to see Jonathan Waterman and Pete McBride kick off this year’s Sate of the Rockies Project Speakers Series. Jon and Pete will be covering issues of the Colorado River Basin and showing content from their recently co-authored book The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict. This first event will lay the foundation for the rest of the year’s Speaker Series titled The Colorado River Basin: Agenda for Use, Restoration, and Sustainability for the Next Generation.

Colorado College’s new President Jill Tiefenthaler blogs about the Rockies Project

Check out CC’s new President Jill Tiefenthaler’s blog and what she has to say to say about the State of the Rockies Project, this year’s Save the Colorado River Basin banner photo contest, and our field researcher Will Stauffer-Norris’ journey down the length of the Colorado River this fall: http://blog.coloradocollege.edu/president/

The first State of the Rockies Speakers Series event is quickly approaching!

The first State of the Rockies Speakers Series event is scheduled for 7pm September 12th, 2011. Jonathan Waterman and Peter McBride, co-authors of the recently published book The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict, will present their insights on the Colorado River along with some of the incredible images from their book. Check out Peter and Jon’s websites at: http://www.petemcbride.com/ and http://jonathanwaterman.com/. The talk will be held in the Celeste Theater in the the Cornerstone Arts Building on the Colorado College campus in Colorado Springs, CO at 7pm on 9/12/2011. Take a look at the rest of the speakers we’ve scheduled for the year here at: http://www2.coloradocollege.edu/StateoftheRockies/201112 Monthly Speakers/2011-12 Rockies talks and Conference announcement.pdf

State of the Rockies Research Trip Videos

We’ve finally put together the last of our footage from the 7/10-7/24 research trip and posted it to our YouTube channel. Click here to go to the channel. The four videos follow our trip throughout the Colorado River Basin and cover important stops such as:

-The Black Canyon of the Gunnison

-Moab, UT and Canyonlands NP

-Glen Canyon Dam

-Lees Ferry

-Las Vegas, NV

-Imperial Irrigation District, California

-Mexico and the Cienega de Santa Clara

-Yuma, AZ

Also check out Will Stauffer-Norris’ Source to Sea Preview and stay tuned for updates regarding Will’s journey this fall.

Day 14: South Rim of the Grand Canyon and the Navajo Reservation

After meeting with BLM officials in Lake Havasu City on Friday morning the Rockies Research Team began the trek back to Colorado Springs. Our destination for that evening was the South Rim of the Grand Canyon and the campground there. Rising in elevation out of the desert, we quickly found ourselves back in the Kaibab National Forest that we had visited a week earlier, except across the Canyon on the North Rim. Passing into the National Park we found that the South Rim was truly the tourist destination in the Park rather than the more remote North Rim. Throngs of visitors walked along the fenced pathways of the rim peering over the edge as various languages from around the world were heard. We progressed over to the Mather Campground for the night, which seemed more of a small tent city than the traditional campground full of cars and trailers with license plates from across the country. We set up for the night and began to reminisce on the long journey behind us, and excitedly anticipate the long haul ahead of us back to CC.

The next morning was another early one as we had to cross the rest of Arizona to reach the Navajo Reservation to meet with officials regarding tribal water management and the greater topic of Native American water rights. In Ft. Defiance, AZ we met with two members of the Navajo Nation. Bidtah Becker is an attorney with the Navajo Department of Justice and Jason John is a hydrologist with the Navajo Department of Water Resources. The Navajo Nation spans across Arizona, Utah and New Mexico, creating myriad jurisdictional issues (made worse by allotment: see Blood Struggle by Charles Wilkinson for more information) Since Arizona and New Mexico do not have water courts like we do in Colorado, the process for quantifying the Native American water rights can be long, arduous and politically-driven. The Navajo Nation and the State of New Mexico recently came to an agreement to quantify the Navajo water rights in the Upper Colorado River Basin in New Mexico (San Juan River)—a process largely driven by Senator Bingaman (D-N.M.). The Navajo are still pursuing the quantification of their rights in other basins and States.

Bidtah stated that the greatest threat to the Navajo Nation is poverty. Though the Navajo have extensive coal deposits, they are not connected to major rail lines, thereby limiting the market of the coal. Without the money to build infrastructure or fight expensive legal battles over water rights, the Navajo Nation faces an uncertain future when it comes to water and by extension, their economy.

After the meeting we started our last push towards home heading north through Farmington, NM and up into Colorado crossing the San Luis Valley and finally reaching the Front Range. Arriving at 1:30AM we were home after our long tour of the Colorado River Basin.

Our research for the summer was undoubtedly greatly enhanced by our travels throughout the basin; while research in the lab can open one to the issues of the region, merely staying within the confines of books and reports limits the perspectives to which you are introduced. Getting out into the basin and meeting with the stakeholders whose everyday lives are affected by the Colorado River brought a new dimension to this summer’s project. Whether it be witnessing the flows of the Gunnison through the Black Canyon (flows that are now protected) or the conservation efforts underway in Las Vegas, or engaging with the farmer committed to feeding people in the U.S. and around the world, or meeting with those whose voices haven’t traditionally been heard in the calculus of Colorado River water, we gained new perspectives regarding the multitude of issues facing the Basin. Now we must compile all of the data and research recorded during our trip, and with recognition of these new perspectives begin to work on our annual Report Card. With 3 weeks of summer research left we certainly have a tall task, but nothing that we can’t accomplish.

Days 12 and 13: Yuma, Wellton, and Lake Havasu City

Thursday, July 21st

After our 14-hour workday in Mexico, we were all ready to catch up on sleep once we arrived in Yuma, Arizona. The next morning we had another early wake-up in order to get to our meeting at the Yuma Desalinization Plant, the world’s largest reverse osmosis system. The plant was completed in 1992 to treat the saline return flows from the Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation District. Water treated by the desalting plant would theoretically be used as part of the water delivery to Mexico. I say ‘theoretically’ because, with the exception of two test runs, the plant has been sitting idle since its completion in 1992. The Bureau of Reclamation considers the plant a potential tool for extending the water supply. If the plant were to be operated in the future, it could be done at 1/3, 2/3 or full capacity; during the pilot run it was operated at 1/3 capacity. It is impossible to know what capacity it might run at in the future because of the many factors involved, such as the extremity of the current drought and the ability to deliver brackish water to the Cienega de Santa Clara.

As mentioned in the previous day’s blog post on Mexico, 90% of the Cienega de Santa Clara wetland is sustained by the highly saline drainage water from the Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation District- the same water that would be sent to the desalting plant. Minute 316 was created through binational collaboration in an attempt to address this obstacle. The minute states that the US, Mexico, and NGOs such as Pronatura would each designate 10,000 af (for a total of 30,000 af) to the bypass drain for the Cienega de Santa Clara wetland, if needed.

Additionally, during the 1960’s the quality of water being delivered to Mexico became so poor that Mexico filed a formal complaint, leading to Minute No. 242, which holds the US responsible for delivering water that is no more than 145 parts per million greater than the salinity levels at the last water quality checkpoint in the US (Imperial Dam). These levels are monitored daily, and the US has never failed to meet the requirement.

We picked up and drove to the Wellton-Mohawk irrigation district (WMIDD) in Wellton, Arizona after our Yuma morning, to meet with Ken Baughman of WMIDD and to get a tour of the region. The Wellton agricultural land area is smaller than that irrigated by the Imperial Irrigation District, only about 65,000 acres, to which the WMIDD diverts about 450,000 acre-feet per year. Of this, about 140,000 af are returned, and actually flow down through Mexico, creating the Cienega de Santa Clara wetlands, making Wellton’s consumptive use closer to 310,000 af.

While quiet at first, Baughman and his fellow WMIDD Water Master, Kurt, turned out to be great resources who offered us both the farming perspective and the reality of the situation down in Wellton. Baughman told us that back before the railroad came through this area of Arizona in 1870, the region was filled with small wells, and outsiders referred to it as “that little well-town”; the name stuck, hence “Wellton.”

Wellton-Mohawk has the largest cattle feed yard west of the Mississippi River (150,000 head), and produces crops such as iceberg lettuce (this is where the US gets winter lettuce from), cotton, wheat, sudan grass, and lots of little seed crops. It also has one of the oldest water rights in the country, meaning that projected future shortages will be delayed in impacting the region. The WMIDD is currently able to divert 4 af/yr to farmers in their district, enough to grow successful crops.

After meeting at the WMIDD headquarters, where they also handle power distribution, we learned a bit about how the district is structured by taking a driving tour of the region. We saw how water coming from Imperial Dam to the west in California is actually pumped uphill by massive pumping plants built in the early 1950s, in order to irrigate the higher-ground acreage. These pumping plants, while not the most efficient because of their age, are quite sturdy and have been very successful at keeping the region irrigated.

Our tour took us to various fields, irrigation canals, smaller pumping stations, and finally ended with a newly-introduced crop in the region, the olive tree. The climate here, while incredibly hot in the summer, is such that it’s capable of supporting a wide variety of crops, as we saw. When asked, Baughman admitted that farming in this kind of desert seems to be a little crazy due to how little water is around, yet it also seems to work.

After saying our goodbyes to our two fabulous tour guides, we took off for Lake Havasu City that evening, about three hours north. Here, we would speak with Myron McCoy, the outdoor recreation planner for the Bureau of Land Management, to get his perspective on recreation in one of the country’s most popular vacation destinations. With 10 million visitors every year, Myron has a thorough understanding of recreation in the area, as well as the impact of recreation on the environment. Boating is by far the most common form of recreation on Lake Havasu, however visitors also enjoy a variety of other outdoor adventures such as hiking, biking, camping, wildlife viewing, hunting/fishing, and off-roading.

Friday, July 22

On Friday morning, Myron spoke to us about the impact that population and recreation growth in the area has on the natural environment. The proliferation of new trails and the increasing number of off-road vehicles has proven to have a huge environmental footprint throughout recent years. However, with fewer visitors due to the downturn of the economy in recent years, Myron has witnessed a rejuvenation of much of the natural environment. There has been a decrease in trash pollution, fewer vehicles creating new off-road trails, and fewer environmental problems associated with dust.

One environmental problem that has not improved in recent years is the challenge of invasive species. There were a host of pamphlets in the BLM office educating visitors on the measures that they need to take to avoid spreading nuisance species such as the quagga mussel, a nonnative invasive species that has colonized throughout the entire Colorado River.

At the finish of the meeting, it was time to begin the long trip home. With only one meeting on Saturday, we were nearing the end of our odyssey.

Day 11: Mexico and the Colorado River Delta

We exited the exquisite Best Western John Jay Inn in Calexico, CA at 4:40am, just early enough for the previous day’s high of 113ºF to drop to a balmy 95ºF. In the refreshingly ‘cool’ air we departed from the Imperial Valley and headed out to visit our neighbors to the South in Mexico.

At the border crossing in Algodones we met up with our guide for the day, Osvel Hinojosa-Huerta, and his posse of environmentalist cohorts. Osvel, a long-time member of ProNatura, provided us with a wealth of information from the moment we met him. He explained that ProNatura was not only the largest but also the oldest non-profit environmental organization in the country of Mexico, now going on its fourteenth year. Their main objectives are the restoration of the delta area, the education of the public, involvement in public policy, and the purchasing of water rights from the government to put to environmental uses.

After brief introductions we began our daylong tour of the Mexican Colorado River Delta Region. We began our journey at the Morelos Dam, the only significant structure along the River in Mexico. The Morelos Dam, unlike the Hoover, and Glen Canyon Dam’s of the United States is only a diversion structure. Mexico itself has no storage capacity for it’s allotted 1.5 million-acre feet it receives annually from the United States. Of the 1.5 million acre feet Mexico is entitled to, 90% is delivered through Morelos Dam (the other 10% is delivered via the southern boundary delivery, and unlike the main delivery is not subject to salinity regulations). As a result, all of the flows into Mexico are immediately redirected and put to beneficial use either by municipalities such as Tijuana, or by agricultural water rights holders. The Dam was impressive in that through such diversions it realistically marks the end of the original Colorado River. On one side you see the dry riverbed where water once flowed to the sea, and on the other the recently built canal system that takes water away to where it is needed most. Osvel was quick to mention that any flooding events will result in a release from the dam allowing for the flooding of the traditional riverbed. These events, which occur no more than four to five times a year, constitute the only water that this part of the river will ever see.

Our tour of the Dam was followed by a short drive to the Welton-Mohawk drainage Canal, also referred to as the Mode Canal. The waters passing through this canal system are the made up exclusively of agricultural drainage/wastewater produced by the Welton-Mohawk Irrigation District in Welton, AZ. This water, too saline (typically in the range of 2,500 ppm) and sediment-filled to be productively used in Mexico, drains directly into the Cienega de Santa Clara, an “artificial” wetland because the water is identified as too saline to meet treaty requirements under minute 242. This water is not counted as part of the United State’s delivery to Mexico. At this same stop we were able to walk down into the old Colorado riverbed, now resembling a beach more than a river. As stated before, water no longer flows down this stretch of the river. This did provide an opportunity however, to reflect on what this region must have looked like in centuries past. One could easily envision the prolific riparian environment that once thrived here.

A somber look at what has become was quickly transformed into the realization of what could be at our next stop, Laguna Grande. Laguna Grande is part of a wider conservation, restoration, and education effort currently being pursued by Pronatura and the Sonora Institute in Mexico. The wetlands area land was gained as a concession from the government after the involved groups demonstrated public interest. Water for the land was secured through the collective purchase of water rights by all entities involved in the project. This project is not only providing for the future success of plant and animal species in the area but is being used as a way to open the eyes of the public to the environmental degradation going on in the area.

I have to take this time to remark on the unbelievable heat our group experienced all day long. If I was to exclude this remark you, as the reader would in no way be able to share this amazing experience with us. 115ºF is unlike anything you have ever felt, there was not one person not sweating through his/her shirt by midday. Marco, if you’re reading this blog, these comments are directed at you.

After devouring some of the most delicious fish tacos I have ever had the pleasure of ingesting, we made our way to the last stop on our trip, the Cienega de Santa Clara. The drive into the Cienega is unlike anything most of us have ever seen. It involves a drive through the Colorado River Delta, or at least what is left of it, a barren wasteland unfit for inhabitation by anything save a few strands of hearty and resilient grass. Without the historic flooding events and the natural flow of the river the delta has been transformed from a vibrant wetland to one of the driest places around. Eventually, we arrived at a lush and thriving “desert oasis”. The Cienaga as noted before, was created following the passage of IBWC minute 242, implementing salinity requirements on U.S. water deliveries to Mexico. The wastewater from Welton-Mohawk was so saline that its reintroduction to the Colorado River raised levels to a point where agricultural production was impossible. As a result, a canal was created to deposit the water in the delta area. The water slowly collected over the years and created what is today 14,000 acres of wetlands, now home to 250 bird species, numerous species of fish, and the Yuma Clapperail a protected species in both the United States in Mexico. We were lucky enough to be taken on an hour-long boat tour of the Cienega where we witnessed first hand its incredible biodiversity. We even made friends with a curious pelican whom proved brave enough to swim up to our boat.

After a long, productive, and very fun day, our group, for the first time on the trip, turned North and made its way to Yuma for a little rest and reprieve.

by, Warren King

State of the Rockies Researcher

Day 9: The Imperial Valley

Another early morning start took us south. We followed the Colorado River (now essentially a series of reservoirs) south, briefly stopping at Parker Dam (Lake Havasu). After the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams, Parker was not terribly impressive, though the reservoir it created is still enjoyed by large multitudes of people every year. We will be back in Lake Havasu City on Friday, and will meet with the BLM regarding the recreation in the area.

We reached Imperial, CA in the afternoon (passing bank that said it was 118 degrees Fahrenheit) and met with Vince Brooks from the Imperial Irrigation District (IID). The Imperial Valley lies west of Arizona between Mexico and the Salton Sea. The 45 (North-South) x 30 (East-West) mile area has 475,000 acres of non-stop farming. With 3.1 million acre-feet (maf) of Colorado River water—approximately 70% of California’s 4.4 maf annual apportionment—the Imperial Valley total commodity value in 2009 was almost 1.5 billion dollars.

East Highline Canal

Vince took us to East Highline Canal, one of three main arteries in the IID that come off of the All-American Canal. Looking across the valley we could see alfalfa, sudan grass, wheat, and plots being prepared for broccoli and lettuce. Much of the garden vegetables that we enjoy during the winter come from the Imperial Valley or nearby Yuma and Wellton-Mowhawk Irrigation District (where we will go on Thursday). The IID holds water rights in trust for the growers, which both gives IID greater political clout and inhibits individual growers from selling water to other users (particularly the Metropolitan Water District of Los Angeles.

Imperial Dam

The All-American Canal—constructed in the 1930’s—begins at the Imperial Dam, diverting water to both the Coachella Valley Water District and the IID. The Imperial Dam is a diversion dam, meaning that it does not have storage capacity and, instead, diverts water into canals. There are large desilting pools, designed to removed silt (sediment) from the water before diverting the water into the canals that feed Arizona and California farmland.

On the Border

We had a fun little experience with the U.S. Border Patrol, as a car came after us when we visited Brock Reservoir. They were concerned regarding the large white IID van we were travelling in. The Border Patrol agents briefly spoke with Vince Brooks and then we were on our way. During construction along the border, enterprising persons made a white van look like one from the construction contractor then snuck several people across the border.

Initinitally thinking that the border fence was a riduclous proposition, Vince remarked that before the fence was constructed they had had many problems with people both drowning in the All-American Canal and farm equipment being stolen. Since the installation of the fence (and with booms installed across the canal), both occurances have drastically decreased.

We had a late dinner with Vince in Imperial then travelled on to a Best Western in Calexico, only a few miles from the border. Even though agriculture often gets a bad rap when it comes to water use, we have to remember that our produce and meat does not come from grocery stores: it comes from farms and ranches. As Vince said, agriculture is “a national resource we should protect.”

By Ben Taber, State of the Rockies Project Researcher